American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet Publication

Version 050510KB

A BRIEF HISTORY OF

THE

ATCHISON, TOPEKA,

AND SANTA FE RAILROAD,

THE “ROUTE 66”

RAILROAD IN ARIZONA

AND THEIR FAMOUS CALENDARS

By

Kathy Block

March, 1951 ad in

National Geographic Magazine

This write-up deals only briefly with

the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad line in Northern Arizona, the

“Route 66” railroad, though there were other railroad branches to other areas

of Arizona.

The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe

Railroad had its origins with the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, which was

chartered by Congress on July 27, 1866, to build a railway from Springfield,

Missouri across the Indian Territory to the Colorado River and from there to

San Diego. Its major asset was a federal

land grant of a 200 foot right-of-way along the alignment of the future

railroad and 20 odd-numbered sections of land per mile on each side of the

tracks across New Mexico and Arizona Territories. The alignment roughly

followed the 35th parallel, which runs between the east-west borders

between the top one/third and bottom two/thirds of the Territories. This is close to the alignment chosen for

historic Route 66 when it was created in 1926.

The Atlantic and Pacific was bankrupt

in 1876, having completed only 351 miles of track in Missouri and Indian

Territory. The Atchison and Topeka Company, which had its origins seven years

before the Atlantic and Pacific charter was granted, had begun in 1859 with a

charter from the Kansas legislature to build a railroad from the Northeast

corner of Kansas thru nearby Atchison and end in Topeka – a distance of less

than 100 miles. Colonel Cyrus K. Holiday- a farmer, land speculator, and

lawyer- met with a dozen other men in a law office in Atchison, Kansas and

formally organized the Atchison and Topeka Railroad. Then, March 3, 1863,

President Lincoln signed legislation giving a 3 million acre land grant for a

railroad extending from Atchison across Kansas to its western border in the

direction of Fort Union and Santa Fe. The name was changed to the “Atchison,

Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad.” The line was completed to the Colorado border by

the end of 1872, By February, 1880, tracks reached Santa Fe.

But, that charter extended no further

west than Albuquerque. In November, 1879, though, the A, T, & S.F.

purchased a half interest in the Atlantic and Pacific and used its

charter to extend the line thru the rest of New Mexico and Arizona under the

Atlantic and Pacific name!

The Arizona alignment was surveyed by

a Lewis Kingman in 1880, with a survey team of 20 men and 5 wagons. The line

was plotted between Rio Puerco in New Mexico to Holbrook, Arizona. Then, they

followed the Little Colorado River to Sunset Crossing in Brigham City (a fort

built by Mormons in 1876, now within Winslow City limits). The crew skipped the

middle part of alignment across Arizona's high country until summer 1881.

Construction began new Albuquerque in

summer 1880. The first rail put down in Arizona was a two and one/half mile

segment in Querino Canyon, just west of present-day Houck. The company

contracted with local construction firms to clear and grade portions of the

line, do some bridge and tunnel work, and provide materials. By summer 1881

more than 2,000 men were working in Northern Arizona, preparing the way for the

rails. These workers included groups of Mormons organized by John W. Young, son

of Bigham Young. The A & P employed almost anyone they could find to work.

Rural Arizona had a very limited labor pool, including local Hispanics, Apaches,

and Navajos. They also recruited recent emigrants from the mid-west, resulting

in crews with a large Irish contingent. (Footnote 1.)

Charles S. Gleed, whose name was given

to a settlement along the railroad, wrote an article for The Cosmopolitan,

February, 1893. (Footnote 2.) In it he mentions fears

of great financiers who said that money invested in “the great American desert”

would never come back. Eventually, with Col. Holiday as the originator of the

enterprise, “the right man came and the locomotive and the Pullman car drove

out the ox team, the covered wagon, and the desolate trail became the highway

of nations.”

At the time of the article, there were

9,298 miles of track, nearly all single track, a mileage equal to one/third of

the distance around the Earth, and one/sixteenth that of the United States. In

Arizona, there were 490 miles.

Altitudes within Arizona included

7,257 feet at Continental Divide in Arizona, 4,848 feet at Winslow, 6,886 feet

at Flagstaff.

Track laying at a rate of a mile a day

was often achieved. Most of the lines of the system preceded settlements, “not

to say civilization”, passing thru new country, too remote for substantial

settlement without the railroad coming.

The people of New Mexico and Arizona were nearly all Spanish Americans,

except the Indians.

The Arizona line reached the mining

and grazing regions of Northern Arizona by an east to west line from New Mexico

to California at Needles.

Settlements began along the railroad

line, often using the checkerboard sections granted to the railroad. The tracks

began in Houck in the summer of 1880 and reached Kingman in March,1883. The bridge over the Colorado

River was completed and the line reached Needles, California in August 1883.

