American Pioneer

& Cemetery Research

Project

Internet

presentation

Version 072813

Copyright © All Rights Reserved

PLACERITA

A Story of Men and Mining

Yavapai County, Arizona

By Kathy Block

APCRP Research Staff

Placerita is a historic mining settlement

located east of Kirkland, AZ and south of Wagoner Road near other areas

researched by APCRP, such as Walnut Grove and Wagoner. This little-known site

has an interesting history and is presently marked by one deteriorating stone

building, an old mine adit, and remains of a

processing mill.

The

terrain is thick chaparral vegetation that opens up to grassland. There are a number

of cattle ranches in the area and some leased BLM land used for grazing. As the

land becomes steeper heading into the edge of the Weaver Mountains, the brush

becomes even thicker. Elevations around Placerita are around 4,800 feet. There are numerous washes

and gulches nearby that were mined, dry washed and panned for gold and copper.

The

name “Placerita” came in with early miners from

California. It is a diminutive of “placer” in Spanish, which means the place

near a riverbank where gold dust is found and washed out. Usually less than 100

people lived there, although the 1910 census listed 172 residents, at its peak

in the active mining period from about 1880 to 1910. Only 30 people were there in 1905. Many

residents probably lived in tents, as was typical of early mining

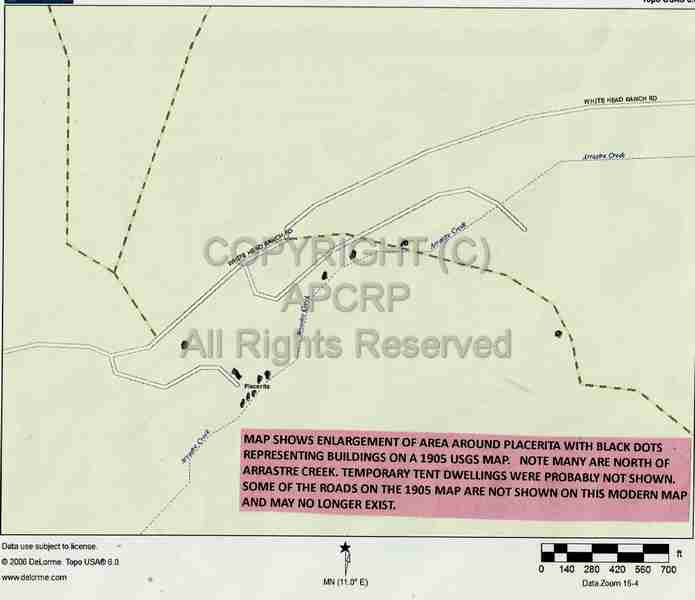

settlements. A 1905 USGS map indicated

five buildings on the north side of Arrastre Creek

clustered together, plus scattered buildings to the NE along the creek and a

few along the road to Placerita from Kirkland.

|

Former building locations at Placerita. Map by Neal Du Shane, text

overlay by Kathy Block |

|

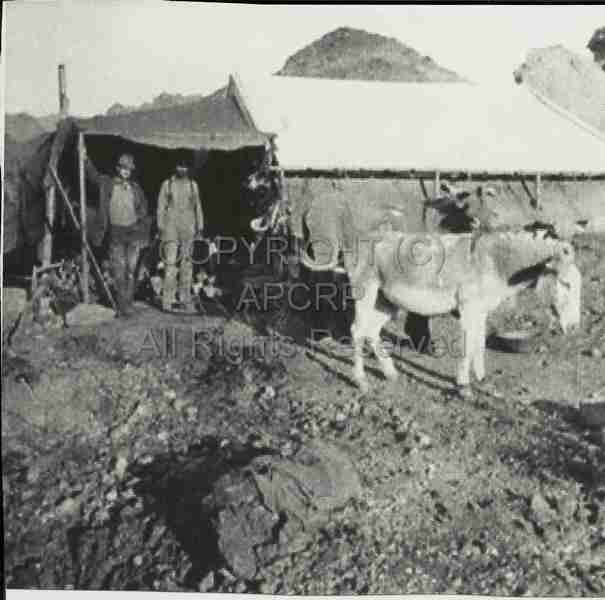

Typical miner's residence with

two burro’s. Photo Courtesy Mohave Museum of

History and Arts, Kingman, AZ |

In

ways, Placerita was an “Old West” town with some

murders, a range war between goat herders and sheep herders, and great

excitement over gold prospects, followed by decline as the mines played out.

Our

interest in Placerita was prompted by an article from

an old newspaper.( Note: Most of the newspapers quoted

in this article are from the Weekly Arizona Journal-Miner unless

otherwise stated.) There was the possibility of a cemetery or graves, commonly

found around old mining areas. The

article of August 01, 1906 read:

“DEATH SAID TO BE DUE TO

EXTREME HEAT

Eph Meador Expires At His Home

in Placerita

After

an illness of only a week, due, it is said, to the heat, Eph Meador died

yesterday morning at his home in Placerita.

The

deceased was a native of Illinois and about 54 years of age. He was unmarried,

and leaves two brothers surviving him both residents of the Walnut Grove

district.

A

casket in which to inter the remains was shipped by express last

evening to Kirkland by the Rufner undertaking

establishment on Cortez Street. The funeral will take place this afternoon from

the home of the deceased to the Kirkland Cemetery, where internment will

take place.”

Actually, Eph Meador was buried

in Walnut Grove Cemetery. His grave is marked by a flat brown stone with his

name chiseled out on top and on the bottom the words, “Died July 30, 1906.”

There is an upright wooden marker behind this stone. His sister Ophelia, his father Ambrose, and brother Louis are also buried at Walnut Grove Cemetery, located

about 5 miles to the East of Placerita.

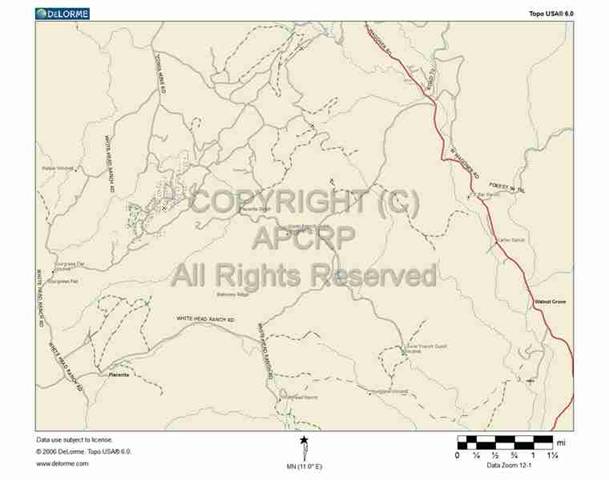

|

General area map of Placerita. Map by Neal Du Shane |

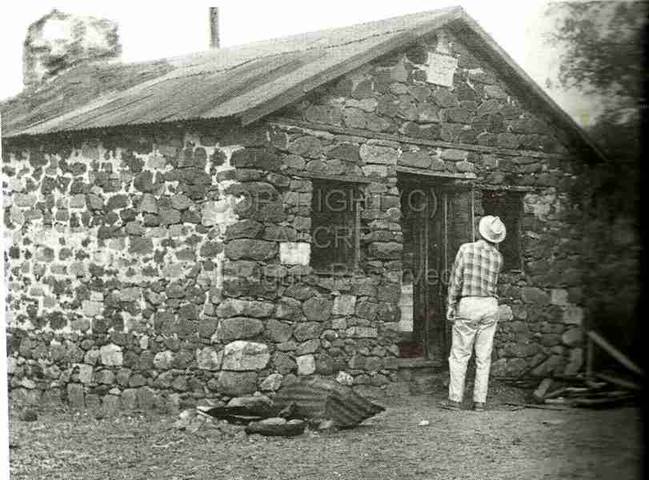

1950 stone structure. Photograph

reproduced with permission of Bill Fessler, American

Traveler's Press. |

|

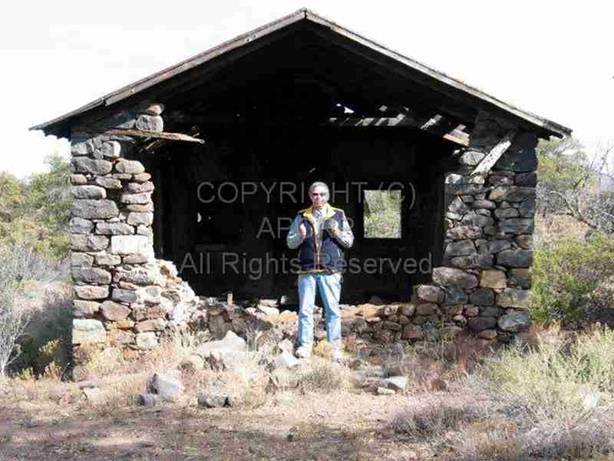

2008 - Gene Simonds

in front of structure. Photo courtesy Neal Du Shane |

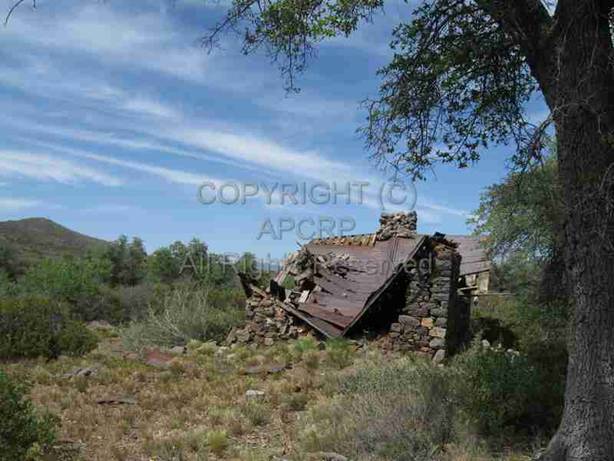

2013 - decay

in 5 years. Photo courtesy Ed Block |

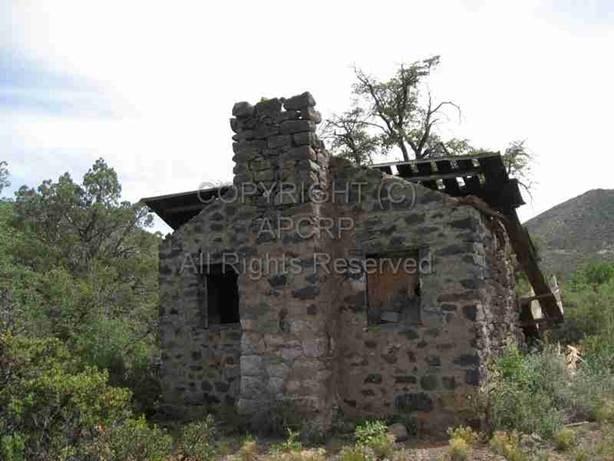

There

are various theories about the use of this building. Thelma Heatwole

in her book, “Ghost Towns and Historical Haunts in Arizona” (1991) said:

“A concrete marker above the front door reads 'Isabella-1875.' Whoever she was,

Isabella must have owned the most substantial house in town. It was the only

one still standing. Inside features were a fireplace and a floor with a trap

door.” (Written in the 1950s.)

Other

writers referred to the building as a “stone cabin”. It could have been related

to a mine.

A

Nov.10, 1909 news item said:

“R.E.

McGillen, interested in the Old Spaniard group of

mines in the Placerita section, makes the statement

that his company is preparing to resume development and the Isabella

claim system will be selected as the demonstrative point.”

|

Ed Block on trail to stone ruin.

Photo courtesy Kathy Block |

Area east of stone ruin. Photo

courtesy Ed Block |

There

were probably at least two roads to Placerita. A rough track off present-day Whitehead Ranch

Road that goes directly to the stone ruin is a walking path only. Another road

that can be driven goes down to a large open, flat area less than 1/2 mile east

of the stone ruin. This area may have

been the site of many buildings, and an old road goes west across a gulch to

the ruin. The main road to Placerita was probably

built around March 1900, though others probably existed prior to that time. In

1880 “Grizzley Callen” had

found small veins and opened a quartz mill, which must have required access.

The 1900 road “for steam traction wagons” being built by a New York and Ohio

Company of “unlimited capital” was “now being graded from People's Valley to Placeritas, for a 100 stamp mill on the property.

There

apparently were no stores in Placerita. Most

residents probably traveled the 15 miles NW to Kirkland or about 65 miles to Prescott

or Wagner for goods and services. By 1900 an old photo of Kirkland showed a

hotel, store, stage station, and mentioned a “safe” (maybe for miner's gold?). The

same commercial conveniences were offered at Wagoner, 11 miles to the east. A

1909 ad for a train from Kirkland to Phoenix listed a fare of $3.20 one-way,

from an Atchison and Santa Fe RR depot in Kirkland.

Mining

equipment could be ordered from a firm in San Francisco in 1888. Some stores in

Prescott advertised “eastern prices” for items such as clothing, buggy whips,

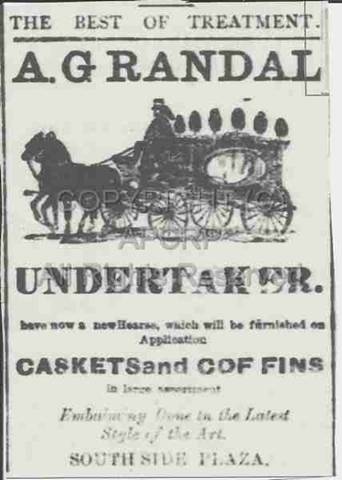

lumber, groceries, feed and grain. There were several undertakers in Prescott. Rufner Funeral Parlour was a

popular one.

|

1886 Undertakers Prescott, AZ ad.

Coffins were often shipped to Kirkland, AZ by train. |

There

were probably few children in Placerita, though some

miners did have families. The nearest

school was Walnut Grove, about 4 miles East, where

children could either walk, ride, or go in a wagon on a rough road. A photo

from 1896 showed 16 children and an older male teacher sporting a white goatee

and a woman standing beside him in front of a one-room schoolhouse. Another

photo, undated but probably about the same time, showed the same man by himself

with a class of 22 children.

The

road or roads to Placerita were steep and rocky and

tended to become muddy and needed regular repairs. In September 1909, the Office of the Board of

Supervisors of Yavapai County, Arizona Territory in Prescott,

authorized W.B. Wright to spend not exceeding $200 for repairs to the Kirkland-Placerita Road.

Again, in December 1909, one John Flanagan was authorized to spend the

sum of $50 in repairing the road between Kirkland and Placerita.

And in January, 1915, $10.05 was approved from the “expense fund” to one L.J. Haselfeld for “supplies for Kirkland to Placerita

Road.”

January

11, 1911, news article reported a new road being built at Placerita:

“GREAT ACTIVITY REPORTED AT PLACERITA. Arrivals from the camp of the Mines

Development Company, opening the McMahon and Zonia

mines, at Placerita, give an

interesting account of the progress of the work, saying that the camp is

teaming with activity, and has a healthy business look. Several new buildings

have been erected, and old ones remodeled and enlarged to meet increased

demand. A large force of men is employed in building a new wagon road up the

canyon from the main works, that the grade may be wide enough to accommodate

the wagons carrying the two large churn drills that are to be taken in from

Kirkland, for exploring the property. Considerable mine work is also under way

on the ground opened, and the belief is that the enterprise faces an attractive

future....”

As the

mines developed, five and ten stamp mills were built to process gold ore from

many claims at Placerita.

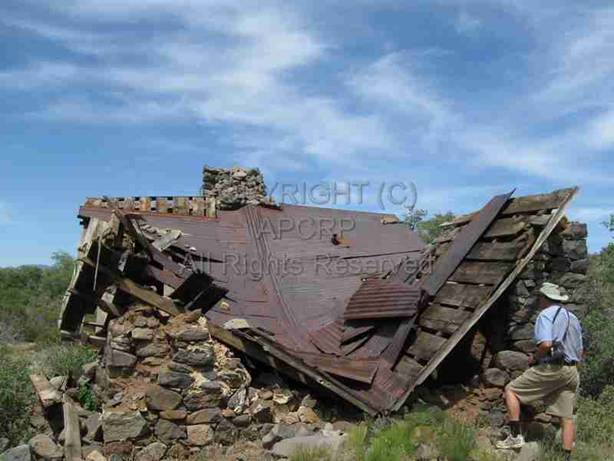

|

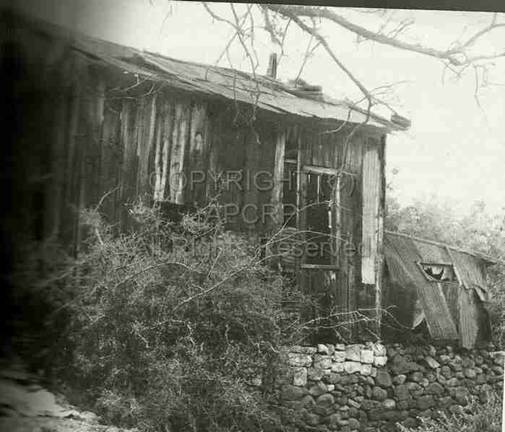

1950 – typical of mill house's

at Placerita. Reproduced with permission of Bill Fessler, American Traveler's Press. |

2013 - Remains of a mill site

at Placerita. Photo courtesy Ed Block |

One

gold ore processing mill was located at Whitehead Ranch Road near a road

heading south to Placerita. There are only a few

remnants left. There were actually a number of mills in the Placerita

area.

Mention

of two mills was made in an article November 02, 1895:

“The

Arizona & Illinois Construction Company has the most of its machinery for a

ten stamp mill on the ground at Placerita and expects

to have it up ready for operation within thirty days. The Isabella Mining Company

is also putting in a Huntington mill of ten tons capacity near the same place

and expects to have it in operation about the same time. Both companies have good claims there

although they are yet developed to any very great extent.”

Another

mill was proposed in 1900 at a property called the Navy group. The 10 stamp

mill would be built if the present ore values continued to a depth of 40

feet; the deepest cut was then 18 feet on a ledge 200 feet wide and 2 miles

long, worked by 15 men. One group of mining men pronounced it “a second mother

lode, like that of California.” The New York and Cincinnati capital group had

already purchased water rights and paid cash for over 700 acres of land in the

area! No later word on results.

An ad

in the Arizona Weekly-Journal, January 27, 1897 offered employment at Placerita:

“WANTED

- A first class millman to take charge of a ten stamp

mill.

Also must be able to make all necessary repairs. Address: The Placerita Co., Placerita, Arizona

Territory.”

In the

early 1900s, Placerita was the site of extensive

placer mining in Placerita Gulch and other rich

gold-bearing washes. The nearby ranches raised goats and cattle, and some

sheep.

A

murder in May 1907 highlighted tensions between goat herders and sheep herders.

On May 10, 1907 A.T.

Meadows died at his goat ranch after being shot in the groin by a

Mexican assailant who fired four shots at him. Meadows returned fire and with

“an unerring aim” managed to kill the shooter.

Meadows left behind a wife and 6 children “in poor circumstances.” The

incident aroused the Walnut Grove and Placerita

districts. The farmers and stockmen declared they would “assert their rights

and prevent further encroachments on their domain by the sheep herders, who are

said to show no respect for the rights of the old settlers of the

community.” Meadows may have been buried

in Walnut Grove Cemetery, but no records verify this.

Over a

year after the murders, an ad from the Arizona Republican, August 2,

1908, in a section called “Popular Wants” offered: “FOR SALE. 150 goats,

located at Placerita, 40 miles S.W. Of Prescott. Address: N.H. Scott, Mesa, Arizona.”

An

earlier murder took place in Placerita around August

6, 1895. According to a news report, a Mexican had been killed at Placerita by a “fellow country man,” around 10 PM, on a

Sunday night. The whole top of the Mexican's head was blown off. The other Mexican,

named Frederico Monje,

about age 32, who did the shooting, mounted a horse

and, with two other Mexicans, left the camp, saying he was heading towards

Prescott. Instead they rode towards Peeple's Valley.

A Justice William Peat from Walnut Grove held the inquest on the “remains of

the dead man” the next day. It was

assumed the murderers were “well on their way to the Mexican line.”

Placerita had a post office from February

1, 1896 to August 15, 1910. It may have

been in the stone building. There were a number of people who had managed the

post office. John W. Cool, a miner and merchant, was postmaster in 1903. Lottie

B. Mahard was appointed postmistress at Placerita in 1906, replacing Richard E. McGillen

who resigned.

|

Possible mill crane near entrance road to Placerita.

Photo courtesy Ed Block. |

In

November, 1901, it was announced that bids were being taken for the U.S. Mail

on “star routes”, as present contracts expired June 30, 1902.

The

service was fifteen miles from Kirkland to Placerita

and back, three times a week. Mining camps and all citizens residing along the

star route were served by a carrier bringing mails to various post offices

along the route. Also, the carrier was required to deliver mail into all boxes

and hang small bags or satchels, provided by the customer at their own expense,

containing mail, on cranes or posts the customer erected along the route! The

crane or box on the roadside had to be located in such a manner as to be

reached “as conveniently as possible” by the carrier without dismounting from

the vehicle or horse! If there was a lock attached to the box, a key was not to

be held by the carrier, as he was expected to deposit the mail without the

necessity of unlocking the box. The carrier “is not expected to collect mail

from the boxes, but there is no objection to his doing so if it does not

interfere with his making the schedule time.” The mail carrier “must be of

good character and of sufficient intelligence to properly handle and

deposit the mail along the routes.” In 1901, pay was $272.46 and in 1905 pay

was $550 – per year!

Placerita has an extensive history of

mining ventures. The earliest prospectors were probably Mexicans who took out

“free gold” as early as 1565. A gold rush began in the early 1880s with a

colorful miner named “Grizzley Callen”,

who found small veins of gold in the vicinity of Placerita

Gulch. Soon a small settlement arose

along Arrastra Creek and much placer mining was

done. Gulches dissected a

northeastward-sloping pediment of general elevation of less than 5,000 feet

above sea level. This pediment consists of granite, diorite, and steeply

dipping schist with gravel and lava. It

contains many small gold-bearing quartz veins. These eroded to furnish gold for

placers.

No

records or estimates of early production are available. A publication, Gold

Placers and Placering in Arizona, Bulletin 168,

by the Arizona Bureau of Mines, reprinted 1994, reports on gold mining in the Placerita area thru 1933. It reported that “in 1899 Blake

(an Arizona Territory geologist, in a report to the governor), stated that 'the

placers at Placerita have long been known and worked

and are regarded as good wage mines.” A small dredging project was attempted in

the early 1930s on a small area of ground in French Gulch about 1 mile below Zonia Mine. This was 20 years after peak mining activity.

During

the 1932 - 1933 season, when water was available,

about 25 men were placer mining in the vicinity of the junction of French and Placerita gulches, using rockers and sluices. Their average

daily earnings were about 50 cents per man! The total production prior to June

1933 was approximately $2,000. They found fairly coarse gold, with many $5 and

$10 nuggets and one $80 nugget. The

value of gold then was $18 per ounce. A large-scale operation with a one-yard

gasoline shovel, angle-iron riffles and a barrel amalgamator processed gravels

and boulders at the junction of Placerita gulch and

French gulch in June 1933. No report on

production.

Early

newspapers beginning in 1886 began mentioning Placerita,

mines, and gold. Some mines opened, only to close again, possibly due to poor

returns or financial difficulties.

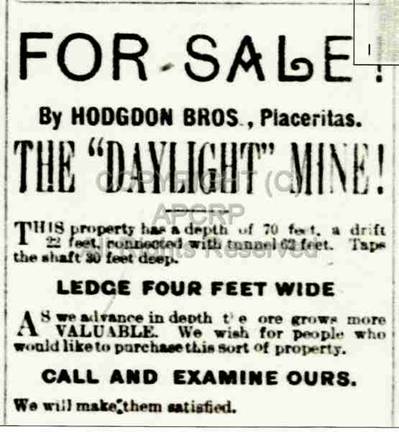

|

1898

Mine for sale, Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner, March 16, 1898 |

Typical

claim stake near Arrastre Creek. Photo courtesy

Kathy Block |

A sale

notice, on Feb. 8, 1899, read:

“Sam Hill vs the Placerita Co. Order of sale Bonanza Mine, machinery, etc. Walnut Grove District, $2,389.23. County

recorder's office reported by the Akers-Tritle-Brown

Abstracts.”

Used

mining machinery was available for sale as mines failed. Here's one ad from a

May, 1897, Prescott paper:

“MINING

MACHINERY FOR SALE:

A

Two

stamp mill-stamps 850lbs each, heavy battery and 8 to 10 horse power engine and

Perfection concentrator. Will be sold cheap and on reasonable

terms. Also a complete small steam hoist capable of

raising 500 feet. Perfectly new, never in use.

Will be sold for cash for less than it cost in Chicago....”

Some

news reports, though, were very optimistic. Note the sometimes exaggerated

language. These give a picture of what was happening in mining. Here are some

excerpts:

March

28, 1888: “The Great Placerita Country, in Walnut Grove District – One of the

richest and best portions of Yavapai couty is that

known as the 'Placerita' and comprises the western

portion of Walnut Grove mining district.... It is about ten miles in width and

fifteen in length, and it is everywhere interspersed with ledges of gold,

silver, copper and lead, and almost every ravine, gulch and canyon contains

heavy placer gold, and many of them are very rich. It is dotted all over with numerous springs

of pure crystal water....”“The placer mines have only been superficially

worked, and that by “dry washing” process, although even in that way more than

$100,000 has been taken out of the main Placerita

gulch in coarse gold, some of the pieces weighing over a pound, and one piece

containing $900.” (Gold was about $18 ounce or less then.)

November

15, 1899: “For several days we have heard rumors of a 'find' in the vicinity of

the Placerita country, but we could get nothing

tangible until today. The new discovery has been kept secret until it has been

demonstrated that the values exist, as claimed, and that the new discovery

located by those interested....But little work has been done upon this claim,

but enough was done to prove that the values are sufficiently high to warrant

the assertion that it is even a greater deposit than the great Alaska-Treadwell

mine in Alaska, where the ore only averages only about $2.50 per ton. On this

new discovery several samples of a 46-foot cut across the cleavage of the

schist shows an average of from $4 to $8 per ton. In other places averages of shafts and pits

show values of over $12 per ton.....”

The

January 26, 1904. Arizona Republican stated:

“BUSY

PLACERITA: Steady Work in Little Cripple Creek District and Vicinity.... Mr.

Green has started in to do some extensive mining on the President Mine,

situated in the lower end of Placerita (sometimes

called Little Cripple Creek).... the ore of which resembles the ore of the Gold

Coin mine of Cripple Creek... About 3 miles northwest of the President Mine on Arastra Creek, the owners of the Virginia Dale Mine are

taking out ore which they intend rolling at their 10-stamp mill farther up the

creek in the near future. This is one of the mines which D. Jones,,,,tried to bond before taking head of the Octave Mine.

He could not make satisfactory terms with the owners at that time, as the

showing was very flattering, and thereby Placerita

lost a great opportunity to become a 'live' mining camp....”

“The

Nagel group, which is west of the Placerita, is being

worked by one of its owners, C.C. McKene. The former

owner, Fred Nagel, caught the Klondike fever and left for Alaska. Before going he stopped and gutted all the

ore he could get at and the present owners have considerable dead work to do

before getting in shape to work profitably. It has hundreds of feet of work

done on it in the way of tunnels and cross-cuts and the writer has seen tons of ore from

this mine milled that placed in the neighborhood of $100 a ton.”

Mining

was dangerous, hard work, and accidents were frequent. Here's a report of an

April, 1908 accident: “Frank Hand, hurt by a cave at the mouth of the tunnel ten

days ago while engaged in timbering the tunnel entrance, is slowly recovering.

He was covered by several tons of falling earth and rocks. He was released from

his perilous position by his brother, George Hand, who feared at the time that

his brother would not be rescued alive. None of Fred's bones were broken in the

accident but he was crushed and badly bruised all over. He expects to be able to get out of bed in

the next ten days.”

One

month later, in May 6, 1908, report, Frank Hand had apparently recovered:

“Hand

Brothers are developing a promising ore body in the Rochester Mine in the Placerita district.....the paystreak

varies in thickness from one to three feet, the ore being of a good milling

grade. It is uncovered a distance of

fifty feet in a tunnel which is being run to tap a shaft at a depth of 100

feet, 200 feet further ahead. There are now 100 tons of ore on the dump ready

to be milled....The (Rochester) group is located one mile east of the Placerita post office....”

A

September 15, 1909 report enthused that:

“Along

the Hassayampa and at the Placerita

Gulch more men are at work placer mining at the present time than in years

past, and some big nuggets are being found at the latter place. It is

conservatively estimated at the present time that the total receipts per month

in this city of gold bullion and placer dust will run close to $75,000, several

small shippers sending in various sums.....”

Possibly

exaggerated news in a May 29, 1912 newspaper:

“BIG

GOLD NUGGET EXCITES PLACERITA.” The story described a gold nugget discovered

that weighed 23 pounds avoirdupois worth at least $2 per ounce, in the

aggregate of $2500....the nugget contained considerable quartz and a heavy

percentage of silver, hence the lower value....

A final

news item from July 18, 1917 almost 7 years after the post office closed in

August 1910, claimed:

“GETTING

LIVELY IN PLACERITA COUNTRY....Adding to the encouraging outlook is a gold

strike made a short time ago by Dud Meadows.

It was only surmised as to the values the samples would run to the ton,

but this feature was not weighed by the owner, who stated the discovery was out

of the ordinary and he feels very much pleased....”

|

Old Grizzly's Open Letter, not legible – (hype

selling his mining claims) |

Many of

these gold discoveries and mining developments were begun after a man named

Anson W. Cullen, known as “Old Grizzly,” traveled to Placerita

and “struck it rich” in July, 1884, while building a dam. He picked up about

$350 in gold. One piece was worth over $200. Then, in March, 1887, he found

gold worth $900, while completing a 5-mile ditch to his Placerita

camp, and was expected to start up his mill shortly.

Anson

Wilbur Callen had a varied life and career, in Placerita and other places.

He was born in New York State on May 11, 1832, and as a young man moved

to Junction City, Kansas with his wife, Catherine, born in 1835. They had nine

children. One son died at birth in 1878, another lived only 4 years, from 1872

to 1876. The family are all interred in Highland

Cemetery, Junction City, Kansas, with individual upright marble tombstones

marking their graves. The 1870 census lists him as a cattle dealer in Junction

City.

By

1875, Callen organized the Arizona Mining Company, in

Junction City. Pamphlets were printed that represented the Arizona Territory as

rich in mineral deposits and members, who were supposed to subscribe $500 each,

were recruited. Wagons and a general

outfit were procured and the party started for Arizona, arriving in Prescott

the latter part of October. An old 1875

photo shows about 40 people, mostly men, but a few women and children, riding

horses, or standing in front of a line of 14 covered wagons in downtown Junction

City. Three people sat on the roof of a two story brick and frame store

watching the action. The wagons seemed to mostly have teams of horses hitched

to them, but a few oxen/cows were visible.

The

party spent some time camping near Prescott when they arrived. Another member

of the party was elected manager, instead of Callen.

Some claimed that “misrepresentations” of the richness of the “mineral belt”

were made before any prospecting or exploration of the Placerita

area had been made. One disillusioned investor the next Spring

in April 1876, when a debate of the truthfulness of Callen's

statements was discussed in newspapers, proclaimed:

“I

do not blame Mr. Callen for any statement contained

in these resolutions, but I have heard of the height of imagination, and I

think the individual who drew up these resolutions stretched his ideas very

much, for his “mineral belt of Arizona” is the very width of imagination. I

would not notice these resolutions had I not been requested to do so by

citizens of Kansas now in Arizona. It is possible that these countries may turn

out to be good mining districts....When I say possible, I do not mean that the

prospect is any wise encouraging.”

Callen wrote a rebuttal in 1878 after

he returned to Junction City. He said it was his farewell shot and that he will

hereafter “leave Arizona and her affairs to take care of themselves until he

gets ready to start back to Prescott, and that when that time comes he will not

ask the advice of anybody about the propriety of his going. In the meantime if he owes anybody anything,

let them send in their bills.”

Near

the end of his letter to the newspaper in Prescott from Kansas, his irritation

came forth: “I am yet alive, and do not shrink from meeting any man face to

face. Am asking no

special favors. Am continuing to pay my own way. Am acting

on my own judgment. Am poor but independent as ever and shall not especially

bother myself about how many are exercising their minds over my affairs and

doings.”

By

1880, Callen, now referred to in news as “Old

Grizzly,” maybe due to what seems to be a feisty temperament, (though he was

only 47 years old), had found some gold and rich veins. He opened a quartz

mill. His son, James S. Callen (1861-1929),

apparently joined him at his claims. His

other children and wife apparently stayed behind in Kansas, and he made

frequent trips there by train to see them. Train passengers were often listed

in Prescott newspapers.

Tragedy struck in July 24, 1889.

Many such incidents happened in mining camps.

A headline screamed:

“IN SELF DEFENSE

Two Miners Shot and Instantly

Killed by A.W. Callen at His Camp.”

A news

reporter visited Callen in the county jail where he'd

given himself up to famed sheriff Bucky O'Neill and been transported to

Prescott, a 65 mile trip from his camp.

There, Callen “declined to make any statement

further than to allege justification in the killings, stating there were

witnesses to it and he preferred to await the preliminary examination, when all

the facts and circumstances would be brought out.”

Briefly,

two of Callen's friends, Byron J. Charles and Frank

H. Work had been at work at their claim near Callen's

claim. The two men walked to nearby Callen's cabin

and a dispute arose over a claim. Frank Work allegedly threatened to “do Callen up” unless Callen signed a

deed to a piece of mining property. They told him to get his pen and paper and

make out the deed. Callen refused and Charles may

have told Work, “We can't do anything with this old S.O.B, let's go.” Callen turned to see if Charles was armed and was hit by

him with a club across the neck. Callen went to his room, got the shotgun, and confronted

the men outside his house.

Byron

Charles was armed with a six-shooter and Callen had a

double barreled shotgun loaded with buckshot. Witnesses said Charles fired two

shots at Callen with the pistol within 20 feet of Callen's house, hitting a window and door frame. Charles

supposedly said to Work, “You have always been my friend and I'll stand by

you.” A housekeeper heard the shots and heard another man yell, “They're going

to kill Callen.” But, Callen

fired back at both men with the shotgun, killing them.

Judge

Ward was summoned from Walnut Grove to hold an inquest. Before the judge could

arrive, the bodies were “coffined and buried without an inquest.” (Maybe due to the July heat? I could find no information on

these burials or their final disposition.) The 1870 Census listed a Byron J.

Charles, age 16, born in New York, living in San Diego; in 1880 Byron J.

Charles, age 26, harness maker, lived in Pinal County, Arizona. The 1870 census listed a Frank H. Work, age

13, born in Maine, living in Pixmont, Maine. These

may possibly be the two men whom Callen killed?

At the

county jail in Prescott, Callen was released on

$2,500 bail, and Judge Fleury stated that while he

was justified in releasing Callen, an investigation

by a grand jury should be held. The jury

found Callen had acted in self-defense.

Callen's son Jim S. Callen

of San Diego arrived on the train to help his father. The local paper reported

that:

“His

father, with a number of friends, drove down in a barouche to the depot to meet

the talented young lawyer. The meeting between father and son is said to have

been very affecting.”

In

September 5, 1906, Callen lost his mines, after his

company failed. His son Jim had attempted to take over the properties, but was

unable to raise enough money to keep them going. Callen

published a touching notice in several papers. It was titled, “Old Grizzly's

Letter”: “Old Grizzly Talks for Arizona's and Especially Placerita's

Mines in an Open Letter to Mine Investors, Creditors, Prospectors and Miners.”

In it, he lists his various properties, including his Bonanza Cabin on Arrastra Creek, for sale, and gave up his claims.

Anson

Wilbur Callen died February 14, 1916 in Junction

City, Kansas, and is buried with other family members (including his wife who

had died in 1911) in Highland Cemetery, Junction City, Kansas.

According

to the family, “at least twice in his life he was a millionaire, but he spent

it as quickly as he earned it.

He had a great interest in fine jewelry and after each strike he had fabulous pieces

of jewelry made.” He gave his daughter Ella a gold watch with the inscription:

“A.W. Callen to his daughter E.E. Callen

on the 16th anniversary of her birth April 19, 1886.” His son Jacob received the watch chain

inscribed: “To J.B. Callen on the 27th

anniversary of his birth with love from his father “Old Grizzly,” Junction

City, Kansas, September 22, 1885.” (Reference 1.)

Legendary

“Bucky” (William Owen) O'Neill (1860-1898) had applied for the job of Assistant

Paymaster of the U.S.Navy, but due to a delay in the

appointment, he went to Arizona and edited a newspaper called “Hoof and Horn”

(a cattleman's paper in Phoenix.) He became a Judge for Yavapai County and was then elected

Sheriff for three consecutive terms. He and a deputy came to Placerita to take Callen to jail

in Prescott. “Bucky” was famous for his

“courage and fearlessness” and considered the best armed man in the Territory

and the best shot in 5 fights with 6 shooters.

He was killed in action in the Spanish American War with the Rough

Riders on July 1, 1898. His nickname came from his tendency to “buck the tiger”

- play contrary to odds at faro or other card games. He is buried at Arlington

National Cemetery. In September 1907 a monument was erected to him in Prescott

Courthouse Plaza. A sculpture by Solon

Borglum shows O'Neill on a horse, and a plaque details his accomplishments in

Arizona.

In

reaction to various killings and lawless incidents at Placerita

and the surrounding areas, an attempt was made to make Placerita

“dry” in August 1909. Residents of the area voted on enforcing prohibition in a

zone including Kirkland, Peeples Valley, Zonia Mining Camp, and Placerita.

The basis was the reopening of a saloon at Kirkland. There was supposedly “unanimous sentiment

among the men, women, and children to wipe out the liquor business.” The “dry zone” would have encompassed a strip

of country approximately 60 miles long by from 10 to 15 miles wide. The voters passed the law by a narrow margin.

The enforcement of the law, as allowed by Arizona at the time, could have taken

two years, but soon the law was repealed.

Today,

there is little commercial mining at Placerita,

except for a copper mining effort at Zonia Mine, by a

Canadian group, Alliance Mining Corp. In 2011 the company did an “airborne”

geophysical survey of Placerita South claims adjacent

to the Zonia Mine. They will use this data to begin

drilling in quartz veins. Some of the areas are historic mines.

Recreational

prospectors drywash and,

when there is water in the creeks, pan for placer gold, in the once thriving

area of Placerita. Except for the stone ruin, an old

mine adit, and scattered remains of an old mill and a

few pieces of rusty metal, nothing much remains to show the history of this

“Old West” mining settlement.

How to

locate Placerita.

Keep in mind that some of the roads go thru private cattle grazing areas

and ranch land. Stay on the main roads and honor any gates (keep them open or

closed as you find them.) Please do not litter or trespass, so these roads will

stay open to the public.

Go east

on Wagoner Road, signed to Walnut Grove, from Highway 89 between Yarnell to the south and Prescott to the north. After about

3.3 miles, at the top of a hill, turn south on Zonia

Mine Road (signed). Go about 1.5 miles

and continue straight on Whitehead Ranch Road at a junction. (Zonia mine road branches off on the right.) Travel about

5.5 miles on the Ranch Road to a junction. The Ranch road goes to the

right. Take this and go about .5 mile, looking for the stone ruin on your right. You will see

an overgrown, rough track leading down a hill to the ruin. If you go another .5 mile, you will find a

good track that leads to the right to a large camping area. Take this short

road down and walk or drive back along the creek bed to your right about ¼ mile to the end of an old road. Cross the creek and walk

about 100 feet on a faint trail to the ruin. If you miss the turn-off, a locked

gate and active mine are about 1 mile further on Whitehead Ranch Road.

Enjoy

this ghost town site, take nothing but photos, leave

nothing but footprints! The site is currently on Forest Service land.

|

2013 Ed Block - collapsed roof,

stone house ruin. Photo by Kathy Block |

2008 stone house interior

before roof collapsed. Photo by Neal Du Shane |

|

2013 - Collapsed wall. Photo by

Ed Block |

2013 - Chimney on back of ruin.

Photo by Ed Block |

|

Ed Block examines ruins of

stone cabin/house. Photo by Kathy Block |

2013 - Rocks using mud as mortar

in stone cabin walls. Photo by Ed Block |

CREDITS:

Neal

DuShane - maps, photos, and editing.

Ed

Block - locating, driving, photograph, and research Placerita.

Bill Fessler - American Travelers Press, permission to use two

photos from the book, “Ghost Towns and Historic Haunts” by the late

Thelma Heatwole, 1991.

Kay Ellermann – Librarian, Mohave Museum of History and Arts,

for photo of miner's tent camp with burro.

Internet

site: historywired.com: A Few of our Favorite Things. Smithsonian

Institution. Information about the watch and chain.

Historic

newspapers are found on the internet site: http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/.

American Pioneer

& Cemetery Research

Project

Internet

presentation

Version 072813

WebMaster: Neal Du Shane

Copyright

© 2013 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this website

may be used

for personal family history purposes, but not for

financial profit or gain.

All contents of this website are willed to the

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project (APCRP).