HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS

American Pioneer

& Cemetery Research

Project

Internet Publication

Version

101909-KB

NATIVE AMERICAN AND SPANISH GRAVES IN ARIZONA

By

Kathy Block

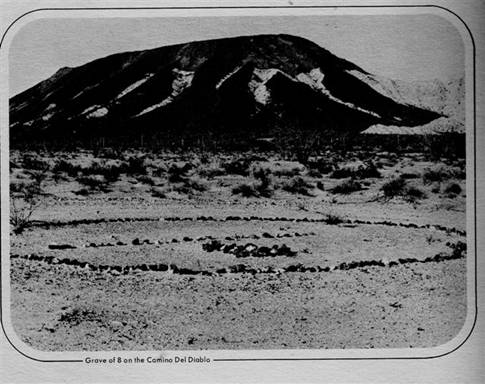

Grave of 8 people along the

Devil's Highway, AZ.

The

above 1971 photo, of a grave for eight people along the El Camino del Diablo

(Devil's Highway), sparked interest in researching information about Native

American and Spanish graves in Arizona.

In

various anthropological and archeological writings there is much information

about the burial customs of Native American tribes in Arizona, clues to what

possible grave sites might look like, and where they could be found. Practices

in different cultural periods varied from cremation, to burial in the ground,

caves, or pueblo sites.

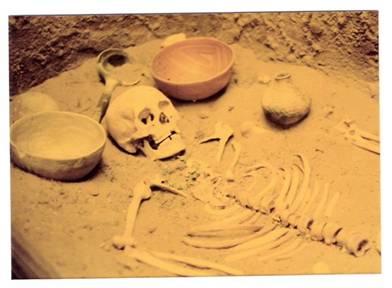

“Indian Princess” Skeleton

Displays

of skeletal remains and objects found with them in Native American graves used

to be fairly widespread in museums, visitor centers at national parks and

monuments in the Southwest. (The “Indian Princess” with her jewelry and objects found in her

grave was photographed in 1982 at the Anasazi Indian

Village State Historical Monument near Capitol Reef, Utah.)

Archeological excavations of prehistoric sites, notably in areas around Apache

County, Maricopa County, and southern Arizona yielded skeletons and artifacts

that were then deposited in many museums, especially during the 1950s and

1960s. Some two million remains of Native Americans are estimated to be

currently held in museums, government agencies, and private collections –

nearly as many as the population of Native people alive today, according to a

1998 Internet publication, “Coming Home-the Return of the Ancestors” by Claire

Ferrell. In 1868 the taking of Indian

body parts became official federal policy with the Surgeon General's order.

These remains, mostly 4000 heads taken from battlefields, burial grounds, etc,

were sent to various institutions for study. The Smithsonian had a collection

of almost 18,500 “ancestral remains.” Ferrell claims that the desecration of

Native American graves began with the landing of the very first Pilgrim exploring

party, which dug up a grave in 1620 and robbed it of its burial goods! (I was

unable to verify this claim.)

At

present, although U.S. Law and 43 states have laws protecting unmarked burials

and grave sites, removal of remains is still allowed for highway expansion,

golf courses, recreation areas, and from private lands, usually for reburial

elsewhere. Native Americans weren't legally declared “persons” until 1879, and

not granted citizenship until 1924, so were unable to protest grave site excavation

and desecration. To assist in somewhat rectifying past practices and provide

for respectful treatment of Native American graves today and in the future, the

Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act was passed in 1990. One

of the sponsors was Arizona's Senator John McCain.

Very

briefly, this act directs museums and other institutions to: (1) Increase

protection for Native American graves and provide for the disposition of

culturally affiliated remains inadvertently discovered on tribal and federal

lands; (2) Prohibit traffic in Native American ancestral remains; (3) Require

federal museums and institutions to inventory their collection of Native

American ancestral remains and burial goods within five years and repatriate

them to culturally affiliated tribes upon request; and (4) Require museums to

provide summaries of their collections of Native American sacred objects and

cultural patrimony within three years and repatriate them if it is demonstrated

that the museum does not have the right of possession.

On the

Internet there are now numerous Federal Register notices under “Native American

Graves Protection and Repatriation Act”. These notices list objects and remains

found in various archeological sites and tribes that might be eligible to

receive them. The notice gives details of when and where they were taken, what

their archeological and anthropological characteristics suggest for cultural

group of origin, and what present day Native American tribes were notified to

meet and discuss possible repatriation of these items. Here's a typical

example, edited for length.

Federal

Register.

Vol.73, No.46, Thursday, March 6, 2008. Notices. “In 1964, human remains representing a minimum of

14 individuals were removed from the Fortified Hill Site, Maricopa County, AZ, during legally authorized excavations conducted by the

Univ. of AZ . . . the human remains were accessioned into the collection of the

Arizona State Museum in 1964.

