HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION

| GHOST TOWNS

| HEADSTONE

MINOTTO

| PICTURES

| ROADS

| JACK SWILLING

| TEN DAY TRAMPS

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Presentation

T H E H I S T O R Y

O F

C U L L I N G’ S W E L L

By

Carlos L. Hernandez

Copyright © 2000 by

Carlos L. Hernandez

All rights reserved

Reproduction by the Arizona Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project for the internet was authorized, sanctioned

and approved by Mary Hernandez, wife of the late Carlos L. Hernandez as well as

the approval of the Carlos Hernandez family.

A Special Thanks to

My Son

THOMAS A. HERNANDEZ

For His Help in

Researching the Drew and Culling Families

CONTENTS

Chapter Page

PROLOGUE

I

JOSEPH SAMUEL DREW 1

II CHARLES

C. CULLING 6

III

MARIA VALENZUELA 15

IV

LIFE AT CULLING’S WELL 20

V

A MOST DIFFICULT TIME 40

VI

BUSINESSMAN AND

PROSPECTOR 44

VII

JOSEPH DREW AND MARIA

CULLING 49

VIII

RETURN TO CULLING’S WELL 65

IX

THE LIGHTHOUSE IN THE

DESERT 112

X CONCLUSION 124

EPILOGUE

134

BIBLIOGRAPHY 135

Cover

Photo: Culling's Well from a

painting by Pauline With.

L I S T

0 F I L L U S T RAT ION S

Plate I, following Page 1

Plate I Joseph S. Drew

- Keeper of The

Lighthouse in the Desert.

Plates II through X, following Page

5

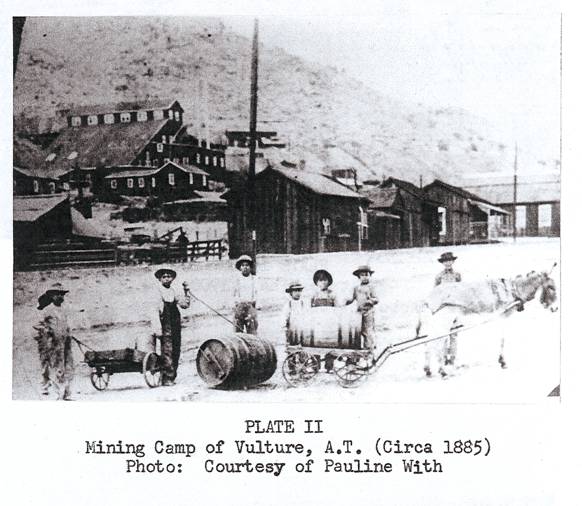

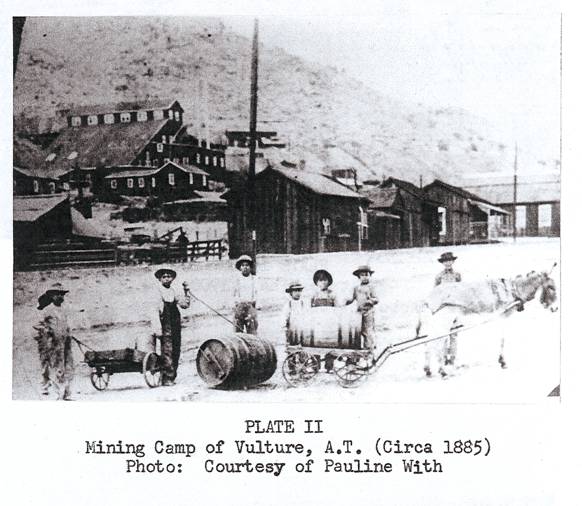

PLATE II

Mining Camp of Vulture, Arizona Territory (Circa 1885).

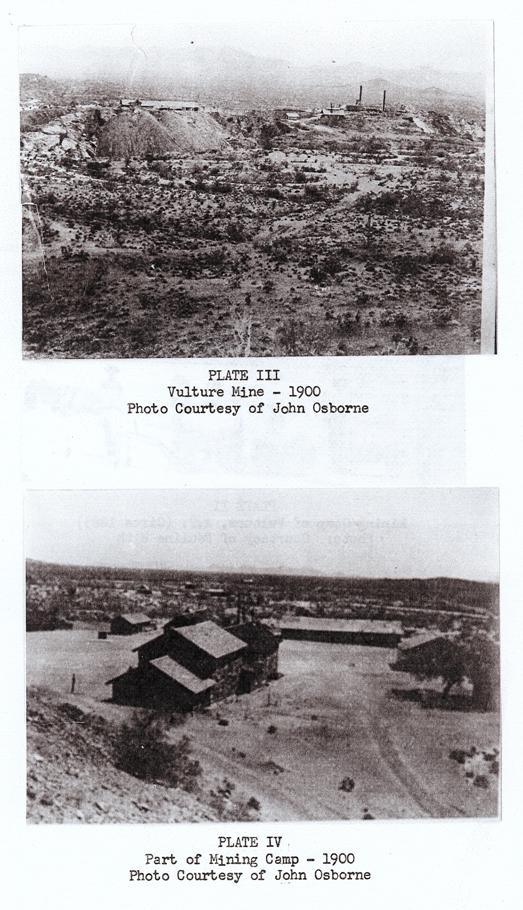

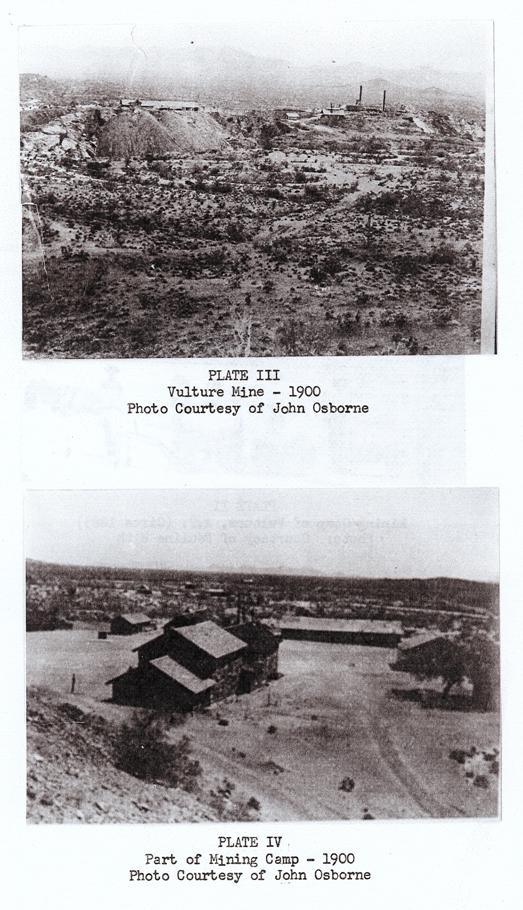

PLATE III Vulture Mine (1900).

PLATE IV

Part of Mining Camp (1900).

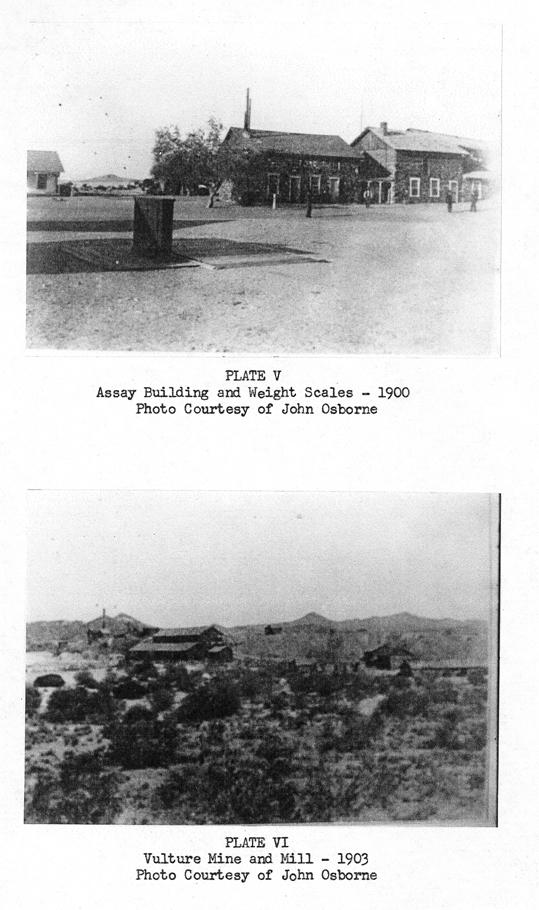

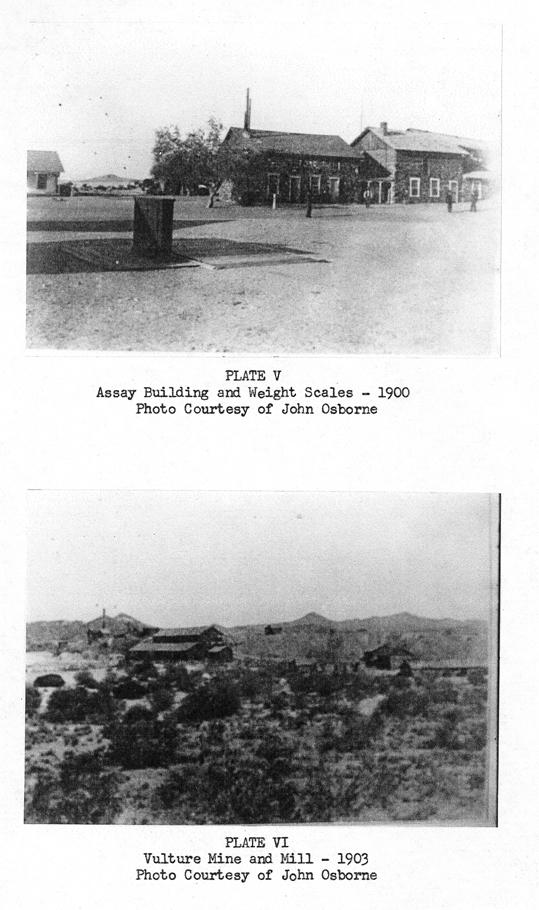

PLATE V

Assay Building

and Weight Scales (1900).

