Internet Presentation

Version 052406

“Big

Dowser helps locate bodies in old cemeteries like

BCC's (

By Bruce Colbert

BB/CC News

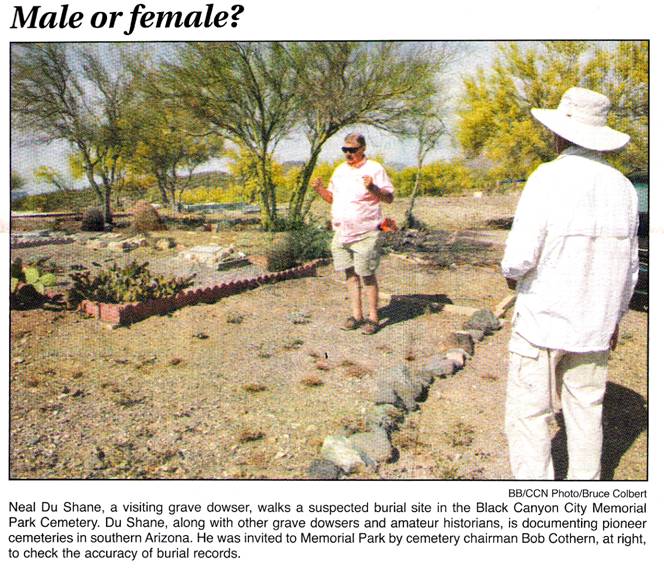

Call it the case of the missing bodies.

When Bob

Cothern became chairman of

"I had heard from people in town, that they thought there were people buried where there wasn't a headstone, and other people thought there were headstones for people who were buried elsewhere," Cothern said. "Besides digging, I didn't know how to find out if someone's there or not."

Enter Neal Du Shane. Du Shane is a grave dowser. Grave dowsing is like water dowsing only you dowse dead bodies instead of water.

Du Shane makes his dowsing rods out of straightened metal coat hangars. "The best scientific answer I can offer for why metal works and willow sticks don't is that the metal in the coat hangars reacts to the magnetic field of the body, the aura that apparently stays with the body even after it dies.

"People are skeptical, and believe me, I've been put to every test you can think of to try to disprove grave dowsing, but it works, and it's proven itself to be extremely accurate and reliable. I can't explain how it works, other than the fact that the rods react to the bodies' magnetic fields, I just know it does work."

Du Shane is a member of a devoted group of historians and amateur sleuths who dowse known or suspected pioneer cemeteries. The grave dowsers document their finds, or lack of them, and publish the results on Internet Web sites and "in scientific journals.

"The easy part is determining whether people are, or are not, buried some place," Du Shane said. "The hard part is finding out for sure who is' buried there. That's where the research comes in. If there isn't a headstone or family member who can vouch for the grave, we start the detective work."

Du Shane said scouring state and federal Office of Vital Statistics records, genealogies, census data, funeral announcements, family members and other sources often leads to a successful identification of an unmarked grave.

Before getting down to dowsing

"I really had my doubts about this working, but I guess it really does," Cothern said.

"I didn't know what to expect, but it's amazing to see that it actually works," Baker-Hans said.

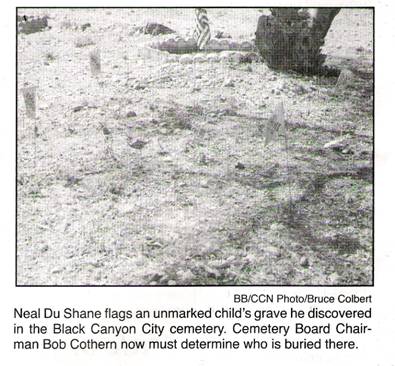

Du Shane can differentiate between male and female and adult and child gravesites; he cannot differentiate between human or animal remains. "The likelihood of someone digging into this hard, rocky ground to bury a dog or cat isn't very high. So I think we can safely assume all our finds are human," he said.

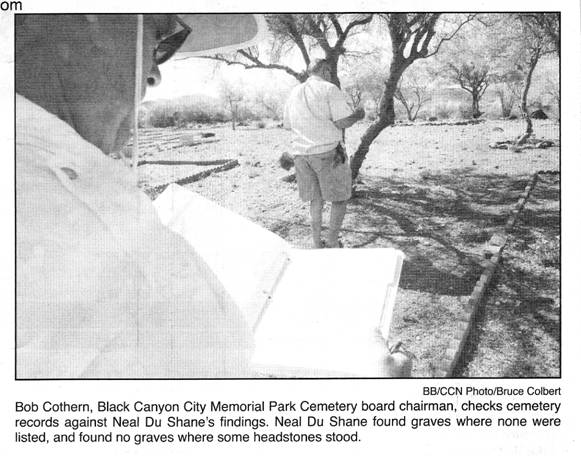

"According to my records, there

should be a woman, buried here," Cothern said pointing to a plot without a

headstone. To Cothern's dismay, Du Shane dowsed the spot and announced there is

an adult male buried there.

"According to my records, there

should be a woman, buried here," Cothern said pointing to a plot without a

headstone. To Cothern's dismay, Du Shane dowsed the spot and announced there is

an adult male buried there.

At another burial plot there is a headstone but no body is detected. Du Shane did locate a body about three feet to the side of the headstone, but who it is or why it is there is anybody's guess at this stage of the research.

"That happens," Du Shane said. "Sometimes the casket can shift while underground, and at other times, for whatever reason, the body is not buried at the headstone."

"That's probably very true up-here,'' Cothern said. “I know there are a lot of boulders underground here, and if they hit a boulder while digging a grave, they would just move to one side or the other and start digging again."

Du Shane's findings at several

graves in

"Well, I got some of the questions I wanted to know answered," Cothern said. "But now I've got even more questions than when we started about who's buried where."

"That's the way it goes sometimes," Du Shane said.

See related story on Page 9 for contact addresses and Web sites for Neal Du Shane.

Page

9 – Big Bug/Canyon Country News * May 24, 2006

Grave dowser takes a look beneath the surface

By Sue Tone – Prescott Valley Tribune – Photo’s by Sue Tone

Missing markers, disintegrating

wooden crosses and deep ravines from flooding in the 1960s have made it nearly

impossible to find the final resting places of

That's where Neal Du Shane and his grave dowsing rods come into play.

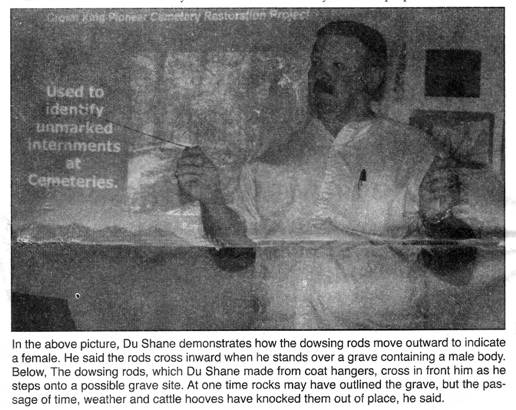

Du Shane spoke to a small group of Humboldt Historic Society members recently about what it takes to find unmarked graves.

He uses two coat hangers, which he cut and straightened to about 20-inches long with a 90-degree bend for 4-inch handles.

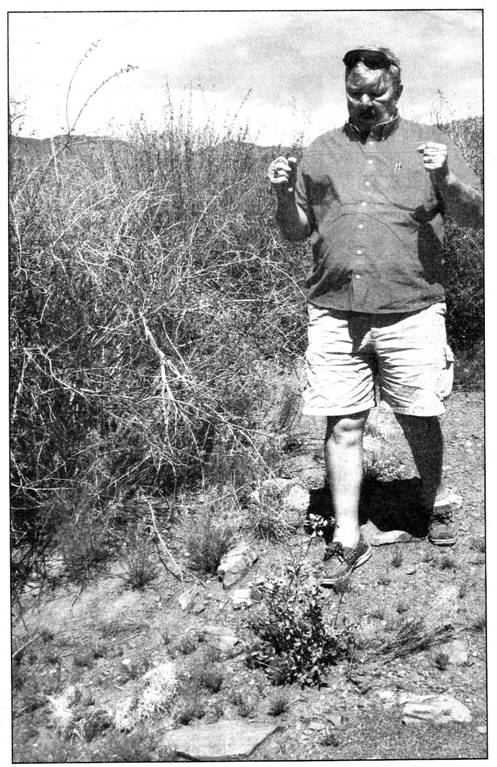

As he walked across the dirt and rocks of the high desert west of Humboldt, and held them out before him, he felt the rods turn inward and cross as he stepped onto a burial site. The rods uncrossed when he was clear of the body.

Du Shane said he learned that sometimes the rods opened wide, pointing outwards, and then returned to a parallel angle.

He learned that the outward swing indicates a female body, and the crossed rods connote a male body.

After dowsing the gravesite, he determines the size and will place four stakes with orange flags at the corners. Sometimes he outlines the grave with small, stones.

“I’ve found that about 90% of interments are laid out in an east-west configuration, with the head at the west end looking to the east. That seems to be a Christian tradition having to do with looking eastward to the Second Coming," Du Shane said. “Most burials are about 4 feet by 7 feet for a typical adult grave, smaller for teens and children”.

"Pretty soon, I'll begin to

see rows and see how the cemetery is laid out," he said.

"Pretty soon, I'll begin to

see rows and see how the cemetery is laid out," he said.

Unfortunately, when he finds a grave, that doesn't, mean that he can identify the buried person. If records aren't available and no living caretakers or family members remember such details, that information is often lost forever, Du Shane said.

The living still can offer their respect, however, by clearing, cleaning, and marking burial sites.

In response to a question about whether walking across a grave is disrespectful, Du Shane said, "I under- stand the reasoning, but that's the only way to detect them. I don't intentionally disrespect by crossing on top of the grave. Crossing over the grave is the only we can locate unidentified graves. I think people would understand that we're just trying to find loved ones."

The writing on some markers, whether in stone, marble, metal or wood, deteriorates over time. Du Shane uses several methods to increase legibility.

Du Shane sometimes wipes shaving cream on the face of grave-stones and photographs the dates and words. The whiteness stands out and sharpens the outlines of letters. Du Shane said he brings a lot of water to wash off the shaving cream, because the chemicals in it may hasten erosion.

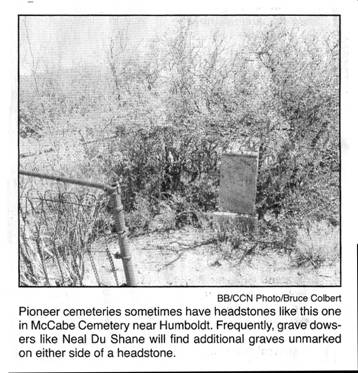

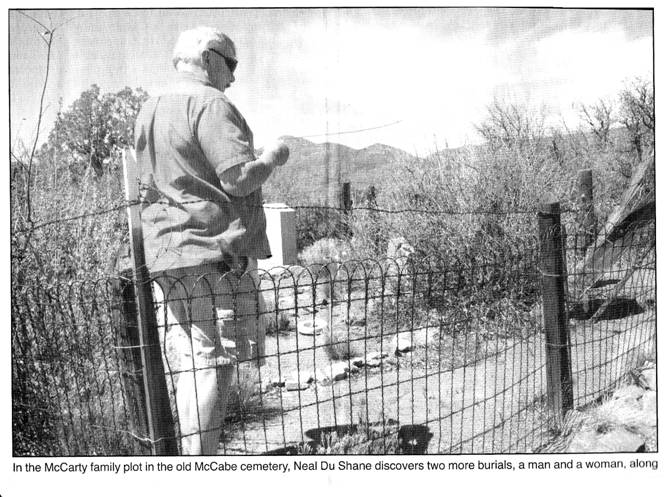

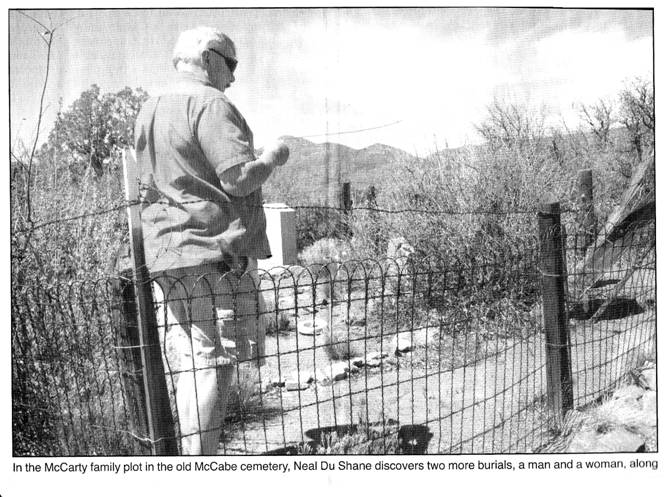

Within a small fenced area of the old McCabe cemetery, it is obvious someone from the family visits the site.

Faded plastic flowers lie scattered about, and chunks of quartz mark the outline of two large plots with headstones and a small cross sits between them.

Du Shane found five more bodies, a male and female lying head to toe along one fence line that, based on the size, could be children or young adults; a male buried near the cross between the marked plots; and a male lying crossways at the section near the gate.

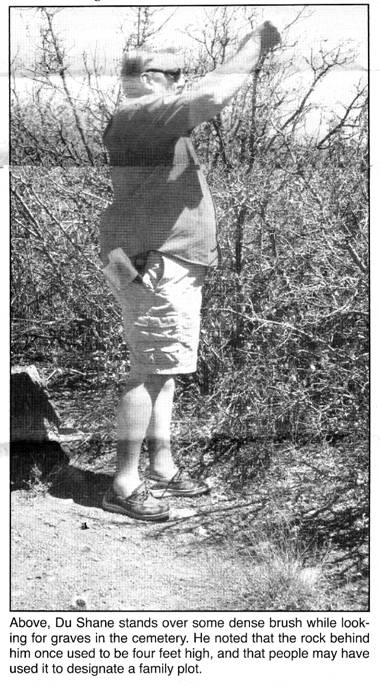

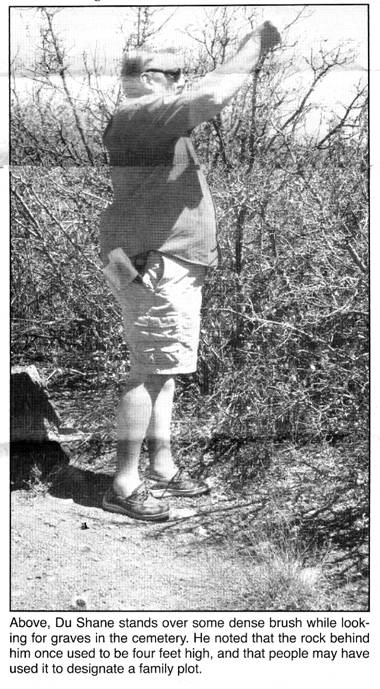

At a nearby two foot rock monument, Du Shane lifts the rods chest-high over brush to find another grave.

"The families out here were so poor that a lot of times they just planted a small bush as a headstone. If the brush were cleared away, we'd probably find another 20 sites right around this area."

Dowsing works because the metal rods detect the electromagnetic field left in bodies after death, he said. Disturbed earth does not cause the rods to cross, as some people believe, Du Shane said.

Someone once took him into a cemetery where two mounds of earth indicated recent interments. "I tested for burials and found that one contained a body and one did not," Du Shane said, adding that cemetery personnel-confirmed his findings.

Some people also use dowsing to locate water pipes, both metal or plastic. To distinguish between grave or pipe, Du Shane said he knows if it is pipe if it runs in a straight line for a distance.

If the rods indicate a rectangular shape, it is a grave.

Du Shane worked with the members of Crown King Historical Society this past year on the local cemetery.

He said up near the fence, the rows of graves are neatly laid out, with markers listing Hispanic names.

"The rest seems like they were

buried by a, hand grenade, all scattered about with no rhyme or reason,"

he said.

Some states offer financial help to organizations or volunteer groups to maintain the sites, he said.

"A cemetery is considered to

be a

In addition to the work at Crown

King, Du Shane has been busy locating grave sites at:

He has done extensive work in

Mitchell County, Iowa: Du Shane and his wife return to their home in

Those interested in learning more about preserving cemeteries: may visit the Web site www.apcrp.org

Page

12 – May 10, 2006 –

Grave dowser takes a look beneath the surface

By

Missing markers, disintegrating wooden

crosses, and deep ravines from flooding in the 1960s have made it nearly

impossible to find the final resting places of

That's where Neal Du Shane and his grave dowsing rods come into play.

Du Shane spoke to a small group of Humboldt Historic Society members this past week about what it takes to find unmarked graves.

He uses two coat hangers, which he cut and straightened to about 20-inches long with a 90-degree bend for 4-inch handles. As he walked across the dirt and rocks of the high desert west of Humboldt, and held them out before him, he felt the rods turn inward and cross as he stepped onto a burial site. The rods uncrossed when he was clear of the body.

Du Shane said he learned that sometimes the rods opened wide, pointing outwards, and then returned to a parallel angle.

He learned that the outward swing indicates a female body, and the crossed rods connote a male body.

After dowsing the gravesite, he determines the size and will place four stakes with orange flags at the corners.

Sometimes he outlines the grave with small stones.

"I've found that about 90 percent of interments are laid out in an east-west configuration, with the head at the west end looking to the east. That seems to be a Christian tradition having to do with looking eastward to the Second Coming," Du Shane said. Most burials are about 4 feet by 7 feet for a typical adult grave, smaller for teens and children.

"Pretty soon, I'll begin to see rows and see how the cemetery is laid out," he said.

Unfortunately, when he finds a

grave, that doesn't mean that he can identify the buried person. If records

aren't available and no living caretakers or family members remember such

details, that information is often lost forever, Du Shane said.

Unfortunately, when he finds a

grave, that doesn't mean that he can identify the buried person. If records

aren't available and no living caretakers or family members remember such

details, that information is often lost forever, Du Shane said.

The living still can offer their respect, however, by clearing, cleaning, and marking burial sites.

In response to a question about whether walking across a grave is disrespectful, Du Shane said, "I under- stand the reasoning, but that's the only way to detect them. I don't intentionally disrespect by crossing on top of the grave. Crossing over the grave is the only we can locate unidentified graves. I think people would understand that we're just trying to find loved ones."

The writing on some markers, whether in stone, marble, metal or wood, deteriorates over time. Du Shane uses several methods to increase legibility.

Du Shane sometimes wipes shaving cream on the face of gravestones and photographs the dates and words. The whiteness stands out and sharpens the outlines of letters. Du Shane said he brings a lot of water to wash off the shaving cream, because the chemicals in it may hasten erosion.

Within a small fenced area of the old McCabe cemetery, it is obvious someone from the family visits the site.

Faded plastic flowers lie scattered about, and chunks of quartz mark the outline of two large plots with headstones and a small cross sits between them.

Du Shane found five more bodies, a male and female lying head to toe along one fence line that, based on the size, could be children or young adults; a male buried near the cross between the marked plots; and a male lying crossways at the section near the gate.

At a nearby two-foot rock monument, Du Shane lifts the rods chest-high over brush to find another grave.

"The families out here were so poor that a lot of times they just planted a small bush as a headstone. If the brush were cleared away, we'd probably find another 20 sites right around this area."

Dowsing works because the metal rods detect the electromagnetic field left in bodies after death, he said. Disturbed earth does not cause the rods to cross, as some people believe, Du Shane said.

Someone once took him into a cemetery where two mounds of earth indicated recent interments.

"I tested for burials and found that one contained a body and one did not," Du Shane said, adding that cemetery personnel confirmed his findings.

Some people also use dowsing is to locate water pipes, both metal plastic. To distinguish between grave or pipe; Du Shane said he knows it is pipe if it runs in a straight line for a distance.

If the rods indicate a rectangular shape, it is a grave.

Du Shane worked with the members of Crown King Historical Society this past year on the local cemetery.

He said up near the fence, the rows of graves are neatly laid out, with markers listing Hispanic names.

"The rest seems like they were

buried by a hand grenade, all scattered about with no rhyme or reason,"

he said.

Some states offer financial help to organizations or volunteer groups to maintain the sites, he said.

"A cemetery is considered to

be a

In addition to the work at Crown

King, Du Shane has been busy locating grave sites at

He has done extensive work in

Mitchell County, Iowa. Du Shane and his wife return to their home in

Those interested in learning more about preserving cemeteries may visit the Web site www.savinggraves.org or www.rootsweb.com /-iamcpcrp/, www.apcrp.org

Internet Presentation

Version 052406

Reproduction approval courtesy: Bruce Colbert

Edited by: Neal Du Shane

WebMaster: Neal Du Shane

All Rights Reserved – © APCRP 2007