No

known individuals were identified. (There were 734 associated funerary objects

listed, including bones, beads, ceramic bowls and jars, shells, crystals,

textile fragments, projectile points, and one wood artifact.) “The ceramic

assemblage at the Fortified Hill Site suggests Archeological tradition . . . an

occupation between AD 1200 - 1273. Characteristics of

the mortuary program including cremation, placement within a ceramic vessel,

and the types of associated objects, are also consistent with the Hohokam Archeological traditions. The human remains are determined to be Native

American based on the archeological context . . . ” (Eventually

the museum staff met with representatives of the AkChin

Indian Community of the Maricopa Indian Reservation and other Native American

tribes to determine repatriation of return of the bones and artifacts to a

tribe or tribes.)

There

has been considerable controversy over meeting provisions of the Act. What

should be returned and what can be kept for scientific study? Who should

receive the objects and remains? Native Americans have gone to museums and

demanded return of “sacred objects”, and private collectors and dealers have

been scrutinized, as in a recent case involving 28 people arrested in the

southwest for artifact theft, etc. The on-going struggles, for example, over

the Kennewick Man's remains, found along the Columbia River in Washington State

in 1996, are discussed in several books. One, Ancient Encounters: Kennewick

Man and the First Americans by James C. Chatters, Simon & Schuster,

2001, explores this controversy. As one of the forensic anthropologists working

to study these remains, he has found strong evidence the remains are not Native

American. Despite this, tribes are fighting to reclaim them. One statement he

makes is:

“As strongly as I believe that it is

morally wrong to excavate recent (as in 1,000 to 2,000 years old), American

Indian graves or to keep them in museums without the consent and participation

of their cultural next of kin, I believe it is immoral to turn the bones of the

most ancient Americans over to modern tribes, who have expressed an intent to

bury them without learning what stories they have to tell about themselves and

their time.” (Page 269).

American Indian Graves, Happy

Camp. CA

Reading

the Federal Register notices offers clues to various burial practices and where

graves were found. Especially in Apache County and areas where Native Americans

were most established in prehistoric and more historic eras, as along the Gila

and Salt Rivers, remains were found buried under piles of stone or mounds, or

sometimes in caves (a famous site was Ventana Cave in

Pima County). In the case of cremations ashes were often placed in containers

and buried near villages or homes, with special objects (such as those listed

above from the Fortified Hill Site). Some cultures had cremations and

inhumations (intact burials) grouped in areas that appeared to have been used

for burial purposes only. There were various developmental periods of Hohokam cultures, with characteristic burials in each.

Details can easily be found in anthropological and archeological texts, and

won't be elaborated upon here. A modern-day person who

finds piles of stones suggesting graves, or objects in a remote cave, may

reasonably assume there may be a Native American grave site, if in an area

known to have been occupied by Native Americans. A rough indicator of age is the fact that in

prehistoric times the graves were generally placed without regard to uniformity

of direction. When uniformity is found, it is generally an indication of

comparatively modern internments.

Burial

practices varied greatly in the Southwest from tribe to tribe. The Apaches, for

example, had elaborate rituals. A book on the Internet, “Life Among the Apaches as Observed by John C. Cremory,

1868,” gave his observations. Briefly, Apaches at that time abhorred cremation.

They generally buried their dead at night, with stones on the grave to prevent

wolves and coyotes from digging them up. The burial was as far away as possible

from the village, either in a hole in the ground or rock crevice. They feared ghosts of the dead, and burned or

destroyed personal belongings of the dead or placed them in the grave, to

prevent “strange disease” (maybe smallpox?) They would never approach graves,

and anyone who did was considered a witch! The wickiup

was also burned, as nobody would live in it again. The Yavapai had similar

beliefs at this time. The Yuma on the

Colorado River practiced cremation. A jet boat tour guide told us that all

belongings were also destroyed so that, according to him, there would be no

inheritance conflicts!

Burial cave near Globe, Arizona.

A

cautionary tale here! A friend and another man found this remote cave on the

east side of Roosevelt Lake, near Globe, Arizona. The other man removed a

basket with a mummified baby in it, woven fiber sandals, pottery, etc.

Eventually he was caught and received heavy fines and some prison time! Our

friend had to testify against him. A sad situation.

Moral: Don't disturb any graves or artifacts you may find! There is also a

Federal Antiquities Law that may be enforced for removing objects over 50 years

old. This sign, found at the site of Signal, Arizona, is typical.

