Presentation

Version 123012

Hard Copy

$30.00 APCRP

Version

083007

Presentation

Version 123012

Hard Copy

$30.00 APCRP

Version

083007

Table of

Contents

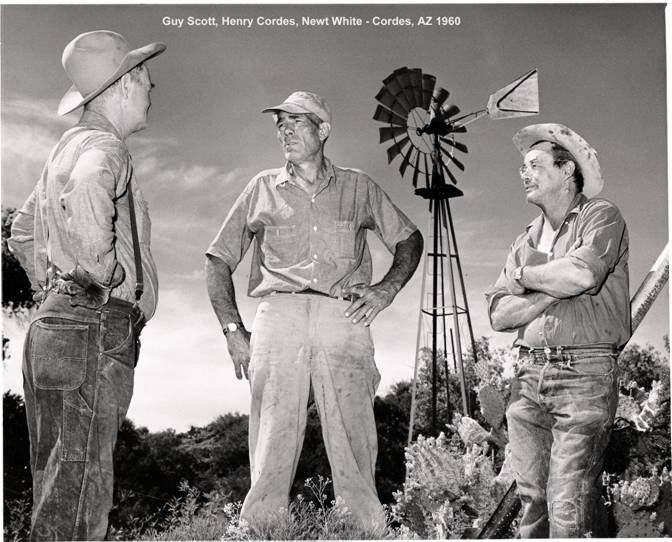

Guy Scott, Henry Cordes, Newt White

Cordes Store began in 1883; Hank 3rd Cordes

Cordes Store a treasure trove of Cordes family history

Guy Scott, Henry Cordes, Newt White

From:

Arizona Ghost Towns and Mining Camps, By: Philip Varney

Cordes is 8 miles

southeast of Mayer. John Henry Cordes came to

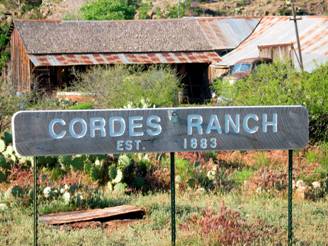

In 1883, Cordes, his wife "Lizzie," and year-old son Charles moved north to Antelope Station, where for $769.43 he purchased a small adobe stage stop along the route of the California and Arizona Stage Company. When Cordes applied for a post office as Antelope Station, he was turned down because of possible confusion with another Antelope Station. As an alternate, Cordes chose his family name and served as the first postmaster.

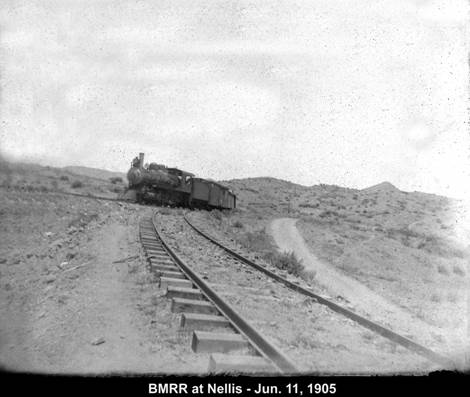

The Cordes stage stop soon took on other functions. When mines opened in the area, the outpost became a supply depot and bank for the miners. It later became a stop for sheep drives en route to winter or summer ranges. John Cordes built pens, a shearing corral, and sheep-dipping troughs. Eventually Murphy's Impossible Railroad built a siding called Cordes Station, 3 miles to the west at Cedar Canyon.

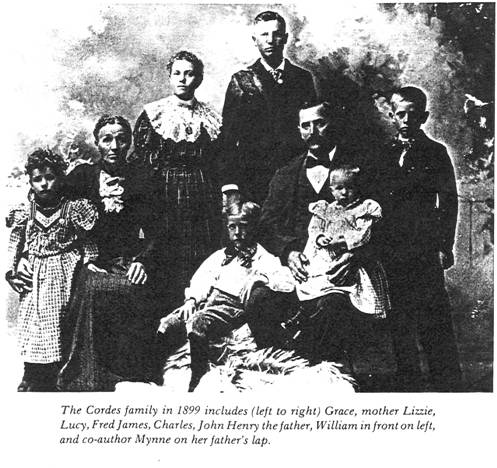

Over the years at Cordes, Lizzie bore six more children. This hard-working family did have moments of enjoyment. After the Bradshaw Mountain Railroad established Cordes Station, the Cordes family would celebrate the Fourth of July by picking up a 100-pound block of ice in a gunnysack dropped at the railroad siding. By the time they returned home the ice weighed only 75 pounds. Family members took turns working the hand cranked freezer, relishing their once-a-year ice cream treat.

Cordes' eldest son,

Charles, took over his father's business

in 1908 after attending

The Cordes post office closed in 1944, but the town lived on until the 1950s, when it was bypassed by the Black Canyon Freeway. A new stopping place, Cordes Junction, was established. The Cordes family got in on the ground floor there, too. In anticipation of the new route, three Cordes brothers filed homestead claims. A gas station and restaurant at the junction today were built by Henry Cordes.

Still standing at the original town site is a gas station that closed in 1973, the family home, and a barn constructed in 1912. The Cordes family continues to live at the site, a testament to the pioneer tradition of putting down roots, doing hard, enterprising work, and adapting to the changing times.

Cordes Station - 2006

Originally known as Antelope Station, taken from the stream that runs nearby, the first keeper for this station appears to have been William Powell, as we learn from an article in the Miner dated April 12, 1878. Later on, this location was renamed Cordes after the family that owned it beginning in 1882.

Letter From Antelope

We are camped for the night at the hospitable station of Wm. Powell,

which by the way, is a credit to this section of what was once the stronghold

of the Apaches. One mile west from this place the noble, brave Townsend was

murdered by these fiends. Were all the Indian lives in the Territory sacrificed

as a retribution for that of Townsend, the scout and frontiersman, it would

fall short of accomplishing that end. From Spaulding station on

the

The Miner of June 25, 1878 reported that Alfred LeValley, of the Prescott and Gillett Stage Company (factually, Caldwell and LeValley Stage Company) had rented the station at Antelope and had moved his family to that location. LeValley told everyone that his reason for doing so was to lower his cost of boarding horses for the stage line. Later, circumstances convinced many that he was really setting the stage for a quick escape from creditors.

By February of 1879, Jack McAlister was the new keeper at Antelope Station. In November of that year, McAlister sold out to Otto Bolin and possibly his brother for $1,500.

The story of Otto Bolin and his murder at Antelope station is typical

of many unnecessary deaths on the

The scene was Otto Bolin's house at Antelope Station. Present inside the house, were John Grasse, a traveler who had stopped I for a while due to muddy roads in the area, Otto Bolin, station proprietor, and Wesley Clanton. a stockman from Big Bug. Outside, just a few yards away, was hired hand, Adam Mannsmann, chopping wood. It was a cold winter day, January 21, 1882.

Bolin was serving whisky to Grasse, who, by later

accounts, was already very drunk.

Both men went outside where

Bolin and Grasse made numerous threats to each other and

then Bolin pushed him down again, only this time

Soon Bolin was being chased by Grasse who had a knife

in his hand. Bolin suddenly stopped and grabbed

Bolin also passed by Clanton who, by then, was

outside looking for his horse so that he could leave the premises. Bolin told

Clanton, "He has stabbed me right through the heart I am going to

die." After Bolin went inside,

Clanton entered the house and found Bolin stabbed in the left breast. He asked Bolin he wanted a doctor but Bolin said it was no use he could not get there in time. Bolin was then asked by Clanton if he wanted his brother at Tip Top notified. Again, Bolin exclaimed it would be of no use. Bolin asked Clanton to sew up his wound which Clanton obligingly did.

Clanton then left the house and went to Bumblebee to send word to Bolin’s brother and notify the authorities. By evening Clanton returned to Bolin's side and advised him that his brother had been called for whereupon Bolin asked if he was told to come "quickly”. Clanton said he had done that.

Bolin asked Clanton if he thought he might survive the wound. Clanton judiciously told Bolin that he was not too familiar with wounds of that type but thought he might live. Bolin died at 3 a.m. the next day.

Nearly a year later, on January 25, 1883, John Henry Cordes purchased the station from Otto Bolin's brother, Augustus, for $769.43. Cordes had come to Antelope from Gillett where he had labored at the Tip Top mill for a couple of years. There he worked two shifts a day, night shift at the mill, and day shift tending bar at a local saloon, saving money to buy the station.

John Henry brought his wife, Lizzie, to Antelope with him and

together they raised a large family. In 1886, Cordes applied for a post office

using the name Antelope. Because of the confusion with

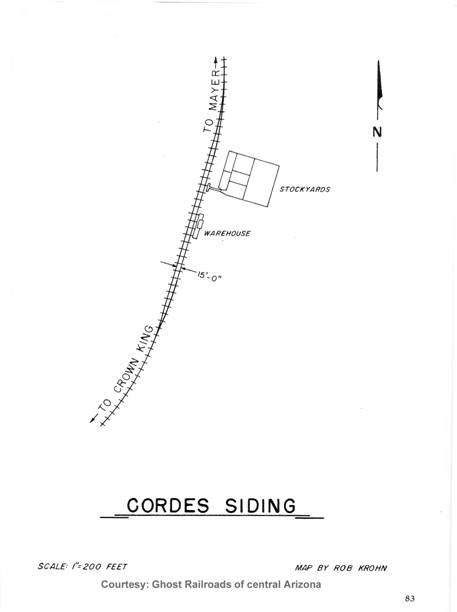

CORDES SIDING

1902-1939

From: Ghost Railroads of Central Arizona

by; John W. Sayre

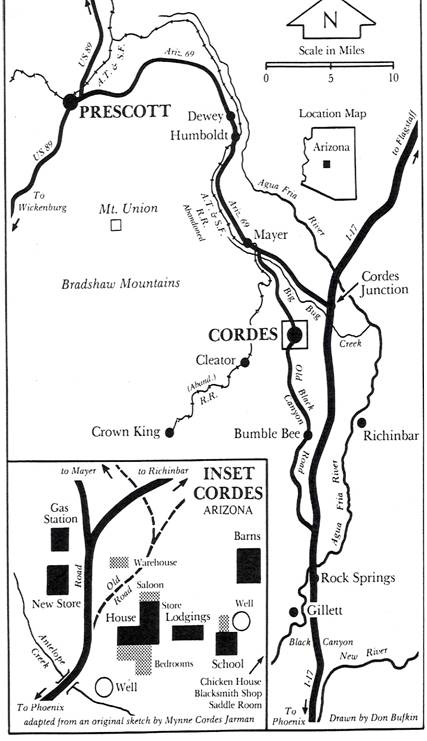

The community of Cordes, a quarter-of-a century

older than the Bradshaw Mountain Railway,

owed its early existence to the Black Canyon Stage Route.

The little settlement was founded in 1875 as a stagecoach stop and change point

for horses on the road between

Mountains in 1875 and worked several years at the.

Tip Top Mine before entering the stage business at

Antelope. Prior to the completion of the

The economy and population of

The

Like Joe Mayer's community, Cordes was on

the sheep trail between

Prior to the arrival of the Bradshaw Mountain Railway in 1902, mining supplies into that range were shipped over the few good wagon roads that existed. Many mines received their supplies and equipment from Prescott via Cordes. With the exception of a few worthless prospect holes, there was no mining activity in the immediate vicinity of Cordes. However, the Richinbar Mine and numerous other mines a few miles away received supply shipments through the small community.

Wagon roads and direct freight routes were eventually built that served the mines and communities to the west of Cordes, but despite the fact that it was bypassed, the settlement managed to survive.

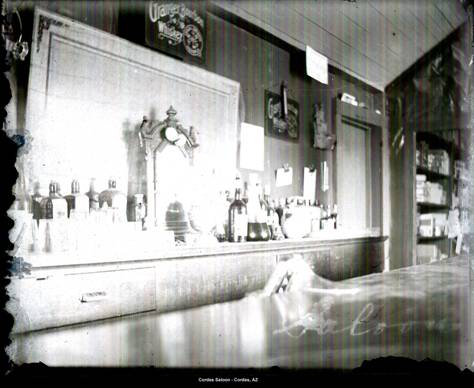

The community even displayed many of the signs of "permanence." Along with the post office, saloon, and store, the community supported a local school district. In 1897, the one-room schoolhouse was filled with fourteen students. The full-time population of Cordes was twenty-five at the turn of the century. Several of the local residents served as election officers for the general elections; they traveled to the general store at Turkey Creek where they cast their ballots and assumed their civic responsibilities. A shallow well provided plenty of water for the residents, and the deputy sheriff in Mayer provided any law enforcement that was necessary. The saloon and general merchandise store did especially well during the sheep drives and during the construction of the B.M. Ry. (Bradshaw Mountain Railway)

The rail of the B.M. Ry.

passed four miles to the west of Cordes. The difficult terrain of

The Greek and Italian stonemasons on the railroad construction crews spent as much time as possible in Cordes. The men enjoyed playfully teasing the children and bought a great deal of wine and liquor. They drank, danced, and sang until early morning to forget the hazards, hardships, and loneliness of their work. These workers constructed hundreds of retaining walls and drainage boxes without the use of mortar. The craftsmanship of these skilled workers was exceptional and made their talents much sought after.

In 1902, a short siding

was laid just north of

The completion of the

railroad to Crown King brought to a virtual end the shipments of

mining supplies from Cordes to the inner canyons of the

The early powerlines into the area were installed at great expense and served only the large mines. Cordes was not near any of those mines or their powerlines. The community did not have power from a public utility until long after most other towns had grown accustomed to the luxury.

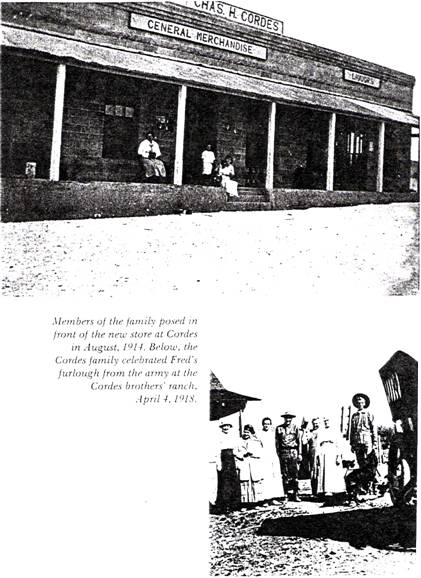

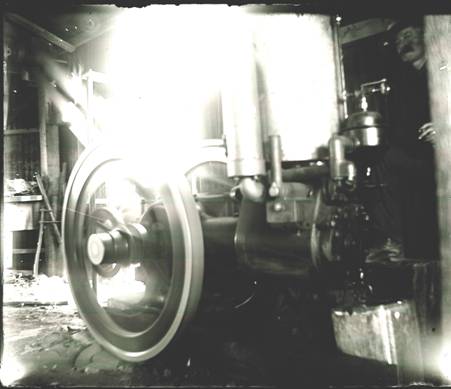

A new chapter was written in the history of the little town in 1910. The elder Cordes retired and turned the businesses over to his son. Charles H. Cordes, heir to the community, constructed a new building for the store and saloon. The new structure, like the one it replaced, did not have electricity. The convenience was added circa 1918 when a generator was obtained and the building was wired for lights; powerlines finally reached the community in 1941. With the completion of the new store, the old building was used exclusively by the family as a residence. A fine grand opening celebration was held on the Fourth of July, 1910; people from the surrounding area and friends from as far away as Prescott were on hand to help christen the "modern" building. The "old fashioned" festivities were enjoyed by everyone present and were the talk of the countryside.

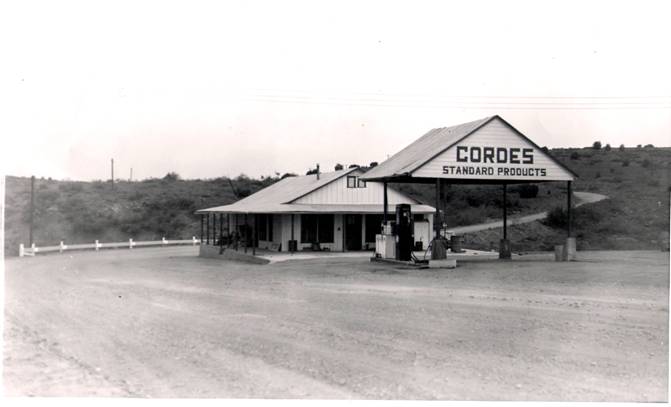

Other construction

projects soon took shape in Cordes; a barn was built in 1912, and a gas station was opened in 1915. The gas station was one of the first in the area and was built

to service the automobiles that were using the

Recreation in the community was similar to that in other Bradshaw Mountain towns of the period. The ever-popular reading, singing, dancing, card playing, hunting, and athletic competitions were enjoyed in Cordes. Though isolated in some respects, it was a "one-horse" town with a unique cosmopolitan flavor. Although the community was somewhat isolated in that it received electricity and phone service long after neighboring communities, it was not nearly as remote as might be thought. Travelers on the Black Canyon Road, first in stagecoaches and later in automobiles, kept the residents of Cordes informed of the latest news. People, attitudes, and styles of all kinds went through Cordes and exposed the townspeople to concepts and ideas from throughout the world.

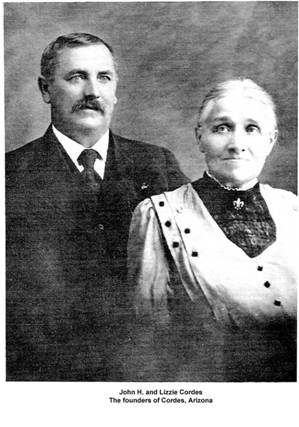

John H. and Lizzie

Cordes, the founders of

The increase in vehicle traffic, though renewing life to Cordes, signaled the beginning of the end for Cordes Siding. The siding received minimal use after 1908, being used almost exclusively for sheep and cattle shipments. As trucks became more durable and dependable in the" late teens, they replaced the railroad as the prime shipper of livestock from the area. The removal of the rail from Cordes Siding back to Blue Bell Siding in December 1939 did not have much of an impact on the community.

The little community of Cordes continued to do well into the forties. The population was about twenty in 1942. The saloon was replaced by a drug counter in the general store, but it was the settlement's gas station that kept the town alive. The post office was discontinued in November 1944. The community was bypassed again when the new Black Canyon Highway was constructed two miles east of town.

The Cordes General Store constructed in 1910 burned to the ground in the 1940’s, but much of the original stage station still exists, incorporated within the walls of the old house. The gas station, which closed in 1971, and the weathered barn still watch over the road they served for sixty years. Henry Cordes, grandson of John Henry Cordes, resides in the family house. At the railroad siding, a small corral, sun-bleached concrete foundations, and the railroad grade are all that are visible.

by

Robert B. Bechtel and

Mynne Cordes Jarman

To THE MODERN INTERSTATE HIGHWAY TRAVELER, Cordes junction is a blur of gas stations and restaurants on 1-17, fifty seven miles north of Phoenix, where Route 69 splits off from the freeway and winds northwest to Prescott. There are three gas stations, two restaurants, a row of rural mail boxes, and the dust and commotion of the interstate exits spilling their cars onto dirt roads. One of the dirt roads leads south to Cordes Lakes Development, a collection of new tract houses; the other leads north to Arcosanti, City of the Future. Although Cordes Junction is neither city nor development, merely a stop along the way, it has a claim to history that goes back to pioneer territorial days. In many ways Cordes junction is the direct descendant of the stage stop that began at Cordes, three miles west of 1-17 on the Crown King Road.

As one turns west on the road to Crown King, the rolling hills and the dips and curves make clear that rural Arizona is taking over from the interstate. After roller coasting a few arroyos, the shiny iron roofs of Cordes come into view, with the small house trailers of the caretaker's compound, the bare wooden barn, and the weather-beaten boards of the house and its few crumbling satellite buildings. A metal skeleton of a roof offers meager shelter to the gas station, and nearby stands the blank cement-block face of the closed store. The place looks deserted in contrast to the activity at the junction, as though it had been built and left behind a long time ago. Yet the modern pick-up trucks and a new trailer home to the north speak of current life, and one is struck by this incongruity of past and present. But the past speaks more clearly here, and one can only wonder how this place could grow so far from the highway and why it now looks abandoned. The story is longer than one might guess from the age of the wood on the barn and house. It goes back over 100 years to the time when the road that goes through Cordes was the only route north from Phoenix to Flagstaff.

Long before the interstate was built, the first passage north through the Bradshaw Mountains was called Black Canyon Road. The Bradshaw Toll Company had been founded to build the road on June 8, 1871, (1) but so hazardous was transportation in those days that a long succession of companies followed and went into bankruptcy when they attempted to provide passenger, freight, and mail service across the Bradshaw’s. The California and Arizona Stage Company, with main offices in San Diego, finally pioneered the route in 1875 with service to Prescott, Wickenburg, Phoenix, Florence, and Ehrenberg.

The first building at what is now Cordes was erected by a man named Powell in 1875 in conjunction with the operation of that stage service. The location was called Antelope Station after the nearby creek. The original building was adobe, and although homesteaders had tried to prove up on the land before Powell, none had succeeded in putting up a building. The first recorded land sale was from M. J. McAlister to the Bolin Brothers (2) on November 24, 1879, for $1,500. (3) On January 25, 1883, John H. Cordes, a stocky, dark-haired, sharp-eyed German, purchased the station from Augustus Bolin for $769.43. (4) From that time on, the history of the area became that of the Cordes family. (5)

John Henry Cordes was born in or near Bremen, Germany, on June 2, 1850. He spoke little about his life in Germany but it seems clear from remarks to his children that he left Germany to avoid military service. He emigrated to New York in 1869 and worked in a sugar refinery. He told tales of transferring 300-pound barrels from one level of the warehouse to another. He worked at several jobs including one in a candy factory.

One story says that he met his wife

while working as a storekeeper. In any

case, it is certain that he met Elise Schrimpf, another hard-working German

immigrant with ash-blonde hair, while they were working in New York. Elise was

born in Minten, Westphalia, Germany,

on March 8, 1853. She remembered digging potatoes with her family as a girl.

They "fed the small ones to the pigs

and stored the big ones." She also remembered going up to the second floor of the house in order to

avoid floods from the river. She emigrated at age eighteen to the U.S. with her

sister Johanna and found employment in New York as a maid

with a wealthy Jewish family. Elise and John Henry met and romance blossomed, but John Henry, following the tradition of

seeking fortune before marriage, journeyed west in 1875.

One story says that he met his wife

while working as a storekeeper. In any

case, it is certain that he met Elise Schrimpf, another hard-working German

immigrant with ash-blonde hair, while they were working in New York. Elise was

born in Minten, Westphalia, Germany,

on March 8, 1853. She remembered digging potatoes with her family as a girl.

They "fed the small ones to the pigs

and stored the big ones." She also remembered going up to the second floor of the house in order to

avoid floods from the river. She emigrated at age eighteen to the U.S. with her

sister Johanna and found employment in New York as a maid

with a wealthy Jewish family. Elise and John Henry met and romance blossomed, but John Henry, following the tradition of

seeking fortune before marriage, journeyed west in 1875.

His ship landed at Panama, where he took a train across the Isthmus and then boarded another ship for San Francisco. Another series of jobs followed until he had enough money to leave for Los Angeles. While in Los Angeles he noticed land for sale at Eighth and Hill Streets for ten dollars an acre. It was not worth it, he felt, because is was nothing but sand dunes.

In Los Angeles he earned enough money to take a ship around Baja California, up the Gulf of California to the Colorado River and Yuma, and then a paddle-wheeler to Ehrenberg. One story says that he helped pole his way to Ehrenberg. From there he took the stage through the Vulture Mine area to Wickenburg. He finally reached Prescott after a year of wandering and stopping to work along the way. At Prescott one of his jobs was mixing mud to make the bricks for the Yavapai County Court House. At Prescott he bought himself a burro and camping equipment and set out over the Bradshaw’s to Crown King. Another tradition has it that he began his burro trip from Goodwin. Finding neither riches nor employment at Crown King, he went on down the mountains to Gillett, where he found a job in the ten-stamp mill that processed ore from the Tip Top mine at the southern end of the Bradshaw’s.

At Gillett John Henry was an amalgamator operator, a job that involved using mercury to draw gold out of the ore concentrates. This process is still used today in some gold dredges.

Considering this his first "permanent" job, John Henry felt the time had come to summon Elise. She came west by train in the company of Mr. and Mrs. Bury, who were traveling to San Francisco. From there she traveled alone by train to Los Angeles and Yuma. She remembered getting off the train at Yuma and seeing her first Indian in a breechclout. Her children were never able to find out exactly what was so terrifying, but it was clear that Elise was "scared to death" and quickly returned to the train. She also remembered hearing two prospectors talking about the delights of "Arizona strawberries" and enjoyed a delicious anticipation until she learned that these were only beans. She arrived at what was then the railhead at Maricopa, where John Henry was waiting, and they took a stage to Phoenix. At some point after arriving in Arizona, Elise adopted the nickname "Lizzie," and this was the name she was called by for the rest of her life, even signing legal documents as Lizzie Cordes.

They were married in a small church near the Arizona Canal on October 30, 1880, and left immediately for Gillett. Their wedding night was spent on Biscuit Flat where what is now the Carefree Road and 1-17 meet. Their only light on that romantic occasion was a wick stuck in bacon grease.