Passenger and freight stations began to be erected along the railroad. Nine of

the 50 stations in Arizona were along Route 66.

Six “Harvey Houses” and hotels sprang

up to serve passengers and crews, along this route. The famous El Tovar Harvey

House, built in 1905 by the Santa Fe Railroad still stands at the Grand Canyon

and is owned by the National Park Service as well as the Bright Angel Lodge,

built for the ATSF Railroad in 1935, under famed female architect Mary Colter.

It still exists also under National Park Service management.

Some of these settlements and stations

along the Northern Arizona route near Route 66 are of interest to the APCRP for

their historic cemeteries. There are a number of old cemeteries near Ash Fork such

as Cedar Glade, Puntenney, and Gleed. Many railroad workers and people from

settlements were buried in these. Drake train station (which changed its name

from Cedar Glade in 1920), was built in 1901.

The last passenger service here was in 1955 and 1969. This depot was

moved to Prescott in the 1970s to become a gift shop. Other historic depots were torn down when

they were no longer used. A few found new uses such as a crew house at Ash

Fork, and a railroad office in Flagstaff. Several were restored for tourist

use, such as Kingman (built 1907, last service 1971, restored 2007); and

Williams (built 1885, last service 1908, used by city since 1994). (Footnote 3).

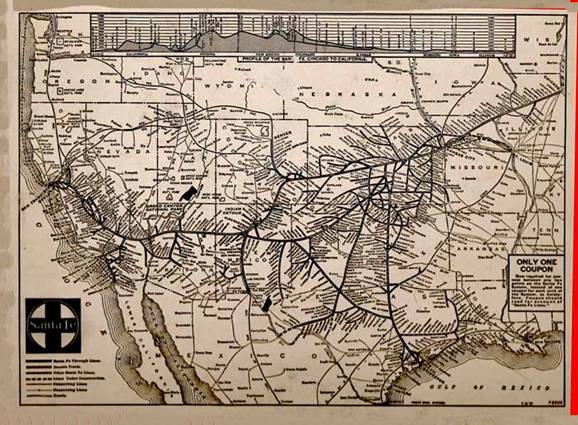

Map from the back

of the 1929 Katchina Doll calendar showing Santa Fe RR routes

The president of the Santa Fe

Railroad, William B. Strong, pushed development and was described in 1893 as:

“The romance involved in the history of the Santa Fe system can scarcely be

more than hinted at here. There can never be again in this country such a life

as was led by President Strong strictly within the bounds of civil life, he was

yet as free as Columbus to discover new commercial worlds....” Later the

author, Charles Gleed, commented that management and commercial considerations

led to the realization that, “the romance in the business has largely gone. It

went with the Indian, who once burned station-houses and murdered settlers

along the line; with the Colorado and Kansas grasshoppers that stopped the very

trains on the track, with the drought that drove the settlers back and

threatened ruin to the whole new field of commerce.” (Footnote

2).

THE

DEVELOPMENT OF THE FAMOUS

ATCHISON

TOPEKA & SANTA FE CALENDARS

The romance and scenes of the

Southwestern country and its Native Americans that the ATSF traveled thru,

though, was preserved and promoted, beginning in 1900, by William Haskell

Simpson. He became the railroad's general advertising agent in 1900. His first

goal was to enhance the company's image and promote tourism to the southwest

where the trains traveled.

Simpson recruited artists, ironically

mostly from famous artists in the Eastern United States, to paint the

Southwestern-themed art to be used in Santa Fe advertising. The first artists

were originally paid with trips to the Grand Canyon. However, as more artists were represented,

the railroad decided to purchase the paintings and avoid future conflicts with

reproduction rights.

The first painting purchased by

Simpson was in 1903 by Bertha Menzler Dressler. It depicted the San Francisco

Peaks in Northern Arizona. Simpson purchased 108 paintings by 1907 for the

Santa Fe Railroad collection. Most illustrated Southwestern landscapes and

portraits of Native Americans as they lived in Arizona.

The art collection was used on all

forms of advertising. In 1907 the annual Santa Fe calendars were first printed,

using these paintings. They were sent to schools and businesses across the

United States. The tradition lasted until 1993. Simpson died in 1933, but Santa

Fe continued to purchase and commission original paints depicting Southwestern

themes until around 1966. Today there are more than 600 paintings, one of the

largest collections of Southwestern art in existence. The collection is now owned by the Burlington

Northern Santa Fe Railroad and displayed nationally in its corporate offices. Some

paintings are also at the New Mexico Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe.

The first calendar (1907) using these

paintings was “Everywhere Southwest” with an Indian design border. In the

1900s, some were design only, but by the 1920s and thru the 1940s, most of the

calendars depicted Native Americans engaged in various activities such as

basket weaving, grinding corn, dancing, hunting. There were no calendars in

1919 and 1920 (government operation).

In the 1940s, scenery became more

prominent, with depictions of landmarks such as “Gallup in the 1880s,”

“Monument Valley,” “San Francisco Peaks”. Some calendar scenes resembled

paintings by the noted Western artist Charles Russell. In the 1950s, Native

Americans were again featured on calendars such as “Navajo Woman,” “Navaho

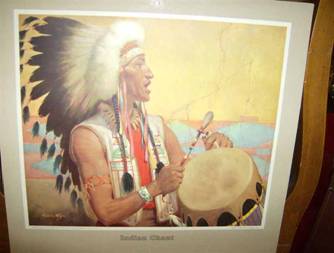

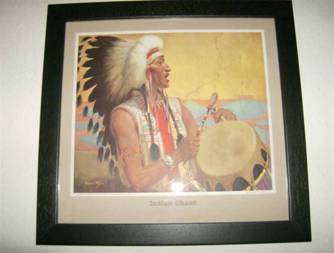

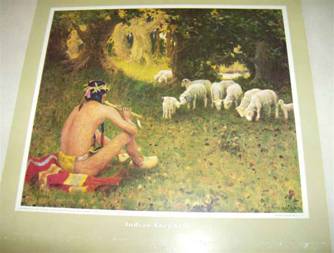

Sandpainter”. etc. One, “Indian Chant”, 1953, is shown below.

|

|

|

L. “Indian Chant”

calendar unframed – R. “Indian Chant” calendar framed

APCRP has collector copies of this

calendar available, unframed, on light cardboard, as a donation to APCRP.

$15.00 + $5.00 S&H Each.

NOTE: Quantities are limited on some collector calendar prints; make

sure to order quickly to assure a copy of the print you want.

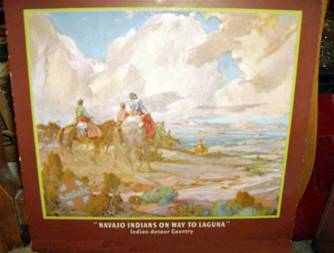

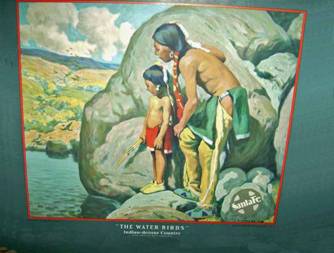

Other calendars available thru Neal Du

Shane as a donation to APCRP are the dreamy, “On the Way to Laguna Pueblo,”

(1934), “Water Birds,” (1937), and “Indian Shepherd.” (1961). $15.00 + $5.00

S&H Each.

|

|

|

L. “On the Way to Laguna

Pueblo” Unframed. R. “Water

Birds” Unframed

“Indian Shepherd”.

Unframed

In the 1960s, the Santa Fe Railroad

had over 600 paintings and decided to reuse four of their paintings for 1963,

1964, 1965, and 1967 calendars. One, “Kachina Doll” was used in 1964. It was

originally titled, ”The Katchina Doll” (1929).

(The word Kachina is spelled several ways.) One copy of this calendar is

available. Unframed.

“The Katchina Doll”

Collectors can tell the difference

between earlier and later versions by looking for the Santa Fe circle and cross

logo. Until 1949, all calendars had the

logo overlaid or watermarked on the image.

The date of publication appears usually below the bottom line of the

framed art, on the right hand side.

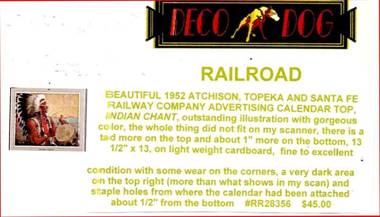

Example of ad for a

calendar for sale today from an Internet dealer

These calendars are a lasting reminder

of the Southwestern country and peoples at the beginning of the settlement of

Arizona, partly brought about by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad.

FOOTNOTES

1.

“Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe, The

Route 66 Railroad!” aroundaz.com. 2003-2007. Internet.

2.

Charles S. Gleed, “The Atchison Topeka

& Santa Fe,” The Cosmopolitan, Feb. 1893. Reprinted in Catskill

Archive. Internet. This page originally appeared on Thomas Ehrenreich's

Railroad Extra Website.

3.

“Passenger Train Stations in Arizona,”

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia.” Internet.

4.

“Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Company

Calendars,” Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Company Calendars Website.

These prints are donated to support

APCRP,

through the generosity of Ed and Kathy Block

Call in advance of placing an order to verify availability

Make Donation Checks Payable and mail

to:

Neal Du Shane / APCRP

1224 Canvasback Court

Fort Collins, CO 80525-8835

1-970-227-3512

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet Publication

Version 050510KB

WebMaster: Neal Du Shane n.j.dushane@apcrp.org

Copyright

© 2010 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this

website may be used

for personal family history purposes, but not for financial profit or gain.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer & Cemetery

Research Project (APCRP).