Sign at Signal

Native

Americans may sometimes remove remains from graves. A site, Native

American Netroots. Net. claims that the remains of Geronimo (referred to as Goyathlay) were secretly removed to Arizona after he died

of pneumonia in Fort Sill, Oklahoma in 1918. A Native American wrote on this

site:

An elder told me that the Navajo took

Geronimo's bones

and gave them a

proper burial place before the U.S. Army

only thought that

he remained buried at Fort Sill after

they buried him

there. I told her I had been to the grave

site. She asked

me, “Did it feel like he was in there?” “No,”

I said. “They 'buried' him in the grave

stone by stone, so

he wouldn't ever

come back.” she said. I personally don't

believe he is at

Fort Sill, and I don't believe this either.

A later

note states:

A look around the cemetery reveals the

possibility of that

being true, due

to the remoteness and seclusion of the area.

Note that there was probably more tree

cover nearly a

century ago.

A legend still persists that not long

afterward (his death) his

bones were

secretly removed and taken somewhere to the

Southwest. (From Dee Brown, Bury my Heart at Wounded

Knee, page 412.)

Most

Native American graves and Spanish graves of the 19th century on

into the present are found in cemeteries. A count on the Find-A-Grave site

showed at least 91 cemeteries scattered thru all the Arizona counties with

names that suggested Native American or Spanish use. Examples are: Navajo

Family Burial Cemetery in Cochise County; Hopi Indian Cemetery at Tuba City in Cococino County; Bighorse Family

Plot in Graham County; The Mexicano Cemetery in

Clifton, Greenlee County, which had five graves, all of which were infants; The

PeePosh cemetery in Maricopa County; and two Piute

Tribal Cemeteries in Mohave County at Kaibab and Moccasin.

Single grave at Happy Camp, CA

Here is

one Native American grave and a few others in a small, rundown cemetery at

Ferry Point, west of Happy Camp in Northern California. There is a road to the

Klamath River and Ferry Bar from the bluff where these graves are located.

Notice the turquoise bracelet and pile of rope by the grave of a 25-year-old

man who died in 1993. Was he a cowhand? A rodeo rider?

A feather (possibly eagle) hung on a branch above. This appears to be a family

cemetery, with many unmarked graves. A sign asks people to be “respectful of

the graves”, but a sagging iron fence with a gate hanging on one hinge encloses

the area. There are signs of vandalism, maybe from people or from bears (which

frequent this area). The Karouk tribe,

who live near Happy Camp, close this site and a stretch of river below every

August for ceremonies.

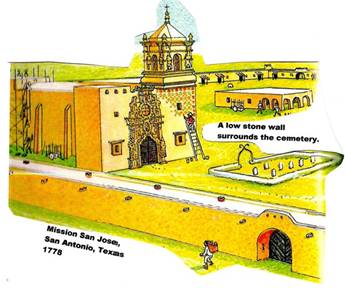

Typical mission church with

cemetery, 1778

Historically,

Native Americans and Spanish immigrants often intermarried, as people migrated

northward from Mexico and Central America.

The Pascuayaqui Tribe, of southern Arizona and

northern Sonora, Mexico has an intriguing project, called Mission 2000, thru Tumacacori National Historic Park. An accessible data base from Spanish mission

records of baptisms, marriages, and burials from the late 17th to

mid-19th centuries has been computerized. As of May 2005 it

contained nearly 8,090 events, over 22,031 people and their known information.

The ethnicity of names include various Native American

tribes such as O'odham, Yaqui, Apache, Seri, Opata,

Yuma, Mexican, Spanish, and various other European groups. This site gives an interesting version of how

“Arizona” got its name. A Yaqui prospector living in 1736 at Agua Caliente

discovered some extremely large pieces of nearly pure silver in the mountains

about half way between there and Nogales, Arizona. The discovery, known as “Planchas de Plata Canyon” became associated with a nearby

ranch called.....”Arizona”!!!

|

|

|

Cemetery at Tumacacori

There

are a few descriptions of cemeteries on the Internet that mention cemeteries at

the Spanish missions, which were established by Spanish Franciscan priests and

missionaries throughout the southwest to convert the Indians to Christianity,

and turn them into “productive” Spanish subjects whose toil would enrich and

enlarge the Spanish Empire. Indian neophytes were instructed in Catholicism,

the Spanish language and customs, farming, and simple handicrafts. In spite of

resistance and shirking of work, runaways, and even revolts, missionaries

created cohesive, self-supporting communities in the late 1700s.

An

account.

“The Early Spanish Missionaries”, The Resources of Arizona by Patrick

Hamilton, published in 1881 in Prescott, “under the authority of the

legislature” mentions San Xavier de Bac, nine miles

south of Tucson. He wrote that on the west side of the church was an enclosure

and a small chapel, which was formerly used as a cemetery. Bodies were kept in the chapel until the

ceremony of burial was performed. This

was the most important mission in the Territory, established in 1694. Papago Indians who resided at the mission preserved it from

destruction by Apaches in 1827.