PLATE VI Vulture Mine and Mill (1903).

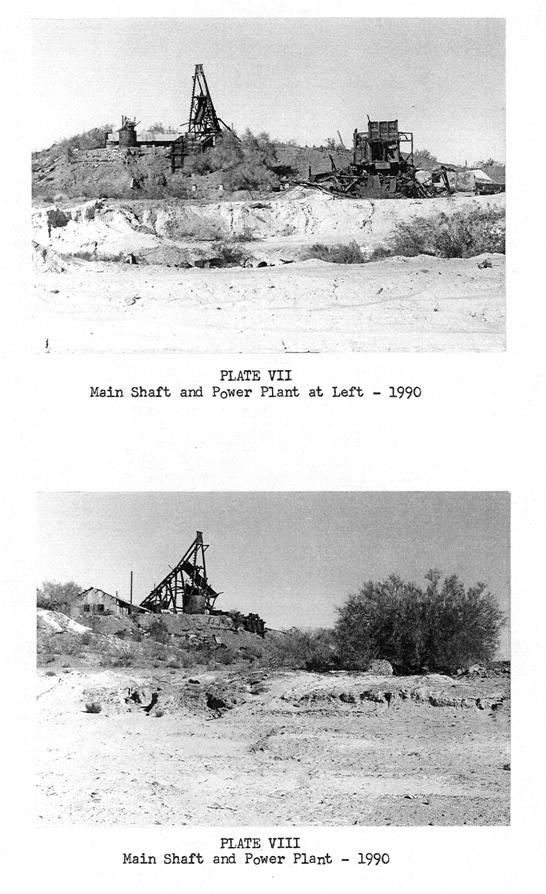

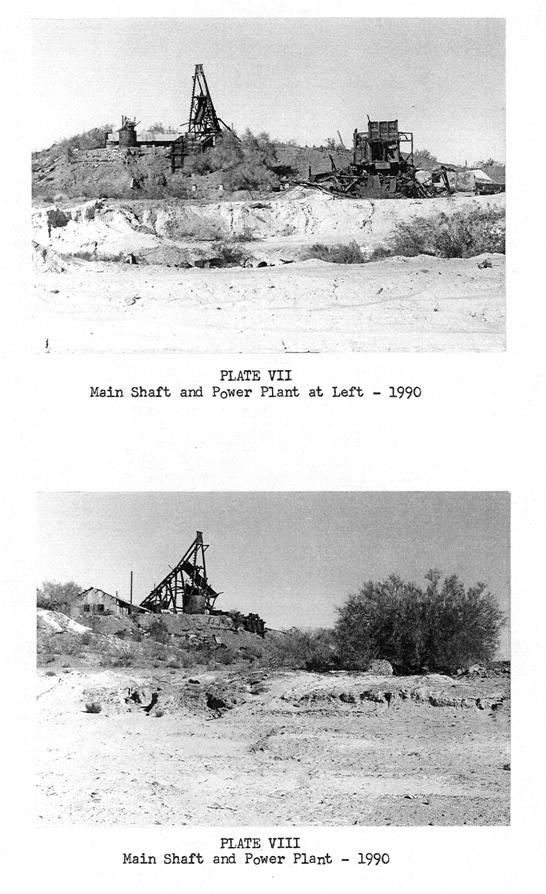

PLATE VII Main Shaft and Power Plant at Left

(1990).

PLATE VIII

Main Shaft and Power Plant (1990).

PLATE IX

Main Shaft (1990).

PLATE X

Ball Mill (1990).

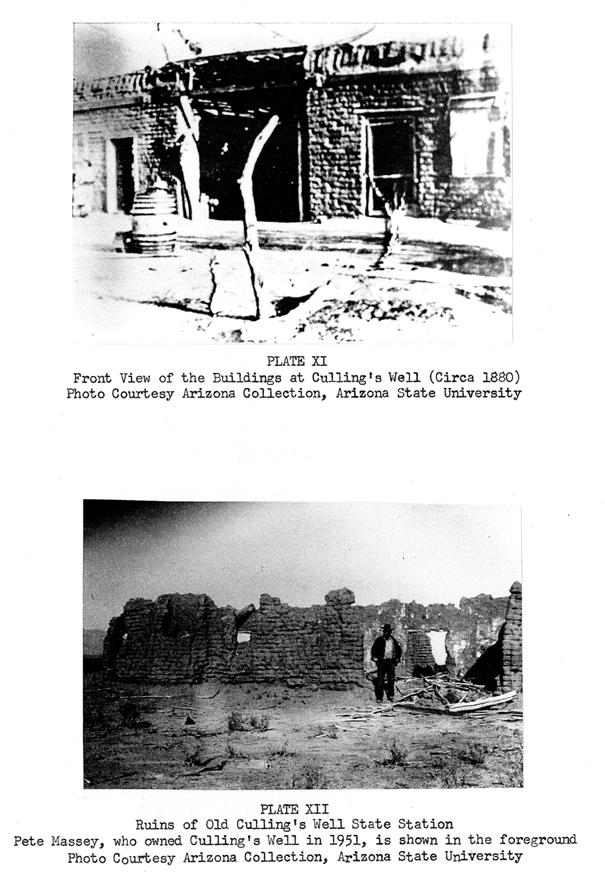

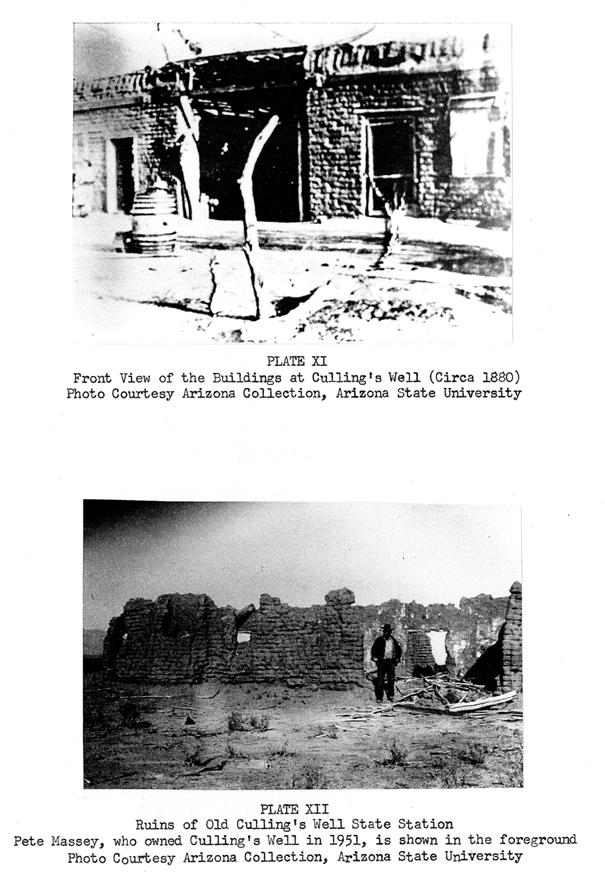

Plates XI through

XII, following Page 8

PLATE XI Front View of the Buildings at Culling's Well (Circa 1880).

PLATE XII Ruins

of Old Culling's Well Stage Station (Pete Messey, who owned Culling’s Well

in 1951, is shown in the foreground).

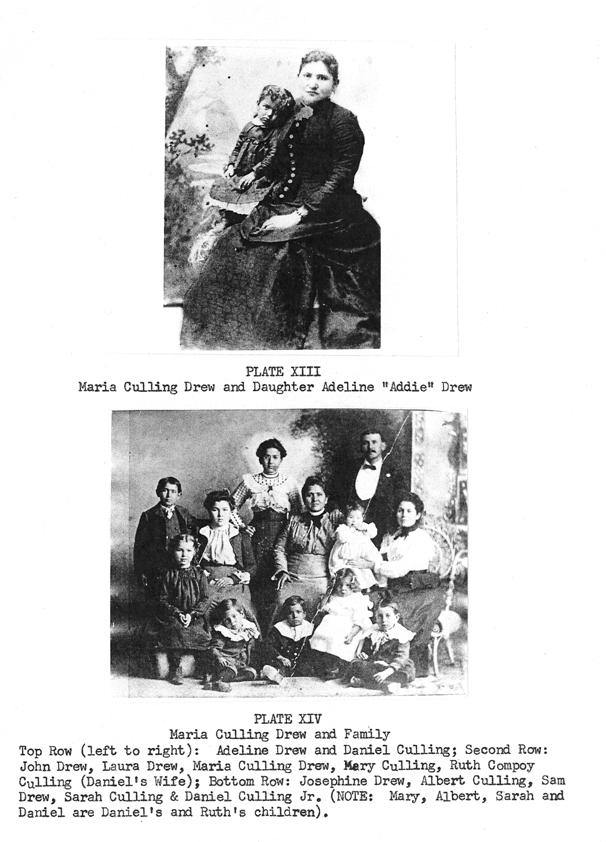

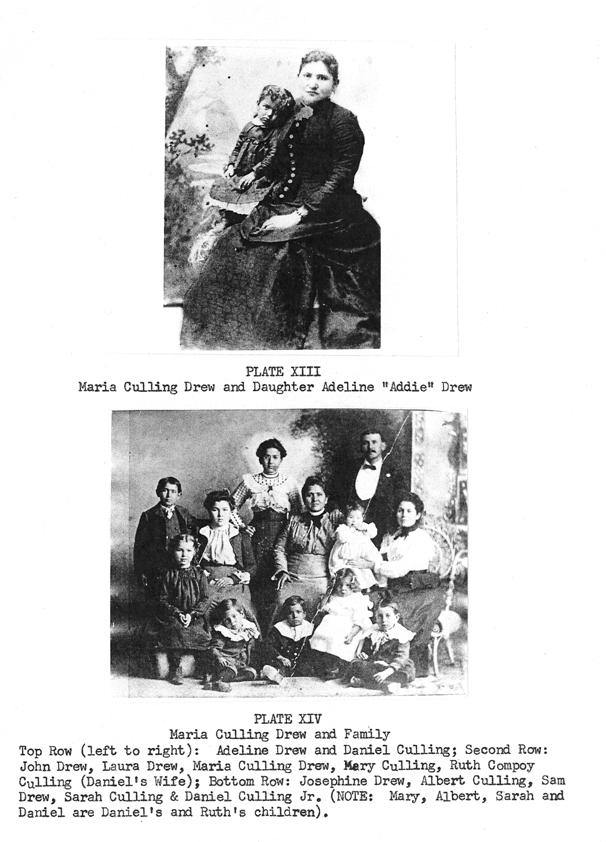

Plates XIII through XIV, following Page 19.

PLATE XIII Maria Valenzuela Culling Drew and

Daughter Melina “Addie” Drew.

PLATE XIV

Maria Culling Drew and Children.

PROLOGUE

Dozens of articles have been

written about Culling’s Well and of the Lighthouse in

the Desert.

Some of these articles have been

fairly accurate but some are too far-fetched and were not based on the true

story of this historic site.

I have based this publication on

facts as recorded by the daughter of Joseph S. Drew and Maria Culling Drew, Adelina “Addie” (Drew) Loza, and

on other historical documents.

My wife, Mary Laura (Drew)

Hernandez, is the granddaughter of Joseph S. Drew and Maria Valanzuela

Culling Drew.

Numerous members of the Drew and

Culling families still survive and this book is dedicated to these families.

Carlos L. Hernandez

August 13, 1990

THE HISTORY OF CULLING'S WELL

CHAPTER I

Joseph Samuel Drew

“He swung a lighted lantern from a

tall pole mounted on his well frame. The light was visible for many miles along

the trail, and for years it guided the weary travelers to water and safety.

Thus came into being the paradox of a lighthouse on a sea of sage and sand.”

This is the true story of Joseph S.

Drew, the founder and keeper of the Lighthouse in the Desert at Culling’s Well.

Joseph was born in Brooklyn, New

York, on September 14, 1845, to John S. Drew and

Sarah Pope. Both John and Sarah were born and married in London, England.

They came to the United States

in 1832 and resided in New York and various

places in the East until they moved to Burlingame,

Kansas on May 18, 1855.

The history of the Drew family is

chronicled in C.R. Green's “Early Days in Kansas,” Vol. II, and is well-documented.

John Drew was one of the oldest

"pioneers of Osage County,

Kansas. He was a well-known

figure there until his death in the city of Burlingame,

Kansas, on

October, 1897, at the age of 98 years and 6 months. Sarah Pope died at Burlingame on July 31,

1874.

John and Sarah’s family consisted

of George, Sarah, William Y., Josiah R., Elizabeth, Naomi, Charles P. and

Joseph S. (the youngest).

George and Sarah were born in England. Sarah

died there. The rest of the children were born in the United States.

PLATE I

Joseph S. Drew

Keeper of The Lighthouse in the Desert

- 2 -

George served as a Lieutenant in Co. I, 11th Kansas Cavalry and was wounded on December 7,

1862. After the Civil War he was appointed a clerk in the War Department at Washington, D.C.

and served in this position until his death.

William Y. also served as a

Lieutenant in the Civil War in 1861 in Co. D, 2nd Kansas Infantry. After the

War he served as county clerk until his retirement.

Josiah R. filled the Office of

Deputy Treasurer for many years and also served two terms as County Treasurer

in Lyndon, Kansas. He served in three organizations

during the War of the Rebellion, from 1861 to 1866: The 2nd Kansas Infantry,

as a Private; Co. I, 11th Kansas

Cavalry, as a Sergeant; and 2nd and 1st Lieutenant of the 18th U.S.

Colored Troops.

Elizabeth

was born in Boston.

She married Nathan Densmore who died on the first

anniversary of their marriage. Their only child, a daughter, was seven weeks

old when Nathan died, and she only lived to be six months old. This was a very

tragic life for Elizabeth, who remarried eight years later to W.P. Deming.

Naomi, John’s youngest daughter,

also met a tragic death at the age of seventeen. She drowned while on her way

to a Fourth of July celebration.

Charles P., fourth son in the John

S. Drew family, did service in Co. I, 11th

Kansas Cavalry, as· a Corporal, was wounded in the engagement at Prairie Grove,

December 7, 1862, and remained in service throughout the war. He later was

Captain of the militia company in Burlingame.

He was appointed Adjutant General in the Kansas State Militia, and, as of

October, 1915, was residing at Topeka,

Kansas.

Joseph, the youngest of John Drew’s

family, whose story is being written here, struck out for himself in early

life.

Approaching maturity at the close

of the Civil War in 1865, Joseph engaged

- 3 -

in mercantile pursuits in various Kansas towns, latterly at Fort Dodge,

whence he came to Arizona.

Joseph was a medical student in his

youth but the California Gold Rush, which lasted from 1849 to 1860, lured him

to the American \vest.

Joseph's first stop upon arriving

in Arizona was Prescott. He had the appointment of sutler (a follower of an Army camp who peddled provisions

to the soldiers) to the Sixth Cavalry while enroute

from Kansas.

By the time Joseph Drew arrived in Prescott, the city had

already been the site of the capital from 1864 to 1867. Almost immediately, Prescott had saloons,

stores, government offices and a $5,000 theater. The Ninth Legislature moved

the capital back to Prescott from Tucson in 1877. The

capital was moved to Phoenix

in 1889.

The return of the capital to Prescott contributed

substantially to the growth of the community.

Although Joe Drew’s first stop upon

arrival in the .Arizona Territory was at Prescott, he and a gentleman by the name of Ruggles decided to pool their resources, formed a

partnership, and decided that the place to make a fortune would be at Vulture,

where they did become very successful.

Vulture was fourteen miles

southwest of Wickenburg and was one of the largest communities in the Arizona Territory and nearly became its capital.

In 1863 Henry Wickenburg discovered

the Vulture Mine, one of the richest in Arizona’s

territorial history. There are various stories concerning how Wickenburg

stumbled across the mine. One is that he shot a vulture and on picking it up

noticed gold nuggets lying on the ground. The second says that his burro ran

away and in anger Wickenburg threw rocks at it until he noticed that one of the

rocks contained gold. Another reports that Henry

Wickenburg noticed a number of buzzards hovering over this peak at the time he

made his

- 4 -

discovery.

After the mine was in operation for

several years, a community grew at the millsite known

as Vulture City. There were forty-six dwellings and

nearly two hundred inhabitants in 1870.

After the cottonwood trees and

mesquite had been cut to feed the mill, it was moved down the Hassayampa to Seymour.

In 1879 the newly-formed Central Arizona Mining Company built twelve miles of

six-inch pipeline and erected an eighty-stamp mill at the mine. Soon Vulture City shifted from the Hassayampa to the new milling operation at the Vulture. The

town grew to support three hundred residents in the mid-1880's.

Although Vulture City

grew rich am lusty, it was reportedly an extremely dull camp. Stage robberies

provided some entertainment.

The Prescott Weekly Arizona Miner, dated

October 22, 1875 had this to say about Joseph Drew's initial venture at

Vulture: “Another store – C.W.N. Ruggles and Jos.

Drew have arrived here with a stock of general merchandise from Kansas, and

having leased a lot from A.L. Moeller are building a store house between Asher

and Co's new store, corner of Montezuma and Goodwin Streets, and Frederick and Heenan's tin shop. The building will be 24 x 50 feet and

front on Montezuma street, three doors north of

the Miner Office. Ruggles and Drew had the

appointment of sutlers to the Sixth Cavalry while enroute to Kansas

here and now propose to settle into a regular trade.” Joseph Drew was thirty

years old at the time.

These two entrepreneurs sold

everything from mules (Weekly; Arizona Miner, December 3, 1875), to groceries (Weekly

Arizona Miner, March 3, 1876), to Gentleman's hats (Weekly Arizona Miner,

April 14, 1876).

On May 19, 1876 Joseph decided that

being a storekeeper was not exciting, and prosperous enough for his tastes, so

he closed out his stock of groceries

- 5 -

and liquors to devote himself to

mining and prospecting (Weekly Arizona Miner,

May 19, 1876).

Joseph joined forces with R. Pittibone, Frank Shultz and Len Sivyer,

and together they went in search of riches and fame.

The Weekly Arizona Miner had

this to report on June 30, 1876: “Drew, Pettibone, Sivyer, Keys and Shultz and Co. have made another discovery

on Cherry Creek this time and are sinking on it. Len Sivyer

was in town day before yesterday and took out a bellows and other blacksmith's

tools, some grub, etc., and. say may have a good

prospect, but are not prepared to say how good just yet until they prospect a

little further.”

Joe Drew was well on his way to

becoming a successful miner and he had no way of knowing that what was

happening at Culling's Well, some thirty-eight miles west

of Wickenburg at the time, would change his life completely.

- 6 -

CHAPTER II

Charles C. Culling

Charles C. Culling was born in London, England

about IB25 and was a saloon keeper before leaving that country.

After the notoriety of California t s gold

fields swept 'round the world, adventurers of all kinds -- from every walk of

life, turned their faces west obsessed with one thought: sudden wealth. For

many of them, the long, arduous trek in California

ended in death; for others it meant only disappointment and disillusion. Many

had thrown caution to the wind -- had burned all bridges behind them. When

they found no gold, they were lost -- life held no purpose for them. Some tried

ranching. Some went to work on the clipper ships. And some moved into the

unexplored wilderness that was the Arizona

Territory. One such was

Charles C. Culling.

When Charles Culling arrived at

Arizona City (now Yuma) in 1864, and upon boarding a sturdy little steamboat,

piloted by Captain Isaac Polhamus, on the Colorado

River for La Paz, his mind took him back to his home in London; to the many

years he had spent at sea in that country, and he wondered if he would ever see

Great Britain again.

After a short stay at La Paz, he settled in Vulture City

and was one of the first employees of Henry Wickenburg at the famous Vulture

Mine. He then prospected the Weaver country in company with William H. (Bill) Kirkland, notable Arizona

pioneer.

Excerpts from the Special

Territorial Census of 1864, taken in Arizona, shows Charles C. Culling at 40

years of age, single, length of residence 9 months, occupation - miner. On

April 4, 1864 Culling signed a petition to have the capital located in the

Walker-Weaving Mining La Paz District. This, of course, never materialized. (Weekly Arizona Miner,

April 4, 1864).

PLATE IX

Main Shaft - 1990

PLATE X

Ball Mill - 1990

- 7 -

La Paz, located seven miles north of

present-day Ehrenberg, was a very rich and extensive gold-mining district. It had

its beginning when Captain Pauline Weaver, noted Arizona

frontiersman, discovered gold near the Colorado River

in 1862.

The first surge of people flooding

into the area had little to eat besides mesquite beans and fish, but it did not

matter. Gold was the answer to all problems. In the evenings miners and

gamblers would spread their blankets on the dusty street and play cards for the

heavy nuggets.

La Paz grew by leaps and bounds. A year later

the town, thronging with Mexicans, Indians and white men, numbered about

fifteen hundred citizens. It became an important landing and freighting point

on the Colorado River, and was the county seat of Yuma until 1871. La Paz

was previously considered as a possible capital for Arizona Territory.

Gradually the Colorado River

changed its course, leaving La Paz

abandoned as a steamboat landing. Placer gold began to give out, and people

scurried away to the more promising settlement of Ehrenberg down-river.

Charles Culling was a visionary and

he was aware that the California

and Arizona Stage Company ran two stages daily, one to the east and one to the

west, from Ehrenberg to Wickenburg and Prescott, and he also knew that this

same route was used extensively by freight teams.

It was at a site where the road

forked, the right hand branch going forty-five miles eastward to Wickenburg,

and the other more northerly via Camp Date Creek, forty-five miles, and thence

to Prescott, a

total of 105 miles.

In the latter part of 1865, Charles

Culling decided to establish a stagecoach station at the location where these

roads intersected, but before doing this he had to locate water in the

immediate vicinity.

Here, in this desolate location, in

what is known as McMullen

Valley, the

- 8 -

headwaters of the Centennial Wash, between the Harquahala Mountains to the south and the Harcuver Mountains to the north, Charles Culling set up a

tent and with the help of a Mexican by the name of Jesus Altamarino,

and other workers, they dug a well, some four miles from what was to become Culling's Well, to 200 feet, but they failed to find water.

Undaunted, and with a fierce determination, Charles refused to give up and then

moved to the Culling's Well site where at 240 feet

his tenacity paid off when a good flow of water, sweet and soft, was struck. He

continued down another 25 feet to insure a plentiful supply.

Thus was established Culling’s Well, an oasis in the middle of a lonely and

dangerous road frequented often by hostile Apache Indians eager to loot,

plunder and kill any unwary traveler.

Charles rounded up some men and

erected a large adobe building for protection against the Indians. In time he

was to add additional rooms to accommodate his family and occasional weary

travelers who stopped by for room and board.

The well furnished a fine and

unfailing supply of water. The water was cool and was drawn up from the

darksome depths of the well in a great bucket made from a wooden barrel. The

revolving drum above the mouth of the well was operated by a blindfolded mule

that knew - to an inch - just how many rounds were required to be made before

the dripping, clanking bucket would reach the top and

automatically empty itself into a trough. At other tanks and troughs - a short

distance from the station - always stood cattle and horses purchased by Culling

from time to time, and. which were turned loose on the range, but came there to

drink of the life-giving water.

In addition to the daily stage each

way (at first they had been weekly), many freight teams stopped at Culling's Well. Here animals were

watered at twenty-five cents per animal, or fifty cents per barrel. Culling was

shrewd enough to obtain a contract with the stagecoach line to have all their

stock

- 9 -

watered at the well. His business

soon became very profitable, to say the least.

The Butterfield Overland Mail

promoted adequate service across Arizona.

The stages that passed daily were six-horse affairs.

The movie-style Concord stage was used on the eastern and

western ends of Butterfield's run, but for crossing the deserts and mountains

the firm used a light-weight “Celerity Wagon” specially designed for the route.

It had upholstered seats which could be folded down to make beds.

Stagecoaches of that era had an

oval-shaped body resting on straps slung between the front and rear axles. This

type of suspension enabled the body of the coach to roll rather than jerk or

bounce when the wheels hit obstructions. Nine to twelve people could be seated

inside depending on the model and additional passengers rode on the top.

Mules, instead of horses, were used on the “Celerity Wagons”. These mules were

more adaptable to rough mountain and desert travel.

In her book, "Ghosts of Adobe

Walls, It Neil Murbarger writes: "It is not now

known, or will it ever be known, how many lives were lost in the course of

sixty odd years of staging in Arizona Territory. Indians, bandits, accidents,

heat and cold and thirst, each took its toll of the hard life of staging -- a

life that of times demanded the last ounce of courage from horses and mules,

drivers and swampers, station tenders, and

passengers.”

Charles purchased small amounts of

food at the Goldwater's store in La

Paz in 1867 and 1868. He also obtained stocks of food

for the station from the government, which he distributed to the Indians. He

hired a Chinese cook to prepare the food.

By now Culling's Well was becoming well-known.

The Weekly Arizona Miner

published this item on December 17, 1870: “Mr.

- 10 -

Calvin White of the firm of Allen & White, arrived home

on the night of the 13th from San Bernardino, California and had this to say

regarding Stations and Station-Keepers along the route: 'He is not very lavish

in his praise of a majority of the station-keepers along the route, and the

manner in which they keep their stations, but speaks in high terms of Charles

Culling, keeper of the station at Culling's Well,

who, he says, has a nice, clean place, and takes pleasure in treating travelers

well. Wish the others would copy after Charley. He know

it would be to their profit to do so.' “

The Arizona Miner of March 14, 1868 published a notice to all

teamsters and. travelers showing the "Safest and Best Route from the

Colorado River to the Interior of Arizona,” which included Culling's

Well, had this to say about the route: "Abundance of water for men and

animals at all times. There is plenty of feed on this route. The Indians are

peaceable on the route.”

Approximately a year later the

Indians were not as “peaceable,” for on February 26, 1869, the stage traveling

from La Paz to Wickenburg, carrying the mail and two passengers, and driven by

Bill Tingley, was attacked by Indians who had hidden

beside the road at Granite Wash (between the present towns of Hope and Salome).

As the stage approached, the Indians began shooting at the stage, which scared

the horses driving them right into another band of Indians concealed in the

high grass nearby. Driver Tingley, however, managed

to swing the team around and continued on towards Wickenburg while passengers

held the Indians at bay. During the fight both Tingley

and passengers were wounded but the horses finally outran the Indians and they

made it safely to Culling's Well.

The Apache Indian problem had its

beginning in the southwest in early 1861 when Lieutenant Colonel Pitcairn Marrison detached Second Lieutenant George N. Bascom and approximately sixty men to recover a white boy

and. some cattle that

- 11 -

had supposedly been stolen by the Chiricahuas earlier. Although Cochise, the Chiricahua chieftain, came into Bascom's

camp voluntarily, accompanied by several of his relatives and friends, Bascom had them surrounded and demanded the return of the

boy and the cattle declaring that Cochise and his party would be held hostages

until both were brought in. Cochise protested his innocence to no avail.

Sensing that the Lieutenant meant what he had said, Cochise drew his knife,

slit an opening in the side of the tent and escaped unharmed. One warrior

followed his chief through the hole in the tent but was killed. The other six,

mostly relatives of Cochise, were seized as hostages. This tragic and needless

episode became known as the “Bascom Affair.”

The "Bascom

Affair” so enraged Cochise that he launched a long and terrible war, intending

no less than the total extermination of all Americans in Arizona.

With the New Mexico Territory

stripped of troops due to the Civil War, the odds lay with the Chiricahuas. In two months they slashed their way through

dozens of white settlements in the Arizona

country and took 150 lives.

Most of the early governors

identified the hostile Apache as the chief obstacle to civilization in

frontier Arizona.

Governor Goodwin,

who had been appointed as governor to the Territory by Lincoln

on August 18, 1863 although the Territory

of Arizona was not

formally established until December 29, 1863 at Navajo Springs, requested.

that a sufficient number of federal troops be sent to

round up those Indians who persisted in plundering and desolating the

Territory.

In 1865, because of the Indian

depredations in the Territory, the district of Arizona, a part of the

Department of California, was placed under the command of Brigadier General

John S. Mason, who came east from California

with 2,800 men to re-garrison the old posts and to establish new ones. But

little was accomplished

-12-

by these troops as the Apaches

continued to raid at will, Then on April 15, 1870 the district was detached

from California

and made a separate department.

Under the command of Brigadier

General George Stoneman, a new policy was initiated

based on the theory that the Indians would respond to kindness, religious

instruction, and training in agrarian methods.

Stoneman

made treaties and established reservations with those Indians who would accept

them, and by feeding the Indians when they agreed to these terms.

The “Carnp

Grant Massacre” of April 30, 1871, in which a citizen army from Tucson,

composed of approximately fifty enraged Americans and almost one hundred Papago Indians, attacked a reservation for the Aravaipa Apaches near Camp Grant and killed one hundred and

eight of the Indians and carried off twenty-nine children into captivity, only

enraged the Apaches that much more.

Lieutenant Colonel George Crook

arrived in the Territory on June 4, 1871 and took command of the Department

from Stoneman. His job was to undertake a field

campaign to force the renegades to reservations. Cochise and the Chiricahua Apaches signed a treaty in which they were given

a reservation in southeastern Arizona.

He honored this treaty until his death on June 8, 1874.

After Cochise's

death, his oldest son, Taza, became the head of the Chiricahuas. Due to his lack of strong leadership the

tribe split with some of the tribe remaining in the reservation and the rest of

malcontents fleeing to the mountains determined to continue their open warfare

in 1876 under the leadership of a rising war leader, Geronimo.

Charles Culling, in the meantime,

continued to distribute government food, mostly flour and staples, and was

generally not bothered by the Apaches until January 18, 1871.

On January 23, 1871 a letter was

written to the Editor, Arizona Miner,

from Camp McDowell, Arizona Territory, which reads as follows: “I suppose are

- 13 -

this reaches you, you will have

heard of still another outrage at Culling's Well on

the La Paz

road. About daylight Wednesday morning, the 18th, the Indians ran nineteen head

of horses and mules belonging to Mr. Culling, and seven head of oxen from the

train of M. Cavaness. As soon as the loss was

discovered Messrs. Culling and Cavaness started in

pursuit, following them into the White Tanks. Finding the party was too large

for them to cope with, and the trail leading in the direction of the Verde,

they started at once for this post, and arrived here Saturday morning about 8

O'clock. As every available horse was out with Major Veil, after the stock of

W. B. Helling & Co., Colonel Sanford was

compelled to mount fifteen men part of them Infantry, on mules of the Q.M.

Dept. Lieutenant J. M. Ross was placed in command and started in immediate

pursuit taking a straight course to the Verde. About eight miles from the post,

the trail was struck crossing the river. Following it for nine miles they

suddenly came on the Indians, who were encamped, cooking and eating an ox. The

troops charged them, but the country being exceedingly rough and almost

impassable for horses, the Indians succeeded in getting off, though leaving in

their precipitate flight, every single thing they possessed. Nine horses, three

mules, and three oxen were recaptured, besides bows, arrows, knives, blankets,

etc.

As Lieutenant Rose’s animals were

completely used up and his party too small to enter far into the dangerous

country, he was compelled to return to the post, arriving here safely the same

night, with all the recaptured stock.”

(The article goes on to rake the

government over the coals for not mounting the Infantry, so they could be twice

as effective against the Apaches, etc.)”

Another raid by the Indians

occurred at Culling's Well

sometime in February 1871. During this raid a party of Indians shot one horse,

which they could not drive, and drove off another horse and six head of cattle.

The raiders were

- 14 -

pursued and the cattle recaptured.

In this vicinity the Indians had confined themselves to stealing corn, etc.

(Weekly Arizona Miner, February 11, 1871).

This was followed by yet another

raid, which was reported to the Weekly Arizona Miner on February 18, 1871 by

the driver of Grant's Stage.

On November 4, 1871 occurred what

became known as “The Wickenburg Massacre.” This happened when a stagecoach

bound for California,

with seven men and a woman aboard, was attacked on the Ehrenberg road, nine

miles west of Wickenburg. Six of the men, including a well-known scientist, and

a New York Tribune correspondent named Fred W. Loring,

were killed by Apaches. The two wounded survivors, William Kruger and a Miss

Nellie Sheppard probably were able to escape because the attackers began an

orgy on the “firewater” they found in the lucrative loot.

- 15 -

CHAPTER III

Maria Valenzuela

Things had quieted down at Culling's Well and construction was progressing on the

station when Charles Culling, now age 46, met Maria Valenzuela, who was to

become his wife and to share his life at Culling’s

Well for the years to come.

Maria Imperial Valenzuela was born

in Sonora, Mexico, on February 1857.

Her mother, Martina Imperial, had married Marcial Valenzuela in Mexico but Marcial

died when Maria was still a baby. Martina left Mexico

with Maria in tow and came to the United States when Maria was just

three years old. She came with her two brothers, who were cattlemen, and

settled in the lush region of what is now Imperial

Valley, California.

The Valley was named after the Imperial family.

Martina was described by her

granddaughter, Adelina (Drew) Loza, as “small, independent, and industrious and

refused to depend on her relatives for substenance.”

There was very little work to be

had by women in those days, so Martina decided to go to the gold rush camp of La Paz to try to set up a

boarding house. She was an excellent cook and the miners were in sore need of

good food.

As mentioned previously, gold was

discovered in La Paz

in 1862 and was a boom town of 1,500 inhabitants when Martina and her child,

Maria, made the trip there.

Building materials in the mining

camps were almost nonexistent. Most individuals lived in tents, so Martina put

up one large tent with suitable tables in the center, which would serve as a

dinning place, and to one side she set up a small kitchen. Another tent she

kept for herself and Maria. When she opened for business, she was literally

swamped with customers. There were just too many and she could not possibly

cook for them all. Nevertheless, she took in as many

- 16 -

as she was able to and in this way,

even though the work was hard, she made a good living and felt happy and

secure.

Things went well for Martina. She

became quite independent by having her own little business, and a good income.

Indeed, she never lacked customers in all the years she maintained her boarding

house. Whenever possible, she would purchase a cow, thus supplying the miners

with fresh milk and cream for their steaming hot cups of coffee. Her day

started around 4 a.m. with a cold bath summer or winter. In a large trunk she

kept her clothes and undergarments folded neatly and carefully. Dressing

quickly, with her hair parted in the middle, and drawn tightly in a bun, she

would head for her kitchen and another day of hard work.

Martina prepared three meals a day

for the miners: Hot biscuits, delicious roasts, and a favorite that was enjoyed

by all -- baked ribs with almond chili. This latter dish permeated the whole

area with a mouth-watering aroma. If the miners wished to take a lunch with

them, she would prepare one tortilla rolled up with a filling of

chili-eon-carne, another with refried beans, and another with chopped green

chili, onions and tomatoes, seasoned with garlic, salt and pepper. These would

stay hot and fresh until they were consumed and represented a hearty and

well-balanced meal to the hard-working gold miner. This menu certainly beat

the steady diet of mesquite beans and fish that these workers had been used to

prior to Martina's arrival at La Paz.

It was here at La Paz in late 1865 that a gentleman by the

name of Charles C. Culling made his appearance at Martina's boarding house. He

introduced himself as an Indian Agent authorized by the government to set up a

station and briefly described the proposed side between Wickenburg and

Ehrenberg. He asked if Martina would board him for a few days until the well

was dug at the station. She agreed as Mr. Culling appeared to be a very kind

individual. The well completed,

- 17 -

Charles returned to Culling's Well

to oversee the management of the station. Maria was now eight years old.

The boom lasted about two years at La Paz and after the Colorado River changed its course,

and La Paz was

abandoned as a steamboat landing, Martina pulled up stakes and, like most of

the inhabitants, moved to Ehrenberg. Here she lived, busy and content, doing

what she loved most -- cooking. It was now 1869 and Maria was twelve years old.

It was here also at Ehrenberg that

Martina, after years of austere living and tedious hours spent at her work,

that she decided to remarry, for she wanted security and companionship for

herself and Maria. Unfortunately, her marriage to Jesus Osuna

turned out to be more of a tragedy than a blessing for Jesus was a miserable,

abusive wretch who demanded to be catered to and expected both Martina and

Maria to wait on him hand and foot. To him both Martina and Maria were nothing

but servants and treated them as such.

He took Martina’s hard-earned money

to spend on liquor, and who knows what else, for he never did any work. Most of the time he stayed drunk and had a violent temper.

Maria, for nights at a time, would lay shivering in fright as Jesus inflicted abuse upon her

mother, not knowing when he would burst into her room shouting and raving at her

also. Maria lived in constant fear of him and when she would see him coming,

especially if he was intoxicated, she would run over to a neighbor's house to

get out of sight.

Things got so bad at home, putting

up with her abusive stepfather, that Maria even

thought of leaving home, although the thought of leaving her mother was almost

unbearable.

Charles Culling never lost touch

with Martina and as the years went by, and with the station making daily

progress, he returned to Ehrenberg in 187l

- 18 -

but by now, fully aware of the

miserable life Maria, now age 14, had been experiencing, he decided to discuss

Marla's situation with Martina.

Jesus Osuna,

Maria’s stepfather, had absolutely no respect for Charles or Charles' presence

there so it was obvious to Charles that Maria was under a terrible strain and

it pained him deeply to see her thus.

Charles was not unattractive, was

46 years old, and he had endeared himself to Martina and to Maria by his

kindness and thoughtfulness during the time he had boarded with them. Charles

told Martina that he had been seriously thinking of Maria and that perhaps he

could offer this young girl a happier life than the one she was facing now.

Martina told Charles, with tears in her eyes, of all their suffering am unhappiness,

and said that she had just about decided to send Maria away to live with some

relatives. Charles then asked Martina's permission to marry Maria and he went

on to assure her that he would make a good home for her and to take care of her

always. Martina hesitated because of Maria’s age, who was still playing with

dolls, but she knew deep in her heart that Charles meant all he had said and

she also knew that Maria would only suffer more there with her stepfather. In

the end she told Charles that she would talk this matter over with Maria, being

careful not to press her, but letting her make the final critical decision.

In the meantime Charles returned to

the station to await Maria’s decision. The more Maria thought of marriage to

Charles, the more it seemed to her a blessing, an answer to all of her

problems. She was not in love with him but admired and respected him very much

and this was akin to love. She even felt a gladness in

her aching young heart at getting away from her abusive stepfather, she came to

a decision.

When Charles returned, rather

apprehensively, to Ehrenberg in December of 1871, Maria told him the news he

had been so anxious to hear. Yes, she would

- 19 -

marry him and this pleased and made

Charles very happy.

Charles Culling and Maria

Valenzuela were married with Martina's blessing. This item appeared in the Weekly Arizona Miner, December

23, 1871: “Married at Wickenburg, December 17, 1871, by W.K. Ferris, J.P., Mr.

Charles Culling and Miss Maria Valenzuela, both of Yavapai County. The ceremony was celebrated with

wine, chickens and other good things."

Later, because Maria was Catholic, they were married by a

priest.

- 20 -

CHAPTER IV

Life at Culling's Well

You have heard of men who fought and

died for gold and silver. You know of those pioneers who struggled to raise

cattle on the frontier. You have seen a motley assortment of men and women --

all seeking, fighting, dreaming.

There was a man who found what he

sought not in a vein of gold or a herd of cattle but in a stream of crystal

clear water. This man was Charles Culling.

Yes, Charles had found two

treasures: The crystal clear water in McMullen Valley's

Centennial Wash and he had found. Maria Valenzuela -- now his bride.

At first the desert was very lonely

and quiet and Maria was the only girl at the station. Also, she was young and

full of fears, especially of the Indians, who attacked isolated settlements

like theirs without warning. Charles reassured her by telling her that the Indians

had already heard of these stations which supplied them with food and for this

reason he doubted they would be harmed. As it turned out, Charles was quite

right. Food was very precious to the Indian and he would not do anything to

jeopardize this gift of the white men, although he regarded the intent with

deep suspicion. That the Indians were close by, however, was apparent in the

loss of stock in 1871.

Charles tried hard to win Maria's

confidence and, since he was a wise and kind person, he realized that she was

young, not yet over the trials of the past few years, and not ready for .the

responsibilities of marriage. He knew also that she missed her mother very much

and promised her to take her to Ehrenberg to see her mother soon. In the

meantime he bought her a gentle pony and a new saddle. Maria was delighted with

her pony and spent much time exploring this wide and lonely countryside. There

was not much for her to do at the station since Charles already had a cook and other workers to do the chores.

- 21 -

Maria was a good rider and enjoyed

this newly found freedom immensely. Charles cautioned her not to wander too

close to the mountains since they were occupied by large bands of renegade

Apaches.

A few of the Indians had already

ventured down to the station and Charles had distributed some food. This action

seemed to please the Indians for they were always hard-pressed for food. They

eked out a bare supply of food from the desert and had very little meat.

The station had been constructed in

1868. Using what Indian and Mexican labor he could muster. The large dwelling

finally erected resembled a fort.

It consisted, at first, of four

rooms with a wide hall running down the center. The stage station walls were of

unusual thickness, consisting of adobe bricks made at the site. Pine poles were

placed across the roof, and a layer of brush was piled on next. After that came

a heavy layer of dirt, well-packed down. It is said that this roof never

leaked. The walls were all whitewashed with lime. Later some storage rooms were

added to the central building. Adjacent to it was a small corral enclosed with

an adobe wall about five feet high, with only one gate entrance.

Charles had stocked a large supply

of food and goods, such as roadside stores handled in those days, and he also

stacked a goodly amount of liquor. The station also served as a mail drop.

The Indians were coming down from

their dwellings in larger numbers, as Charles had anticipated, but never making

a hostile move. Usually they would linger at a distance to watch the station's

activities.

Maria, riding side-saddle on her

pony, had become a familiar sight to the Indians and they never harmed her in

any way as she took her daily rides through the desert. The fact that they did

not harm her will seem quite remarkable to anyone when you consider that these

same Indians were ambushing the stages and killing the settlers.

-22-

The Apaches were a handsome people - standing straight and

tall and with regular, bold features. The women, as a mark of beauty, had their

chins tatooed in straight lines, running from the

lower lip to the bottom of the chin. The women of the tribe did most of the

work in addition to some basket-weaving and pottery-making.

The Indians began to come every day

to the station for food and they were extremely curious about the station and

everything in it. They gathered in the doorways or stood at the windows looking

at the furniture, the wood stove, and especially at Maria as she went about her

duties. Occasionally Charles would show them how to prepare some of the food

and they seemed willing to learn.

David S. Chamberlain (1848-1933)

was a relatively well-known Arizonan. He lived in Tombstone for a short time and while there,

developed some of that city's first wells. Later he became a millionaire in the

manufacture of patent medicine. In his early years he did a great deal of

prospecting in the Arizona

Territory. His views of Culling's Well in 1871 appeared in

the Arizona Republican, dated

April 20, 1932, and titled “Journey to Arizona

in 1871.”

"Our last stop was Cullen's

(sic) Wells, which was also a stage station. The regular stages ran weekly, but

another weekly mail was carried between times by a buckboard, without carrying

passengers. We arrived at Cullen's (sic) Wells early in the morning. Cullen

(sic) had a small corral, enclosed with an adobe wall about five feet high,

with only one gate entrance. We got our animals inside the corral, and

proceeded to get breakfast. I remember buying half a dozen eggs from Charles Cullen

(sic). A lot of Indians from the Date Creek Agency were there. I fancy there

must have been at least 150. They wanted to get into the corral and were

begging for something to eat. I ordered them to vamos

but they seemed very persistent so I took my six-shooter and told them to

'pronto

- 23 -

vamos.’

My partner was very much alarmed, thinking that I was starting a fight and that

we would both be killed but we got them out and kept them out. It was very hot

and dusty and we had little rest, as only one of us slept at a time, the other

sitting with a Henry rifle over his knee. Frequently, some of the Indians would

peak over the wall but none of them entered in.”

David Chamberlain and his partner,

for the matter, were rather lucky in their dealings with these Indians. Later

that same year was when the “Wickenburg Massacre” took place less than

forty-five miles from Culling's

Well.

The stage station grew during the

following months. Freight wagons brought new doors and windows and some

furniture from San Francisco.

New additions were made to the already existing structures, and Culling

increased his herds of cattle and horses, and added flocks of chickens.

However, all was not fun and

profit. Another Indian raid took place in 1872.

This item appeared in the Weekly Arizona Miiner

on March 9, 1872: “F. Hawthorn, who came up this week from Culling's

station, informs us that he, himself, lost four mules; S.O. Miller, of this

place, two mules; and William Yerkes, one horse. And coming back next day, the

same party of thieves took a horse out of the herd while Ed Lamley

was doing his best to drive them away. Hawthorne, Charles Culling and some

Apache-Yuma Indians followed the trail of the thieves but did not catch up with

them."

Another disaster befell Charles and

14aria on July 1872.

This time a band of Apache Indians

raided the station and stole some more stock. Maria did not witness this

attack. During 1872 a series of raids on the station netted the Indians 132

head of stock; they partly destroyed one corral; burned 200 tons of native hay.

On several occasions, Charles and

his hired hands would give chase but, except

- 24 -

on one occasion when Charles and

the cowboys retook the stolen stock, the Indians usually got away leaving not a

single trace.

This was not all because on

September 14, 1872 the “Weekly Arizona

Miner” published this article: "On the night of September 4,

Apache-Mohave Indians stole eighteen head of animals from. Culling’s

station, and five more from a. station further on the

road, towards Ehrenberg.

This we learn from a note from A.O.

Noyes, who, with his family, had got that far on his way to California.”

It was around this time that one

sunny day the stagecoach arrived as usual at the station. By now Maria had

become quite bored with life at the station and she decided she would learn to

cook. She had been very annoyed for some time with the Chinese cook, who

considered the kitchen his personal domain and resented Maria’s presence there.

He let it be known that the kitchen was off-limits to everyone, including the

boss's wife, and would definitely not tolerate anyone fussing around and

getting in his way. This didn't deter the stubborn Maria,

for she was determined she would learn to cook regardless of the consequences.

The way she went about this was to peek in through the open door when the

Chinese cook had his back turned and watch him prepare the meals. In this way,

she at least learned the basics of cooking and made up her mind that as soon as

she became proficient she would give this arrogant cook his “walking papers.”

The stagecoach stopped and Maria,

who by now felt that she was capable of preparing the meals, prepared the hot

meals for the passengers while the drivers watered the horses at the well.

On this particular day, a friend of

Charles alit from the stagecoach much to Charles' surprise and joy. His name

was Christian Berry.

Christian Berry, a native of Charleston, South

Carolina, had enlisted as a Private in Company H, 7th

Regiment California Volunteer Infantry on November 6, 1864

- 25 -

and mustered on December 9. He saw

service in California and Forts Yuma

and Mason, Arizona Territory before being discharged at

Drum Barracks on March 1, 1866.

“Berry,” as he was called by everyone, worked

at the Vulture Mine, Wickenburg, after his discharge. The 1870 Census taken on

August 20, 1870 shows him at Vulture at the time. Although it is not certain if

Charles knew him from there or not.

By occupation, this five-foot,

seven-inch, fair-complected and blue-eyed and blonde

Southerner was a miner.

Upon arrival at Culling's

Well, Christian Berry’s intention was to visit with Charles for a while before

continuing on his way to look for a job.

Somehow Charles persuaded him to

remain at the station as an employee.

During the evening meal he had

noticed the short temper of the Chinese cook, which was rather obvious. He told

Charles that he had been a cook in the Army and offered to take over the

kitchen duties as part of his job there. Charles and Maria were delighted and told

him that the job was his. The excellent, but sullen Chinese cook quit in a fit

of temper, which saved Maria the trouble of firing him.

Berry turned out to be clean and efficient

and an excellent cook. He taught Maria the finer points of meal preparation.

His favorite meal was barbecue. He would dig a pit in the ground, surround the

interior of the pit with pre-heated rocks, then he

would place a couple of large choice cuts of beef in the pit. The pit was then

covered and the beef allowed to cook the entire night.

In the morning the beef was extracted and it was so tender that it could be

sliced with a fork. He also prepared corned beef and taught Maria how to make

butter and cheese since milk was plentiful. There were always large rounds of

cheese and butter on the table and large pitchers of molasses to pour over Berry's golden, flaky

biscuits.

- 26 -

Berry also helped with the heavy chores

around the station and with the stock. In fact, Berry had found his place in life at Culling's Well and became the

major domo, or jack-of-all-trades, of the establishment.

On October 12, 1872 Charles Culling

was appointed Precinct Inspector for Precinct Deep Wash at Culling's

Well for the general elections scheduled for November.

What this job entailed is not known but obviously Mr. Culling was well known in

the Territory by this time.

Although Culling Station was rather

isolated from other white establishments, there were always travelers passing

through to keep Maria from becoming too bored or lonely.

On one occasion, she even invited a

friend of hers, Mary, from Wickenburg to come and visit with her at the

station.

Winter passed quickly and in early

spring, Mary finally arrived at Culling's Well to the delight of Maria.

This was a particularly beautiful

time of the year in this desert country. The early morning air was always cool

and refreshing and the world seemed permeated with the faint scents of mesquite

and creosote blossoms. The washes would be carpeted with wild flowers creating

a riot of color from marigolds, poppies, lilies and blue lupine. The sounds of

birds were everywhere, as if welcoming the joy of spring, and it was into these

surroundings that Maria and Mary rode their ponies almost daily.

One particular day as these two

tomboys were riding fairly close to the mountains, which were extremely

dangerous due to the Indians lurking nearby, they happened upon a large nest in

a Palo Verde tree. The tree being rather shady was an open invitation for them

to sit under its green branches to rest from their ride. As they sat under this

tree, both kept wondering what kind of bird would build such a large nest.

- 27 -

Perhaps an eagle had built it but Maria had never seen an

eagle in this area. Curiosity got the best of Maria and scrambling up the tree

she peered into this nest only to be confronted by a rather large lizard which

hissed at her. The lizard, nearly two-feet in length with a stout body and

covered with black, orange and yellow scales, resembling beads, was a Gila

Monster -- a venomous lizard that is capable of inflicting sometimes fatal

wounds. This startled the brave Maria, who jumped down from the Palo Verde with

the Gila Monster following close behind. What this

creature was doing up the tree is uncertain but Maria learned a very important

lesson, beware of the desert. Maria and Mary needed no urging to sprint for

their ponies and gallop back to the station.

Upon arrival at the station they

could see a number of Indians gathered as usual around the doors and windows,

talking and gesturing amongst themselves and pointing at different things,

which were all foreign to them. They had never seen a wood stove nor dishes or

other furniture. They had no idea how the white man prepared his food, how this

food tasted, or even what they ate. In time, Charles would hand out to the

Indians different dishes that had been prepared as they could sample them. The

rest would gather around eagerly to watch. First the sample dish was smelled

then cautiously eaten. It always amused Charles to watch this ritual and to see

the surprised, almost comical, expressions that came over their faces. They

seemed to relish every dish, so Charles gradually began to give them a little

more variety of food and often showed them how to prepare it.

Maria began to venture out on her

daily rides with more confidence. The Indians seemed friendlier somehow,

perhaps it was the way Charles treated them. At any rate there was little

hostility in their attitude toward Maria and Charles as compared to what it had

been earlier. Charles felt that perhaps they had finally reached some sort of

understanding with the Apaches.

- 28 -

One day an old squaw, who gave her

name as “Chacha,” appeared at the ranch and told

Charles that if he would go with her to a certain mountain, she would show him

where a large gold mine was. She indicated this in sign language as she spoke

only a few words of English. Charles was quite familiar with the Apache sign

language and was able to communicate with her. Charles was rather skeptical

about the squaw’s information and he feared that perhaps this woman was trying

to lead him into a trap. After all, some of the renegade Apaches were still on

the warpath although those visiting the station seemed friendly enough. While

these thoughts were running through Charles’ mind, the old squaw stood by

quietly waiting for a sign from Charles. In the end Charles decided to go with

her but asked one of the cowboys working at the station to accompany them. When

the squaw understood what Charles wanted to do, she shook her head decisively

and indicated that either Charles went alone with her or the deal was off and

she firmly refused to budge. The lure of gold was too strong to resist so

Charles agreed to go with her but, as an added precaution, he slipped a six-shooter

into his pack before they departed.

The range of mountains where "Chacha” told Charles where the gold was to be found was

some seven miles from the station and were known as the Harquahalas.

Harquahala

means “running water” or Ah-ha-qua-hale – “water there is, high up” to the

Mohave Indians. An earlier name for the mountain was Penhatchapet

(1865), probably because on their south slope was a spring called Pen-Hatehai-Pet water. By 1869 this same spring was being

called Hocquahala Springs and the name was gradually

used to include the mountains themselves. The attempts of white men to wrap

their tongues around this word has resulted in various spellings, among them Huacahella Mountains and Har-que-halle Mountains. They are, name and all, the

most massive in Central-Western Arizona.

- 29 -

"Chacha”

led Charles towards these mysterious mountains until they arrived at a sort of

divide and then she stopped close to a spring of cool water. She dismounted and

sat down on a large flat rock. Charles, thinking that she was tired and

thirsty, started to sit down also in the shade of a mesquite tree. She would

have none of this and insisted that Charles keep on looking for the gold. She

was very superstitious about revealing locations of gold or treasures of any

kind to a white man. She believed that if she did show him the exact location

of the gold, she would be denied entrance into the "happy hunting grounds”

in the hereafter. On the other hand, if this white man found the gold by

himself, she would not be guilty of this offense.

Charles, by this time, was in a

frenzy of excitement thinking that he was within sight of this fabulous gold

mine, so putting aside tiredness and heat, he wandered around the area, poking

here and. there, lifting rocks and digging into sand and dirt with his pick

until exhausting himself completely.

Finding nothing, and with the

evening shadows creeping up gradually, he decided to spend the night near the

spring and return to the search the following morning.

Early the next morning, just as the

first rays of the sun made their appearance, Charles began the search again,

almost frantically, but to no avail. All day he toiled with the “gold fever”

deeply burning into his already tired body. This effort produced absolutely no

trace of any gold or gold ore and, in anger, decided to end this useless search

for the legendary treasure. Picking up his gear, he disgustedly took one more

look at these taunting mountains and started back to the station as the

deepening shadows blanketed the Harquahalas

concealing their earthly treasures, perhaps forever.

The squaw, a smile upon her rugged

features, shrugged, mounted her horse and followed silently.

- 30 -

Ironically, in 1869, just three years

before Charles Culling went searching for the allusive gold mine, it was

reported that a Pima Indian had made a big strike in the Harqhahila

(sic) Mountains but the San Francisco

Chronicle asserted many years later that an Army officer first struck gold

there, only to be driven off by Apaches. The same newspaper stated that five

prospectors had managed to slip into the area while the Apaches were on the

rampage a take $36,000 in surface gold before clearing out several days later.

In fact, as early as the 1860's,

reports had filtered out that gold had been discovered in the Harquahalas by three Frenchmen who had come to Yuma and had deposited

eight thousand dollars in gold at George Hooper's mercantile establishment.

Although attempts were made to follow these miners back to the source of the

gold mine, neither the Frenchmen nor the mine were found. It was assumed that

the Apaches had killed the Frenchmen before they revealed the location of the

bonanza.

Charles, of course, had no way of

knowing this at the time.

The Lost Squaw Mine was discovered

in Spanish times. The conquerors of Mexico

found the mine in the Adonde (now Copper Mountains)

Range near Baker's Tank, and took out several million dollars in gold. For some

reason known only to them, they abandoned the mine after some years.

There are several contradictory

versions regarding the Lost Squaw Mine.

Indians knew where the mine was

located but kept it a secret. One generation after another described its

location to their young men, with the admonition that to disclose its site to

an outsider meant death. Squaws were never told the location of the mine

because they talk too much. One young Indian woman did learn about the mine in

spite of the effort to keep the information from females.

Another version places the Lost

Squaw Mine in an area somewhere south of

- 31 -

Cullen's (sic) Well. The Prescott Courier was the original

source of this tale.

According to the Courier, “back in 1872, when

General George Crook was chastising the warring Apaches, a sick squaw appealed

to Charles Cullens (sic) to allow her to remain the area rather than be removed

to a reservation. Cullens (sic) granted her request.

While talking to the old squaw, Cullens (sic) noticed that she had ear rings of gold. He

asked where she got them and she replied that the gold came from a mine far to

the west in the desert. When Charles asked if she would take him to the mine,

she agreed to take him part of the way because of his kindness. After the woman

took him some distance and gave him directions, Cullens

(sic) went on alone. Before he was able to find the mine his water ran out and

he had to give up the search. Cullens (sic) died

without having found the mine.”

The legend of the Lost Squaw Mine

was to pop up again in the late 1880’s and early 1890's.

The year was 1873. Maria was now

sixteen and a half years old and was expecting her first child. Since the

station was so isolated, it was decided that Maria would stay with her mother,

Martina, at Ehrenberg while the baby was delivered, and for a short time after,

or until she felt well enough to return to Culling's

Well.

Charles left the ranch in Berry's very capable

hands and he and Maria set out for Ehrenberg. Daniel L. Culling was born on

August 18, 1873. Charles was overjoyed over his birth. He hastened back to the

station to make preparation for the new baby. He ordered a crib, garments, and

other essentials that Maria would need for the newborn and he and Berry anxiously awaited

their return.

Maria was soon back

on her feet, feeling strong and healthy. Her mother's excellent care and

equally good food put a bloom in Maria's face, and the baby was doing well. In due time she came home to the station and took up her house-hold

duties.

- 32 -

Now that she had an infant to care for, the time flew by

with busy days for them all. Berry

loved the baby too and aided with his care and welfare whenever Maria needed

him.

One day, not long after her return

from Ehrenberg, Maria was working in the kitchen when a squaw silently entered

unannounced. By now Maria was familiar with these Indians and had even picked

up some of the Apache language. The squaw had a little boy with her. He

appeared to be about nine years of age and seemed quite shy. She approached

Maria and taking the youngster’s hand gave him to Maria telling her that the

boy was being offered to her to have as her son. This was rather unexpected and

Maria was, to say the least, astonished beyond disbelief. She stood there,

practically in shock, looking from the squaw to the lad and could not believe

what was transpiring. Her first impulse was to refuse,

for she had her hands full with her own Daniel and the work to be done at the

station was tedious enough without having to worry about a nine-year old child.

Maria was hesitant and did not respond immediately but the squaw kept insisting

that she take the Indian boy as her own. Maria's heart melted as she gazed at

the little boy, who was obviously frightened. The squaw was looking hard at her

with narrowed eyes. Perhaps this would be an insult of the worse kind to

refuse, she thought. Perhaps it would prove dangerous to the people at the

station. She nodded her head in agreement and the squaw left abruptly without even a thanks for Maria's compassion. The Indian boy was

left sitting there looking very forlorn and lost.

Under Maria's tender care and love,

the boy responded and gradually overcame his shyness. The household named him

“Apache John.”

“Apache John” was obedient and

quick to learn. After he had been at the station several months he arose in the

middle of one night and ran across the desert, and back to his home in the

mountains, without losing his way in the darkness.

- 33 -

Maria and Charles were worried since “Apache John” was no where

to be found and they couldn't imagine what had become of him. Charles and some

of his men searched high and low for the boy without success. Soon a small band

of Apaches came to the station and explained to Charles that “Apache John” had

returned to the tribe. This, Maria thought to herself, is the end of

"Apache John’s” stay with them. However, a few days later the same squaw

appeared again at the station with “Apache John" in tow insisting that

Maria keep him there. Apparently “Apache John" was the son of an Apache

chief but he seemed relieved to be back with Charles and Maria.. This same episode was repeated several times over as it

was obvious that “Apache John” had mixed emotions regarding the Cullings and his own tribe. After Maria accepted the young

boy's peculiar behavior and all went well.

The Apaches were at it again when

they pulled another raid on Culling's Well in 1874. This time they got away with twenty milk cows

and one bull. It was suspected that during these raids, Yuma, Mohave and Hualapie

Apaches were involved. This was based on eyewitnesses.

That same year, while Charles was

camped at Black Tanks, about twenty-five miles northwest of the station, the

Apaches stole three horses and thirteen of his mules.

In May, 1875, when Daniel was only

two years old, Mrs. Martha Summerhayes, one of Arizona's earliest and

most interesting historians, stopped off at Culling’s

Well. She was the young wife of Second Lieutenant John

Wyers Summerhayes, of the

8th U.S. Infantry, who was on duty in the Territory from 1874 to 1878.

Mrs. Summerhayes

was on her way from Fort Whipple, Prescott, to

Ehrenberg on the Colorado

when she reported: “The third day brought us to Cullen’s (sic)

- 34 -

Ranch, at the edge of the desert.

Mrs. Cullen (sic) was a Mexican woman and had a little boy named Daniel; she

cooked us a delicious supper of steamed chicken, fried eggs, and good bread,

and then she put our boy to bed in Daniel's crib. I felt so grateful to her;

with a return of physical comfort. I began to think that life, after all, might

be worth the living.”

1876 was a year filled with joy and

tragedy for Charles and Maria.

Their joy was the birth of their

second son, Charles, who made his grand entry into this world on March 1876.

Again, the birth of another son filled Charles with extreme happiness.

Two months after the birth of

Charles disaster struck. The Weekly

Arizona Miner of May 5, 1876 summed up the entire tragedy in just

seventeen words: “Cullen's (sic) station below Wickenburg was almost entirely

destroyed by fire, including clothing and household effect.”

Culling launched into an immediate

rebuilding program; a year passed before the station was restored to its

previous condition. In his work the Englishman was greatly aided by Christian

Berry.

The Arizona Sentinel had this to report in its March 10, 1877

edition: “Charlie Cullen's (sic) new house at Cullen’s (sic) Wells is rising

like a Phoenix from the ashes of his old one and he is in a fair way to make

good the losses he sustained by fire."

Apparently Charles was in a hurry

to complete the station because in the same paper, the following item appeared:

IMMIGRATION -- Captain Mellon tells us that he was told at Ehrenberg that at

least 150 families were on the road between Indian Wells and Ehrenberg on their

way into Arizona.

Plenty room for more.

The Wickenburg road is fairly lined

with travelers on foot, horseback and in vehicles of every description drawn

from one to sixteen animals. Station keepers are doing well and getting rich.

We might be doing the same if “Griff” would do

- 35 -

more and talk less about the road

from here to the railroad terminus.”

Not that Charles was becoming rich,

but he was doing quite well financially. Not long after the birth of “Charlie,”

as he was called, the stage came to the station as usual one particular day and

to everyone’s surprise out stepped Maria’s mother, Maria was very excited and

happy to see her as it had been a while since she had seen her mother. Martina

was on her way to the Vulture, Mine, which was now one of the biggest mining

camps in the Territory, and she, Martina, intended to open a boardinghouse

there. Her purpose of being here at the station was to spend a few days with

her daughter, her son-in-law, and her young grandchildren. Martina had four

other children now with Ramona, about six years old, being the eldest. So

mother and daughter talked and laughed and had a pleasant visit during the

short time Martina was there.

One afternoon they witnessed a very strange phenomena, something very few people have

ever witnessed.

It was one of those clear and

bright afternoons, so typical of the desert. Maria and Martina were seated in

the hallway, which acted as a breezeway. Even on hot days, this breezeway was

cool and pleasant. The children were taking their afternoon nap, their siesta,

when suddenly Maria and Martina heard a low-roaring noise. They both scrambled

outside to determine what was creating this peculiar noise. Coming directly

toward the station, from the southeast, they saw, to their astonishment and

horror, what appeared to be a huge ball of fire. It was quite low and moving

extremely fast. This object had a long tail of smoke and passed directly

overhead, so close that the children awoke crying and frightened out of their

wits. They stood there, side by side, in shock, as the mysterious heavenly

object disappeared over the mountains. This meteor was also witnessed by Berry and some of the

ranch hands. This experience not only left Maria and Martina awed and

frightened but they wandered what this omen meant for all of them.

- 36 -

Things returned to normal again at

the station after Martina departed for Vulture Mine. Maria and Berry were doing all the

cooking for the hired help and the stage passengers. Besides, now Maria had

three more mouths to feed: Daniel, Charles and “Apache John.”

Christian Berry had become so

attached to the station that he often told Maria that he would never live

anywhere else. Maria and Charles could not have gotten along without him as he did

most everything around the station. Once, in the course of a conversation with Berry, the subject of

why he had never married arose. He explained that he had experienced a great

disappointment when as a youth he had fallen in love with a beautiful girl and

even became engaged. All their plans had been made, the wedding date set, and

she had already purchased her wedding gown. Such was not to be, for the day

before the wedding was to take place, this lovely girl died suddenly.

Disappointed, Christian Berry made a vow never to marry. He had found his place

here at Culling's Well and here he would remain, with

Charles' permission, until the day he died.

With his business in good hands,

Charles took frequent business/pleasure trips to Ehrenberg, Wickenburg and

Prescott. The Prescott Arizona Miner

often wrote of Charles Culling respectfully. On August 12, 1877 this item

graced. page 3, column 3, of this newspaper: “Charles

Culling of Culling's Station on Ehrenberg road, known

to nearly every man, woman and child in this section, is in town. A more

accommodating man does not exist.”

And the April 26, 1878 edition of

the Weekly Arizona Miner

praised Mr. Culling for saving two children from death: “BUIlD

A FOOT BRIDGE -- Yesterday, as Mr. Chas. Culling

happened to be passing Granite Creek, he espied two small

- 37 -

children rolling down the stream,

crying for help. They were passing the creek on a plank that served as a

temporary bridge when they lost their balance, or became frightened, and fell

in. The current, which is quite swift, carried them away, and had it not been

for the timely aid given by Mr. Culling, the smaller of the two would certainly

have been drowned.”

This was followed by an item in the

Arizona Enterprise of April

27, 1878: “Charley Culling of Culling’s Well, on the road to Ehrenberg, is in town looking younger

than when we first knew him. He says the road is now well stocked with freight

teams, all bound for Prescott.”

The following month, on May 3,

1878, the Weekly Arizona Miner

further praised the station keeper: “Chas. Culling, a kind hearted gentleman

and owner of a good station on the Ehrenberg

Road, has been doing our town for the past few

days; however, having completed the business which brought him here, he took

his departure yesterday for his home. Mr. C. has probably given food and

shelter to more destitute persons during the last ten years, then any other man

in the Territory.”

Daniel, age 5, Charles, age 2, and

“Apache John” had become good companions. Maria was making plans to improve the

living quarters of the station in order for all of them to live a more

comfortable life. Not only that but with another child on the way, she was in a

hurry to get things going.

Just when it seemed that things

were finally going well for the family, Charles suddenly, and unexpectedly,

came down with a very high fever and it was evident that he was, in fact, very

seriously ill. No one at the station knew what to do for him, or even imagined

what was the cause of the illness. Maria and Christian

decided to take him to Wickenburg to see a doctor, but before anything could be

accomplished, Charles became progressively worse. Help was summoned via the

next stage but before help arrived Charles was dead and Maria was

- 38 -

stunned by the sudden turn of

events and. her grief was obvious. Charles was fifty-four years of age when he

died on August 4, 1878.

There was not a newspaper in all

the Territory of Arizona at that time which did not carry

an obituary eulogizing him.

The Arizona Enterprise of August 7, 1878 offered this obituary:

“A brief note from Mr. C. Berry, dated August 4th, informs us of the death, on

that day, of Charles Culling at his station, on the Ehrenberg road. Mr. Culling

was long and favorably known to travelers and residents in the Territory. He

was an old settler here and has lived at the place that bears his name, for

several years. He was a native of England, and. was about 50 years old. Was a good, whole souled, jovial man, and. his hearty welcome and pleasant

countenance will be missed by his old friends along the route. No notice of the

burial was received.”

This was followed by the following

in the Weekly Arizona Miner of

August 9, 1878: “We have received the sad news of the death of Chas. Culling,

the friend of all. Mr. Cullling was stricken with

paralysis on the 2nd last, and on the 4th just 48 hours after his spirit had

left the body, and passed to that sphere of which but little is known. Mr.

Culling was one of Arizona's

oldest and best citizens. He settled where he died, about 12 years ago, and has

ever since continued to reside at Culling’s Station,

where the weary were welcomed and found rest, the hungry whether accompanied by

plenty of the needful or otherwise, food. There is not a person who ever knew

Charley Culling but what will mourn his loss. He was Englishman by birth, and

at the time of his death, about 54 years of age.”

Finally, the Arizona Sentinel published this brief obituary on August 10,

1878: "Charles Cullen (sic) died a few days ago, at his station, of

paralysis.“

Upon Charles Culling's

death, some soldiers came to the station immediately

- 39 -

and buried him right there at Culling's Well, a short distance from his beloved station.

His grave was surrounded with a small, white picket fence and a large wooden

cross to mark his final resting place.

Charles C. Culling’s

desire to see his sons grow to manhood; his wish to once again return to

England, the country of his birth; his dream of perhaps sailing on the high

seas; his desire to locate the legendary Old Squaw gold mine, were never

fulfilled, but he left a legacy which was hard to duplicate in the years to

come.

- 40 -

CHAPTER V

A Most Difficult Time

Marla was devastated after the

death of Charles. She realized she could not manage the station without Charles

around and so she made preparations to take her children and temporarily move

to Yuma where

some of her relatives resided and until she could sort things out. “Apache

John” was sent back to his own tribe in the mountains. Since he had practically

become a member of the Culling's family, his

departure was a tearful one. Charles had not left any funds to speak of,

although the station and stock were rightfully hers.