When John Henry and Lizzie arrived, Gillett had quieted down from two previous years of turmoil. The town seemed to have had more than its share of murders and lynchings; in one case the sheriff was shot so a mob could lynch a murderer. Gillett was reputed to have everything but a jail and a church. The Arizona Miner of April 12, 1878, reports the views of Mrs. Eliza Edwards: "Only one thing I regret in Gillett, and that is the little regard in which many people hold God's sacred day. It is nothing but hammer and saw on the Sabbath from morning until night."

One of the Cordes's neighbors in Gillett was the famous pioneer Charles T. Hayden, who operated a store there. Jack Swilling, founder of Phoenix, served as chairman of the local real estate organization. He chaired the meeting which named the town after Dan B. Gillett, superintendent of the Tip Top mine. 6

For three years the Cordes family remained in Gillett, where their first son, Charles Henry, was born on February 11, 1882. John Henry had been saving his money by working night shift at the mill and tending bar by day. By 1883 he was able to buy Antelope Station. The Cordes family moved there on January 31, 1883, six days after the purchase. (7) The first few years were marred by the tragedy of their second son's death. Henry George Cordes, born September 19, 1884, died on December 8, 1887, a little more than three years old. Although the family never knew the cause of death officially, Lizzie later came to believe it was spinal meningitis. Among the younger children, however a tradition grew up that Henry George died from eating poison berries, and they identified a certain shrub as "Henry's poison berry bush."

In 1886 John Henry applied for a post office using the name Antelope but was turned down because it could be confused with Antelope Valley, which later became Stanton. He reapplied, using the family name of Cordes, and the first official day of postal business began on June 9, 1886. That first post office was nothing but a red cupboard built into the eighteen-inch-thick adobe wall in the southwest corner of the house. From that time on, the station became known as Cordes.

The history of Cordes is a story of

adapting to the various economic changes that swept across the country and

state and bankrupted many less-resourceful entrepreneurs. John Henry fed his family by exploiting several

opportunities that the location afforded. Although he was too late for the

placer gold rush of the 1860s, prospectors continued to comb the Bradshaw’s,

and his station became the supply station, post office, and bank for these

itinerants. Many men would work through the summers high in the mountains

cutting timber and in the fall find themselves a camp near water. The practice

was to "sink a barrel" for a well, put up a

tent for shelter, and prospect all winter until logging began in the spring.

Joe's Gulch, one mile east of the main

house at Cordes, was named after Joe Steinmetz, an old prospector who lived

at a dugout spring there. In the early days there was also a sprinkling of

trappers who caught lions, coyotes, bobcats, and foxes.

The history of Cordes is a story of

adapting to the various economic changes that swept across the country and

state and bankrupted many less-resourceful entrepreneurs. John Henry fed his family by exploiting several

opportunities that the location afforded. Although he was too late for the

placer gold rush of the 1860s, prospectors continued to comb the Bradshaw’s,

and his station became the supply station, post office, and bank for these

itinerants. Many men would work through the summers high in the mountains

cutting timber and in the fall find themselves a camp near water. The practice

was to "sink a barrel" for a well, put up a

tent for shelter, and prospect all winter until logging began in the spring.

Joe's Gulch, one mile east of the main

house at Cordes, was named after Joe Steinmetz, an old prospector who lived

at a dugout spring there. In the early days there was also a sprinkling of

trappers who caught lions, coyotes, bobcats, and foxes.

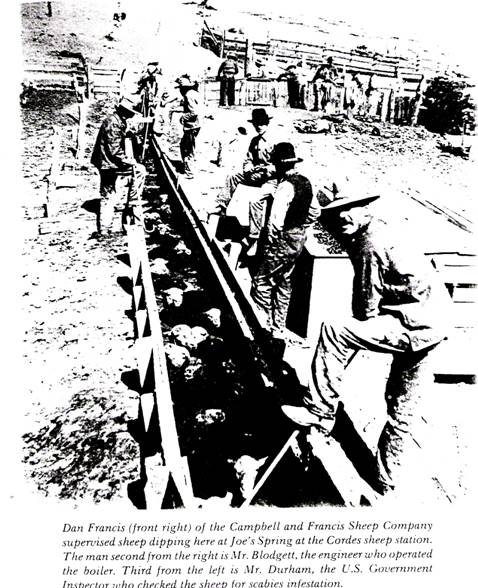

A third family enterprise eventually changed the station into a sheep-supply center. In 1875 William H. Perry had brought sheep into the Williams area. He sold them in 1880 and brought cattle to raise on the Agua Fria River eight miles to the east of Cordes. Perry's partner, George Helm, brought sheep to the Big Bug, also east of Cordes. Meanwhile, in the north, sheep ranching around Flagstaff grew into a major industry. Harland Gray, Hugh Campbell, and Dan Francis ran large herds. The Campbell-Francis partnership had twenty-eight bands of sheep with 2000 in each band. Harry Henderson and Woolfolk had six bands. At first, sheep herders were Mexican, but later shepherds were imported from the Basque area. Locals called them "Boscos."

In response to the demands of the new business the buildings at Cordes underwent gradual change. Before the turn of the century a store and bar were added, making the original building L-shaped. A warehouse was built in front of the house.

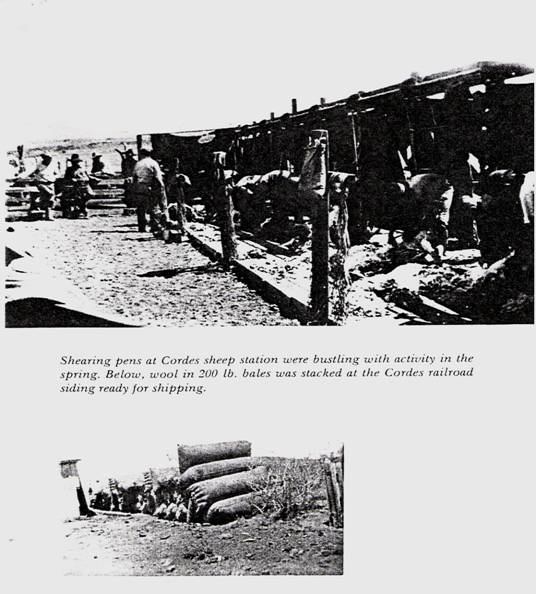

Cordes began to serve as the supply

center and shearing-and-dipping station for sheep drives. Since it was

conveniently located on the drive path between the summer range near Flagstaff and

the winter range south of the Black Canyon from New River to Cave Creek, Peoria, and Beardsley, it was a natural stopping

place. The fall and spring drives became a part of the ebb and flow of life at

Cordes.

Cordes began to serve as the supply

center and shearing-and-dipping station for sheep drives. Since it was

conveniently located on the drive path between the summer range near Flagstaff and

the winter range south of the Black Canyon from New River to Cave Creek, Peoria, and Beardsley, it was a natural stopping

place. The fall and spring drives became a part of the ebb and flow of life at

Cordes.

During the drive periods, as many as seventy-five to 100 men would be looking for a place to eat and sleep. Some would camp in tents, others in the barn, and still others in wagons. Most were fed in shifts at the dining room of the main house.

The "sheep" year would begin with the drive south, lasting from September to November. It was then that the shepherds would stock up on supplies for the winter range. The drive north would begin in February, and shearing and dipping would take place throughout March and April.

A shearing pen was built for shearing wool by hand. With the old hand clippers one man was able to shear twenty to twenty-five sheep per day. In 1905 a man named Wynne brought gasoline-powered shearing machines, and the number sheared increased to sixty per day. As shearers trimmed the fleece, it was kicked aside so they could move to the next sheep. The wool-tiers, standing nearby, gathered each fleece into a bundle and tied it with a jute string. The lied fleeces were then thrown into a bin on wheels which was taken to a nearby circular rack from which the four-foot by eight-foot sacks were hung. The wool "stompers" would then stamp down the fleeces until the bag was full and sew it shut. The bags, weighing over 200 pounds were then stacked until they could be hauled to a railroad siding. A spur was run from the Prescott and Eastern Railway, and for a time Cordes had its own railroad siding just three miles away.

Dipping followed the shearing. All sheep had to be dipped before going on the reserve. When the sheep were examined for scabs, those with several scabs would be dipped twice. Every sheep went at least once through the forty-foot-long troughs, which were deep enough so the sheep would have to swim, and men would be stationed along the sides to prod them with hooks and push their heads under. Sheep dip was a mixture of one sack of lime with two sacks of sulfur.

By May station activity would come to a halt, and the family would spend a rather languid summer. The Fourth of July celebration was a welcome break. Ice, ordered from Prescott, would be delivered in a gunny sack at the railroad siding. At train time the family would rush to the siding with a buckboard, cover the ice with canvas and blankets, and hurry back with it to the store. By the time this trip was over on an Arizona summer day, the one-hundred pound block would weigh only seventy-five. Ice cream was made for the celebration with salt in a hand-cranked freezer.

When sheep-dip troughs were built on Joe's Gulch, a mile-long pipeline was laid to Joe's Spring so that a constant water supply was available. For the house, a tank was built just outside the kitchen door on the southeast and was promptly dubbed the "barrel house" by the children. It was filled by a hand pump on the well on the bank of the creek. Water for house use was dipped out by buckets and carried into the kitchen. Anyone who noted that the barrel was becoming low went to the well and turned the pump wheel until someone in the house rapped on the pipe to signal that the barrel was full. Water failed in a second well, dug about 1905, and its windmill was moved to the older well near the creek, where it is today.

John Henry managed the store, sheep installations, and post office until 1908, when he sold the station to his eldest son Charles and retired to Prescott with his wife and two youngest daughters. The sheep-station business had been so successful that he was able to retire "in comfort." In 1911 he moved to Tempe so that his daughters could attend Tempe Normal School. When World War I began, Lizzie and John Henry moved to Turkey Creek to help their son William on his cattle ranch. On March 19, 1919, John Henry Cordes died at the ranch from influenza, just one of the many victims of that worldwide epidemic. He was remembered as a man who bore no ill will to any person and whose honesty was above reproach. Lizzie moved to Prescott and then to Mayer, where she died on August 19, 1929.

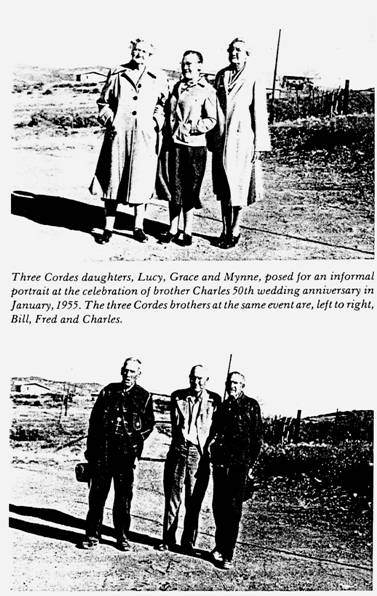

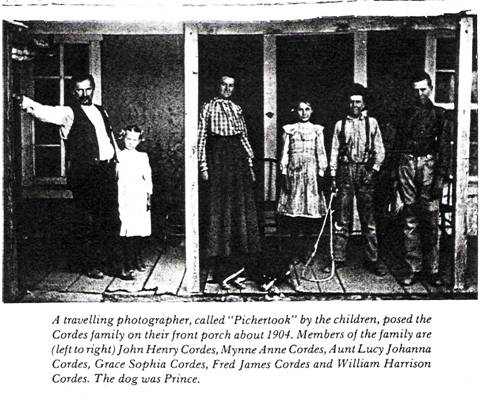

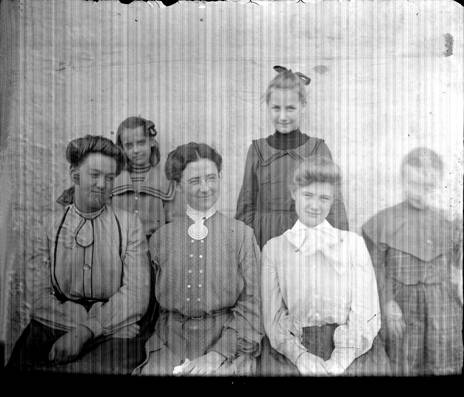

During those early years, while Cordes was developing into a sheep station, five more children were born to Lizzie and John Henry. Lucy Johanna Cordes was born December 18, 1886, and William Harrison Cordes and Frederick James Cordes, the third and fourth sons, were born March 11, 1889, and October 8, 1891, respectively. Grace and Mynne, the last of the second generation, were born on February 23, 1894, and November 22, 1896. All the Cordes children after Charles were born in their home without a doctor; only a midwife was in attendance.

The second generation grew up at Cordes. Charles, Lucy, Bill, Fred, Grace, and Mynne went to their first years of school at Big Bug School, located near the present trailer court at Cordes Lakes Development, four miles east of Cordes. John Henry bought a ranch at that site so that Lizzie and the children could live there and attend school for eight months of the year. At the end of the 1903 term, the Big Bug School was closed for lack of pupils, and the Cordes children had no school until John Henry built the small schoolhouse at Cordes station in 1905.

The first teacher was a Miss Eckerman. She lasted only that first year, after which she departed in pursuit of what was then called a "heart-in-hand" romance. During the early 1900s young men frequently advertised in newspapers for young ladies contemplating matrimony. Such newspapers were often referred to as "heart-in-hand" papers, and the resulting romances were similarly labeled. Miss Eckerman followed her heart to Washington State.

Katherine Barnett taught school for three months and then left to attend Tempe Normal School. She was replaced by Harriett Meritt, who completed the school term. Carrie Ware was the teacher for the third and last year at the little schoolhouse, and she left with a heart-in-hand sweetheart. The following year, Grace and Mynne moved to Prescott with their parents to attend school. They were tentatively placed at the fourth- and fifth-grade levels but before the year was out, Mynne finished the sixth grade, and Grace finished the seventh, a testimony .to their education at the little schoolhouse, heart-in-hand attritions notwithstanding. The schoolhouse was converted then to rental sleeping quarters during the sheep drives.

That little schoolhouse was the social center of Cordes. Dances were held to the music of a hand-cranked phonograph during the lulls between drives. Cowboys, prospectors, schoolteachers and all would crowd into the tiny fifteen-by-fifteen-foot space.

Other dances were held at the old Store at Cleator and in a large building at Parker Flat two miles to the north. The Cordes girls would ride to the dances with divided skins, change for the dance, and change back for the ride home. One Fourth of July the dance at Parker Flat lasted all night. In addition to dances, card games were a favorite pastime. Games like 7-Up, Cinch, and poker consumed many hours.

About

the only German custom that the Cordes family kept was to serve beer and cheese

at 10 every morning. Most of the children

followed the tradition but Lucy refused to drink the beer. The only other

alcoholic beverage was whiskey for stomachaches and toothaches. The one time

the children remember their father drunk was from too many sips to still a

toothache. Root beer was brewed from the package advertised by Hires, but hops

and yeast were added for a little zest. The rest of the diet was pure Arizona.

An enameled pot of the chief fare when vegetables were out of season. The Hill

Ranch on the Agua Fria provided local produce which included

cantaloupes and watermelons.

About

the only German custom that the Cordes family kept was to serve beer and cheese

at 10 every morning. Most of the children

followed the tradition but Lucy refused to drink the beer. The only other

alcoholic beverage was whiskey for stomachaches and toothaches. The one time

the children remember their father drunk was from too many sips to still a

toothache. Root beer was brewed from the package advertised by Hires, but hops

and yeast were added for a little zest. The rest of the diet was pure Arizona.

An enameled pot of the chief fare when vegetables were out of season. The Hill

Ranch on the Agua Fria provided local produce which included

cantaloupes and watermelons.

Birthdays were celebrated with Lizzie's famous walnut cakes. The wild walnuts were too small, so the nut cakes were always from the larger "store bought" walnuts.

Christmas was largely ordered out of the Sears and Montgomery Ward catalogues. Boxes would arrive at the railroad siding to be hidden away from the children until Christmas Day. While the children still believed in Santa Claus, a cedar tree was their Christmas tree. Later, when they lost the belief, there was a period without trees. As the children got older, they reinstituted the tree on their own. The traditional turkey and trimmings were the dinner fare.

Charles Henry Cordes attended Yavapai County schools until the eighth grade and then got a certificate in bookkeeping and accounting from Los Angeles Business College. Prior to buying the station from his father, he kept the books for the store. From 1906 to 1908 he went into the sheep business briefly for himself, but that did not succeed and he returned to the station as manager. He married Mary Elizabeth Chastain on May 5, 1908. She had been born in Gainesville Hall, Georgia, on September 3, 1888. Her first job in the West was at the Bashford Burmister store in Prescott. She was a telephone operator in Mayer when they married. The little school house that John Henry had built for his four younger children was their honeymoon cottage until August, when John Henry, Lizzie, Grace, and Mynne left for Prescott and Charles took over the station.

Meantime, the station was

undergoing change. In September of 1908, Charles Henry bought the store and took over as postmaster

on March I, 1909. In that year a new roof was needed on the main house but when

the old roof was jacked up for repair, it was discovered that the adobe walls

were so deteriorated that they needed a new house before the roof could be lowered

again. Consequently, the entire house was rebuilt in wood frame as it now

stands. The store and bar addition, which had been added to the north of the

house before the turn of the century, was converted into a new dining room for

sheep-drive customers. U. S. Department of Agriculture inspectors were present to examine the sheep. And for a

long time Cordes was a training school for government sheep inspectors. There

would be as many as seven or eight during the drives. A three-room motel-like

addition was built to house the inspectors but the overflow would bed down in

the old schoolhouse. Calvin Cordes, Charles's son, remembers that one of

his chores was to keep the water pitchers filled in the inspectors' rooms.

Later, Charles moved the schoolhouse next to the rooming

house to use as a bathroom. The warehouse, built in front of the house, was

moved when a new larger store was built to the west.

Meantime, the station was

undergoing change. In September of 1908, Charles Henry bought the store and took over as postmaster

on March I, 1909. In that year a new roof was needed on the main house but when

the old roof was jacked up for repair, it was discovered that the adobe walls

were so deteriorated that they needed a new house before the roof could be lowered

again. Consequently, the entire house was rebuilt in wood frame as it now

stands. The store and bar addition, which had been added to the north of the

house before the turn of the century, was converted into a new dining room for

sheep-drive customers. U. S. Department of Agriculture inspectors were present to examine the sheep. And for a

long time Cordes was a training school for government sheep inspectors. There

would be as many as seven or eight during the drives. A three-room motel-like

addition was built to house the inspectors but the overflow would bed down in

the old schoolhouse. Calvin Cordes, Charles's son, remembers that one of

his chores was to keep the water pitchers filled in the inspectors' rooms.

Later, Charles moved the schoolhouse next to the rooming

house to use as a bathroom. The warehouse, built in front of the house, was

moved when a new larger store was built to the west.

The six children of the second generation grew up and went their separate ways, yet they managed to return to their place of origin in later years. Lucy and Mynne followed the family tradition and attended the Los Angeles Business College as Charles had. Lucy went to Humboldt. Miami and Cleator and finally settled in Mayer.

William and Fred worked at the sheep station with Charles until they joint-ventured a cattle ranch on Turkey Creek. When Fred was drafted into the army in 1917, John Henry and Lizzie moved to the ranch to help Bill out. When his father died, Fred returned to the ranch and bought it from Bill, who then used the money to start a pack-train business out of Cleator to supply local mines. Fred bought a new ranch at Bumblebee and sold it in 1945 when he retired to Glendale.

Grace and Mynne had both graduated from Tempe Normal School. Grace taught school at various locations in Arizona and later helped found a new community in California called Neubieber.

Mynne began a thirty-year career in government service after teaching at Stoddard, and then retired to Glendale. In January of 1958, the family gathered to celebrate the 50th wedding anniversary of Charles and Mary.

In 1938, Charles and Mary retired from the station, sold it to Henry, their eldest son, and bought

a place in Wickenburg, where they lived while

Warren and Calvin, their youngest sons,

finished high school. They moved to Kingman and finally to Mayer, where Charles died on November 9, 1963, Mary in 1964. Charles was remembered as being a success at whatever

he undertook, but several of his "friends" had relieved him of the

better part of his fortune in bad investments and unpaid loans. Mary was his thrifty counterpart in these ventures.

In 1938, Charles and Mary retired from the station, sold it to Henry, their eldest son, and bought

a place in Wickenburg, where they lived while

Warren and Calvin, their youngest sons,

finished high school. They moved to Kingman and finally to Mayer, where Charles died on November 9, 1963, Mary in 1964. Charles was remembered as being a success at whatever

he undertook, but several of his "friends" had relieved him of the

better part of his fortune in bad investments and unpaid loans. Mary was his thrifty counterpart in these ventures.

Henry E. Cordes, as the eldest son of the eldest son, carried on the tradition of John Henry and Charles in the third generation. The sheep business peaked just after the time of the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934. By this time Henry was already helping his father in the business, and when he took over in 1938, he was made guardian of the area by the Arizona Wool Grower's Association.

The post office was on the verge of lapsing in January, 1912, but the order was rescinded. Service was ordered closed in October, 1932, but again was restored. Henry took over from January 31, 1940, until its final closing on November 18, 1944. The reasons for such threatened irregularity in service are suggested by Henry, and they speak of a common experience among rural postmasters:

The post office and store would serve mostly to the east. You had to go only nine miles northwest to a post office in Mayer, but sixty miles to Payson or forty miles to Camp Verde in other directions. We served people in that eastern section. We never had more than forty boxes, though. Most was temporary and general delivery. I never had more than five rented boxes on a regular basis.

In 1940 the old wooden warehouse behind the store caught fire and spread to the store and post office. Miners from the nearby Golden Belt Mine and from as far away as Turkey Creek and Mayer saw the smoke and rallied to help evacuate the store, saving all the merchandise. Henry rebuilt the store with a cement block face and wooden sides, and it is the building which stands there today.

After the fire I rebuilt the store in 1941. This time I fell heir to some pigeon holes from the mine at Richinbar. I didn't have any lock boxes. The post office and I fell out over financial matters. The inspector wouldn't let me take care of my customers. I knew when my customers would want money orders every month or so, so I would get them with my own money and hold them until they came by. They caught me on that.

Also, I would hold the mail longer than a month. Some would come by once a month and pick up the mail but some would wait longer, and I would hold it for them. Well, the inspector would come by and tell me that under no circumstances was I to hold it for more than thirty days. I don't care what the man says (he says) "send it back." Well, I didn't. Sometimes people were late getting back so I would not send the mail back. The post office was an interfering chore. Sometimes I had to wait there for the mailman for more than an hour. But it was an attraction for business. Times change though. I was glad to see 'er go.

But the Cordes store lasted much longer. Henry recalls:

When I took over the store in 1938, I had to give my Dad an exact accounting. We had $3000 in merchandise. When I opened after the fire we had a grand opening with a band from Phoenix. Our store was a grand merchandising enterprise. It was a damn busy place back in those years. We would ship hay there. Later years we would get three or four tons on a truck from the valley. In the store we had everything from horseshoes to a nickel slice of cheese. We had men's clothes, groceries, a dollar watch to pocket knives. We didn't ever have women's clothes, and I don't remember a single necktie.

We were always there from six to ten every day, seven days a week. We didn't have any hours. One night a man came by at midnight. I got up, went over to the store and sold him five cents worth of gasoline so he could put it in a lantern and hang it in his car. You had to cater to your customers.

In 1948 rumors had spread that the Black Canyon Highway would be reconstructed to bypass Cordes. At this time the road was still unpaved. Not to be outdone if the highway left them, Henry, Calvin, and Charles filed homestead claims on five acre tracts near the proposed intersection of the new highway with the road to Prescott. When the new highway was built, Cordes served as a construction camp and had a trailer park for workers. Henry built a bar and restaurant at the new intersection, three miles from Cordes in 1956. But in 1960, the highway condemned the property to build the new interstate exchange. Henry lost six of the ten acres he owned there. He remembers getting the summons while camping at Lakeside in the White Mountains. Undaunted, he built the Chevron station and restaurant that stand at the junction today. They opened July 4, 1961, but were sold a few years ago.

How did the name Cordes Junction come about? Henry claims that the state highway department had a maintenance camp established eighteen months before the first restaurant. The camp was named Cordes Junction, and the name naturally transferred to the exchange. Says Henry, "I wasn't too happy with it, though."

The family goes on. Henry, in retirement, lives with his second wife Sylvia in the old homestead. He is the third generation occupying the site since 1883. Henry says proudly:

My father had four sons and two daughters. Ray was my professor brother. He taught school since 1934 in Miami, Arizona. Ruby lives in Parker, and she taught school. Edna lives in Page. She taught school. Warren lives in Springerville. Calvin is the little brother and lives in Prescott. He teaches physical education and is a coach. Four of these five were teachers. We all live in Arizona. And Cordes goes on. The family has not only continued: it has prospered through the collapse of stage routes, mining, and the sheep drives, the gain and loss of the railroads and highways. Patsy, Henry's daughter, and her husband built a house north of the homestead for their retirement, beginning the fourth generation of occupancy. Through it all, they have adapted and won a living in spite of the challenges.

Strange portents of the future are growing nearby. Arcosanti, the utopian dream of architect Paolo Soleri, can be seen taking shape to the northeast of the gas stations and restaurants of Cordes Junction. Its promotional activities bring increasing numbers to attend cultural events and workshops. Soleri sees his enterprise as the community of the future.

In the unfolding of the history of Cordes, there were no murders, no discovery of sudden riches, nor any of the overblown expectations that have come to be associated with the settling of the West. Too often Arizona and the other frontier states were looked upon as temporary places to exploit before moving on. We tend to remember the dramatic stories of violence because these are told and expanded upon in books and movies. We seldom think about the people who actually settled the frontier and made it grow. Their lives formed a rhythm that responded to the changes of the land and the nation. And the quiet little places like Cordes are a curious reminder of that long and silent struggle.

1 Corporations Record Book No. I, Yavapai County, p.27.

2 Richard Bolin, one of the brothers, is buried in Cordes cemetery.

3 Record of Deeds, Book No. I, Yavapai County, p. 434.

4 Record of Deeds, Book 17, Yavapai County, p. 87. Presumably there was

a reduction in acreage from the first sale or or prices were 50% lower. The price was not $100 as given

in Cordes manuscripts at Sharlot Hall museum.

5 Ironically, the final deed to the property was not

cleared until much later. Henry Cordes, the grandson, remembers seeing the signature of William Taft on the

original deed, "No papers came until after my Dad's time."

6 1n 1886, a mill was built directly at the Tip Top Mine and Gillett fell into

decline.

7 Not much was

remembered from the stage station operations. The California and Arizona Stage

Company was taken over

by Gilmer. Salisbury and Company July I, 1878. They advertised carrying the U.

S. mails and Wells Fargo Express between Prescott and Maricopa via

Robert

B. Bechtel is a Professor of Psychology at The University of Arizona and

Director of the Environmental Psychology Program. His interest in small towns

goes back to graduate school when he studied small towns in Kansas. His Ph.D.

was earned at the University of Kansas in 1967 and his B.A. came from

Susquehanna University in 1962. His research work included remote communities

in Alaska. Canada. Australia and Saudi Arabia. He was a Fullbright Fellow to

Peru during the summer of 1986. Interest in Cordes was sparked by research on

post offices with the

(Author and source; Unknown)

Transcribed and edited by: Neal Du Shane 1/22/06

When the Cordes Store was first established, it took five days for the four- or six-horse fright wagon to make the trip to Phoenix and back. Now. the third generation operator. Henry Cordes, can go to Phoenix, pick up his loot and be back in the early afternoon of the same day. Such is "progress."

One of the few three-generation stores in the state, Cordes was named after its first founder, J. H. Cordes, who set up shop in 1883, just across the road from the present store. In 1908, son Charles H. Cordes picked up the option, and in relatively recent times, Henry Cordes, since 1937, has been at the helm. The store burned in 1940 and was rebuilt on the same site.

Cordes store has a few other things to distinguish it from the typical country general store. First, there's no sign saying it is a store, or whose store it is, except a mail box on the front step which says simply: "Cordes." Secondly. Henry, a droll fellow, with a great sense of history; and perspective. doesn't worry too much that he is not on the beaten path. Aside from the store, he runs horses and cattle, tinkers with refrigeration and is of the abiding philosophy that nothing should be moved or dusted unless it is about to bite you. Hence the typical small-store clutter, with the usual cold cuts, boxes of shoes, and pliers left on the counter. A sewing machine which is more adapted to saddle repair than the seat of one's pants is in evidence.

Henry has something else going for him, a good, working windmill and sweet water. During the dry times of the 30's. it was the main watering hole in the area.

Originally a watering stop between Phoenix and Prescott when the old Black Canyon road went that way, Cordes finds itself now about three miles from the main drag, and has its trade limited to a handful of natives who wouldn't go anywhere else, and a few off-the-main-stem tourists who are looking for how it was, not how it is. A good gravel road connects Cordes to Mayer and Humboldt on the north, and to Cleator and Crown King on the south. Its 3,773 (feet) elevation and dryness encourage clean, dry, air and typical cactus and catclaw growth.

Sheep and cattle still vie for the open range in this area. and Henry disputes the contention of many that the two varmints and their owners will never mix. "I've heard of a little rumble or two, but on the whole the sheep and cattlemen get along fine. In fact. some of the cattlemen and sheepmen are good friends." He says about 30.000 sheep graze through there even now.

Henry reports that the post office was established there in 1886. and ran uninteirupted until 1946, when. "by mutual agreement." it was removed by postal authorities. Agreeing with Dick Wheaton, of Crown King, Cordes insists it is nearly impossible to run a post office by Washington regulations when the natives of the area are accustomed to neighborliness, not rules and regulations. Since a fourth-class post office operator is compensated according to the amount of cancelled material that goes through his office, postal authorities were continually upset when Henry cancelled many more pieces than he sold stamps for.

"That was because if folks were going somewhere and went by a post office or something, they would buy their stamps there and wait till they got home to mail them." This was partially solved when Henry would urge his customers to "buy local" so he wouldn't be suspected of chicanery. .

"Henry, hold my mail till I get back," was a typical request of customers when they would take off for parts known. Henry would hold their mail. The inspector would arrive. spot a lot of old mail. insist that it had to be returned to its sender, as per regulations. "What was I gonna do, defy the United States government, or send mail back to people who would wonder what was wrong with my mind," Cordes exclaimed.

County: Yavapai Elevation: 3,773 Source: Henry Cordes

Henry Cordes, a Third-generation general store operation in Arizona, runs a low-key operation off the main highway in an area replete with history and nostalgia. He recently received a 50 year plaque from Standard Oil.

In the fall of 2005 while on a history research sojourn to Crown King, I happened upon the Cordes Station/Store in Cordes, Arizona on a Saturday morning, now operated as a business selling unique antiques and memorabilia of the area. As I entered this extremely historic building I had the pleasure of meeting Cathy Cordes a granddaughter of the founder of Cordes, Henry Cordes. Cathy now operates the business on weekends. Between customers, we discussed the history of the area and the Cordes family, to which she has a vast collection of historical text, data and pictures.

On Friday 1/21/06 Gene Simonds from Greeley, CO and myself joined Cathy at the Cordes store and ventured out to see if we could locate the resting place of the people on her document. Cathy took us to the location she believed the internments could possibly be. Sure enough we located the internment of Henry George Cordes a 3 year old who perished in 1887 and located the headstone. Walking slightly farther we discovered the internments of three females and possible three males. We have names for 5 of the seven internments which means there are possible two males buried that we haven’t found their information.

It seems Henry George Cordes a small baby at the time, is interred in this cemetery, and from the gleam in Cathy’s eyes finding this particular plot was important to her. It seems at one time the head stone for this burial, some how over the years it was misplaced and ended up in Black Canyon City as a patio stone. Only in the past year has it been returned to the Cordes family and they would like to locate the burial and place it in it’s rightful place. From the cuts in the bottom of the headstone, it sat in a base which we will research to see if it can be located.

Next time you’re in the Cordes area, make it a point to venture off the beaten path (I-17, Exit 259 follow the Crown King Road to Antelope Creek Road, Approx 2.5 mi) and take a trip into history. The pace is slow; the hospitality is greater, the quality of life is higher than you may be accustomed to. Cathy has a wealth of information regarding the history of this community and the Cordes Family and is a gracious hostess. Cathy operates the store on weekends and you can even purchase an Ice Cold Sodi-pop from the old Coca-Cola cooler, browse the unique inventory that’s for sale, kick back on the front porch and enjoy a few brief minutes away from the hustle of modern life (leave the cell phone in the car). Cordes is well worth your visit, not to be confused with Cordes Junction.on I-17.

Out of respect to the Cordes Family we have chosen not to reveal the exact location of the Cordes Pioneer Cemetery other than to identify it as being in the general Cordes area.

CORDES Cemetery

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cordes, Yavapai County, Arizona |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I -17, Exit 259, Northwest on Crown King Road to

Antelope Creek Road |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Latitude N34 18' 13.3, Longitude W112 10' 0.0 -

(Elevation 3,773) |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Burials = |

11 |

|

|

|

8/30/2007 |

|

Marker |

SURNAME |

FIRST NAME |

MIDDLE NAME |

BIRTH DATE |

DEATH DATE |

COMMENTS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N |

BOLINE |

Gus |

|

|

|

John

Gross Killed Gus - After a drinking party |

|

N |

BOLINE |

Henry |

|

|

|

Brother |

|

N |

BOLINE |

Richard |

|

|

|

Brother |

|

N |

BOMIND |

? |

|

|

|

Female |

|

N |

CAISING |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

CORDES |

George |

|

Sep. 19,

1884 |

Oct. 8,

1887 |

3 yr old |

|

N |

ESPINOZA |

? |

|

|

|

Female |

|

N |

|

John |

|

|

|

Killed

Gus Boline |

|

N |

SHEETS |

Bill |

|

|

|

|

|

N |

SHOEMAKER |

? |

|

|

|

|

|

N |

THUSING |

Nancy |

Hall |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NOTE: |

Out of

respect, privacy and vandalism issues the exact location of the internments

will not be revealed. |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contributors: Cathy Cordes, Neal Du Shane, Gene Simonds |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Material may be

freely used by non-commercial entities, as long as this |

||||||

|

message remains on

all copied material, AND permission is obtained from |

||||||

|

the contributor of

the file. |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

These electronic

pages may NOT be reproduced in any format for profit |

||||||

|

or presentation by

other organizations. Persons or organizations |

||||||

|

desiring to use this

material for non-commercial purposes, MUST obtain |

||||||

|

the written

consent of the contributor, OR the legal representative of |

||||||

|

the submitter, and

contact the archivist with proof of this consent. |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This file was contributed for use of |

||||||

|

Contributor/Archives by: Neal Du Shane - All rights reserved |

||||||

|

Monday, August 27, 2007

On Jan. 21,

1882, Otto Bolin was serving liquor at the Antelope Creek stage stop, located 15 miles south of Mayer,

when he decided to quit serving customer John Grasse. |

7-Up, 19

Agua Fria, 6,

16, 20

Agua Fria River,

16

Antelope

Creek, 27, 28, 29

Antelope Hill,

10

Antelope or

Antelope Station, 8

Antelope

Station, 3, 6, 13, 15

Antelope Valley,

15

Arcosanti, 13,

24

Arizona Canal,

15

Arizona strawberries,

15

Arizona Wool

Grower's Association, 22

Barnett,

Katherine, 19

Barrel house, 18

Bashford

Burmister store, 20

Basque, 16

Beardsley, 17

Beer and cheese

at 10 every morning, 20

Big Bug, 16, 19

Biscuit Flat, 15

Black Canyon, 4,

8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 17

Black Canyon

Freeway, 4

Black Canyon

Highway, 11, 23, 29

Black Canyon

Road, 10, 13

Black Canyon

Route, 9

Black Canyon

Stage Route, 8

Black Canyon

State Route, 10

Bloody

Basin Road, 29

Blue Bell

Siding, 11

Bolin Brothers,

13

Bolin, Augustus,

7, 13, 29

Bolin, Otto, 6,

7, 29

Boscos, 16

Bradshaw

Mountain, 4, 8, 9, 10

Bradshaw

Mountain Railroad, 4

Bradshaw

Mountain Railway, 8, 9

Bradshaw

Mountains, 10, 13

Bradshaw Toll

Company, 13

Bumblebee, 21

Bury, Mr. and

Mrs., 15

by mutual

agreement, 25

Caldwell and LeValley

Stage Company, 6

California and

Arizona Stage Company, 3, 13, 24

Camp Verde, 22

Campbell, Hugh,

16

Campbell-Francis

partnership, 16

Carefree Road,

15

Cave Creek, 17

Cedar Canyon, 4

Chastain, Mary

Elizabeth, 20

Chevron station

and restaurant, 23

Cinch, 19

Clanton, Wesley,

6

Cleator, 19, 21,

25

Cloin, Cathy, 27

Colbert,

Bruce, 29

Copper

Star Restaurant and Bar, 29

Cordes

Calvin, 21, 22, 23, 24

Charles, 15, 23, 25

Charles H., 25

Edna, 24

Henry, 3, 4, 12, 14, 15, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24

Henry E., 22

Henry George, 27

J.H., 25

Johanna, 19

John H., 13

John Henry, 7

Lizzie, 7

Mary, 20, 21, 22

Patsy, 24

Ray, 24

Ruby, 24

Warren, 22, 24

CORDES AND

CORDES JUNCTION, 13

CORDES Cemetery,

28

Cordes Junction,

4, 13, 23, 24

Cordes Lakes

Development, 13, 19

Cordes Post

Office, 4

Cordes School

District, 10

CORDES SIDING, 8

Cordes Stage

Stop, 4

Cordes Station,

4

Cordes Station -

2006, 5

Cordes

Store, 2, 25, 29

Cordes,

Becky, 29

Cordes, Bill,

19, 21

Cordes, Calvin,

21

Cordes,

Cathy, 29

Cordes, Charles,

3, 4, 10, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

Cordes, Charles

H., 10

Cordes, Charles

Henry, 15, 20, 21

Cordes, Fred,

19, 21

Cordes,

Frederick James, 19

Cordes, Grace,

19, 20, 21

Cordes, Henry,

3, 4, 8, 12, 13, 19, 20, 24

Cordes, Henry

George, 15

Cordes, John, 4,

8

Cordes, John

Henry, 3, 29

Cordes, Lizzie,

3, 4, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21, 29

Cordes, Lucy,

19, 20, 21

Cordes, Mynne,

13, 19, 20, 21

Cordes, Sylvia,

24

Cordes, William,

16, 18, 19, 21, 24

Crown King, 10,

13, 14, 25, 27

Earp [Virgil], 6

Eckerman, Miss,

19

Edwards, Mrs.

Eliza, 15

Ehrenberg, 13,

14

Elise, 3, 14, 15

Francis, Dan, 16

Gainesville

Hall, Georgia, 20

Gas station, 4,

10, 11, 12, 13

General store,

9, 11

General Store,

12

Gillett, 6, 7,

15, 24, 29

Gillett, Dan B.,

15

Glendale, 21

Golden Belt

Mine, 22

Goodwin, 14

Granite Creek, 6

Grasse, John, 6,

29

Gray, Harland,

16

Hayden, Charles

T., 15

Helm, George, 16

Henderson,

Harry, 16

Henry Cordes,

25, 26, 27

Hill Ranch, 20

Humboldt, 21, 25

Joe's Gulch, 16,

18

Joe's Spring, 18

John Henry, 3,

8, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

Kingman, 22

LeValley,

Alfred, 6

Los Angeles

Business College, 4, 20, 21

M. J. McAlister,

13

Mannsmann, Adam,

6

Maricopa, 15, 24

Mayer, 3, 9, 10,

19, 20, 21, 22, 25

Mayer, Joe, 9

McAlister, Jack,

6

Meritt,

Harriett, 19

Miami, 21, 24

Minten, Westphalia,

Germany, 14

Murphy's

Impossible Railroad, 4

Neubieber, 21

New River, 17

Page, 24

Parker, 19, 24

Parker Flat, 19

Peoria, 17

Perry, William

H., 16

Post Office, 3,

4, 8, 9, 11, 15, 16, 18, 22, 23

Powell, 13

Powell, William,

6

Prescott, 8, 9, 10,

13, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 23, 24

Prescott and

Eastern Railway, 17

Richinbar Mine,

9, 22

Saloon, 4, 9, 11

Santa Claus, 20

Santa Fe,

Prescott and Phoenix Railway, 8

schoolhouse, 9,

19, 21

Schrimpf, Elise,

14

Schrimpf, Elsie,

3

Schrimpf,

Johanna, 14

Scott, Guy, 3

Simonds, Gene,

27

sink a barrel,

16

Soleri, 24

Soleri, Paolo,

24

Spaulding

station, 6

Springerville,

24

Standard Oil, 26

Stanton, 15

Steinmetz, Joe,

16

Stoddard, 21

stompers, 17

store and

saloon, 8, 10

Swilling, Jack,

15

Taylor Grazing Act

of 1934, 22

Tempe, 18, 19,

21

Tempe Normal

School, 18, 19, 21

Tip Top, 7, 8,

15, 24

Tip Top mine, 15

Tip Top Mine, 8,

24

Townsend, 6

Turkey Creek, 9,

18, 21, 22

U. S. Department

of Agriculture inspectors, 21

Vulture Mine, 14

Ware, Carrie, 19

Wheaton, Dick,

25

White Mountains,

23

White, Newt, 3

Wickenburg, 13,

14, 22

Williams, 9, 16

Woolfolk, 16

World War I, 18

Wynne, Mr., 17

Yavapai County

Court House, 14

Yavapai County

schools, 20

Yuma Prison, 7

Photograph taken 2005 by: Neal Du Shane

Photographs by: Neal Du Shane

Photographs on this page by: Neal Du Shane

Photographs on page 37 & 39 were supplied by Cathy Cordes

Recreated from Glass Plate negatives by: Neal Du Shane

Compiled and edited by: Neal Du Shane 2006

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form

except for short quotation in critical essays and reviews.

APCRP Internet Presentation

All Rights Reserved, © 2007 APCRP

WebMaster Neal Du Shane