Tumacacori National Historic Park is three

miles below Tubac on the Santa Cruz River. The

original mission was destroyed by the Apaches in 1826 and the occupants

massacred. Much has now been restored.

The above photos show the Soto marker, which identifies several graves

belonging to members of a family who lived at Tumacacori

in early 1900. The marked graves in this cemetery are from the late 19th

and early 20th centuries. Evidence of mission-era graves was

destroyed long ago by “weather, treasure hunters, and cattle.” Toward the end of the 19th century

the cemetery was used as a corral during cattle drives and roundups! Families

who moved into the area around 1900 knew it was holy ground, “campo santo” , and used it again as a

cemetery. The last burial was Juanita Alegria in 1916

- the only one that has been identified. Dead from the mission era are also

here. Between 1746 and 1825, there were 637 burials recorded. Forty-two burials

were registered by Father Ramon Libeross between 1822

and 1825 in the “new cemetery”. Record of a Pima child, named Maria Teresa

Gonzalez, age five, was the first. This shows use by Native Americans of

mission cemeteries. Some of the dead were killed by Apache raids or smallpox

and measles epidemics. Records from 1826 to 1848 when Tumacacori

was abandoned have never been found!

One

final mission is Mission San Augustin, a site known

as Tucson's birthplace, which is being restored. The project is heavily

dependent not just on archeological finds, photographs and documents, but also

on conjecture. The mission was built in the 1770s and had a convento,

two cemeteries, a granary, and other smaller structures contained in a compound

wall. The site had a much earlier history. Archeologists uncovered American

Indian pit houses, storage pits, and other features that date to 4000 years

ago. The site was already deteriorating by 1798 and a small section of the convento wall was all that was left by the 1950s. About

two-thirds of the mission site west of the Santa Cruz River at the base of “A”

Mountain was destroyed more than 30 years ago by a clay-mining plant and city

landfill. An 1874 photo showed only the outside of the two-story convento. Were the two cemeteries destroyed by the clay

mine and city landfill?

Gravestone at Laguna Cemetery,

Yuma County, Arizona.

My

write up on Laguna Cemetery on the APCRP website has photos of graves

that are probably Hispanic. In some early Hispanic or

Mexican cemeteries, from the late 1890s and later, tombstones often have

genealogy of the deceased engraved on them, so that the person's family names, etc, would be

preserved in the event that records were lost. An example of this practice is

shown above. This type of grave marker is seen in many Mexican or Hispanic

burials throughout the Southwest.

In

summary, Native American graves, particularly from prehistoric and historic

areas, have been excavated and studied mostly in the middle of the last

century. There is now a process to return artifacts and skeletal remains to

descendents or tribes of the persons buried in them. It is a crime under State

and Federal Law to disturb or desecrate Native American graves, as well as any

other graves one may find. Responsible people, such as APCRP members, often

photograph, research, and sometimes even restore grave sites for future

generations to ponder, as we all know. Certainly the small portion of the

public that vandalizes and desecrates Native American or other graves in search

of artifacts will continue to be prosecuted.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The information

in this article was obtained from:

Chatters,

James C. Ancient Encounters: Kennewick Man and the First Americans.

N.Y. Simon & Schuster, 2001. p.

268.

Cremony, John C. “Apache Burial

Customs,” Life Among the Apaches, as observed

by John c. Cremony, ca. 1862. History book on Internet.

Federal

Register,

Vol.73, No.45, Thursday, March 6, 2008. Notices. Internet.

Ferrell,

Clare. “Coming Home – the Returne of the Ancestors,” Native

Chicago, 1998. Internet article.

Hall,

Allan. Note with information about Snaketown and

other burial sites. October 5, 2009.

Hamilton,

Patrick. “The Early Spanish Missionaries,” The Resources

of Arizona, Prescott, 1881. Internet book.

Handbook

of American Indians North of Mexico.

Vol.1 and II, 1907, Smithsonian, Washington, D.C.

Reader's

Digest. “A

Day at Mission San Jose,” Story of the Great American West.

Reader's Digest, Pleasantville, N.Y. c.1977. 3rd

Printing, 1987. p.114.

Stauffer,

Thomas. “Rebuilding Convento is no Easy Task,” Arizona

Daily Star, May 24, 2002. Internet article.

Tumacacori National Historical Park. “Articles of

Historic Interest-Mission 2000.” 2005. Internet article.

Tumacacori National Historical Park. “Mortuary

Chapel and Cemetery.” Internet article.

Winter

Rabbit. “The Spirit of Goyathlay

(Geronimo).” Native American Netroots. Dec.20,

2008. Internet

article.

American Pioneer

& Cemetery Research

Project

Internet Publication

Version

101909-KB

WebMaster: Neal

Du Shane

Copyright © 2009

Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this

website may be used

for personal family history purposes, but not for financial profit or gain.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer & Cemetery

Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS