HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet Presentation

Version 032809

By: Allan Hall

Dry Stack Walls - A Pioneer Legacy

Part One:

The construction of dry stack walls (that is, wall

construction without the use of mortar), has been a feature of human

development for thousands of years.

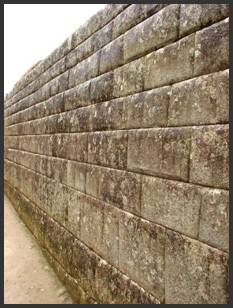

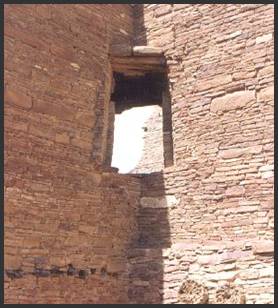

Extraordinary examples of dry stack stonework can be seen at Chaco

Canyon in New Mexico; cliff dwellings in Arizona and Colorado; Mayan

architecture in Mexico and Central America; and at the Inca city of Machu

Picchu in Peru - to name only a few.

These examples show that prehistoric cultures recognized the importance

of durable construction and, at least in the case of

Figure 1a,

The history of dry stack walls in our neck of the desert may not be as ancient, durable or glamorous as the sites mentioned, but the region still provides a rich testament to this type of construction dating to the latter half of the nineteenth century. These examples owe their use to mining, pioneer settlement and the development of transportation in Territorial Arizona. Their construction was for utilitarian purposes and achieved their desired results while maintaining a conscious focus on economy.

The purpose of this article is to describe, through photo and text, a historical context for the type of dry stack construction you are likely to encounter in the mountainous mining areas. As fellow historical researchers of the pioneer days, locating and identifying these structures will increase your “situational awareness” of routes to mines and settlements. I must caution you that the vast majority of dry stack walls that I have found are not located along or near a modern road. This means that careful observation, the use of field glasses, and some moderate degree of hiking may be required to locate most sites. Although the variations of dry stack construction are almost limitless, this discussion is confined to five topics:

1. A brief history of events that led to the development of mines and pioneer settlements and, consequently, dry stack walls

2. Stage coach and freight roads – walls that supported major roadways in mountainous grades

3. Mine trail construction – shoring up light duty horse/mule trails to prevent washout from rain

4. Terrace foundations – stacked walls constructed for mine operations, housing and cemeteries

5. Miner’s cabins – crude living structures (permanent or temporary) to provide a protected dwelling place

Note: These five topics will be

provided in four separate articles, beginning

with a “brief history” and a discussion

of dry stack walls used for “stage coach and freight roads” in Part One. Subsequent articles (topics 3-5) will be

posted as free-standing material in the coming weeks.

The quality and the durability of wall construction varied greatly during the pioneer and prospecting era.. Once you begin studying these structures it becomes relatively easy to distinguish the “Do it yourself” method from well-engineered and patiently constructed walls. For example, an itinerant mine worker might only have been interested in blocking wind and rain with a temporary shelter, where a mine owner needed a durable road that would not wash out during seasonally heavy rainstorms. A dry stack terrace wall at a mine had to be well-engineered to support tons of shipping ore and the constant vibrations of a stamp mill, while the construction of a foundation wall for a house or cabin did not require the same standards. It probably came down to the individual’s sense of permanency and the resources at their disposal. For a “jack” who may have earned $3.00 per day in the tunnels and shafts of a hard rock mine, there was no incentive to make an investment in a permanent structure.

Similarly, primitive pack trails that crossed the rugged mountainsides might be only two feet wide and did not require the scale or precision of wall construction demanded by wider roads that were needed to support heavy loads of equipment and ore shipments.

So, with this introduction, let’s examine a bit of history

and then study a few of the dry stacks that you will find in the vicinity of

the Wickenburg/Weaver/Bradshaw mountain ranges (east and north) and the

A (Very) Brief History

Stage coach and freight companies depended upon reliable

roads and trails to transport passengers, dry goods, mining supplies and even

hay from the major transit points along the Colorado River to the interior of

the

In fact, roads were so scarce and poor in the early 1870’s that

milling equipment could not be transported to major lode mines in the interior

of

The U.S. Commissioner of Mining Statistics, Mr. Rossiter W. Raymond, lamented this fact in his 1877 report to Congress.2 He begins with an acknowledgement that hostile actions between the Apaches and settlers had ceased (if only temporarily):

“After many years of tedious and costly conflict, the Apaches and other

hostile Indians occupying this Territory have been forced upon reservations,

and so long as Congress furnishes the money for supplying them with food, they

will not interfere with mining operations, which heretofore they have at many

points impeded and at others absolutely prohibited.”

But he also appealed to Congress for the need to establish “cheap and quick” transportation that would enable a more rapid development of mining in the Territory:

“But the peaceful condition of the country [Arizona], with all its

attendant advantages, and the value of many of the mines, (which is no longer a

question of doubt,) are not sufficient to overcome the need of cheap and quick

transportation, which next to the Indian troubles, has ever been the serious drawback

to the rapid settlement and profitable development of this remote

Territory. The past year has witnessed

an increased attention to mining and the investment of some new capital, but

the distances, both from the Pacific and Atlantic States, are such, and many of

the roads to the mineral districts are so heavy or rough, that no expeditious

and economical movement of ores, machinery, or miners, no working or shipment

of low-grade ores, and no influx of capital (even from California) can be

looked for, and consequently no extensive or very important operations can be

carried on until at least a trunk railroad crosses the Territory.”

If you were a miner with several tons of mill ready ore (but no mill), or if you needed equipment and supplies, then you would understand why good roads and trails were vital. The railroad did not reach Wickenburg until 1877. Even then, transportation between a railroad town and the remote mining sites and settlements depended upon horses and mules. That helps explain why arrastres (the poor man’s mill) were heavily used in the remote mining areas and - more than likely - explains the absence of milling operations even at many large mine sites. Milling equipment was simply too bulky or heavy to transport over these “rough and heavy” roads.

One of the most interesting statements made in the annual

report by Mr. Raymond is a complaint about the difficulty of obtaining reliable

statistics regarding ore production in

“For some reason or other the miners of Arizona have always been slow

to avail themselves of opportunities to make their discoveries and developments

known through Government reports, and to this day it is about as difficult to

estimate the annual yield of gold and silver in the Territory as it was when

the first mining operations were begun, there being as yet no official record

kept of the shipments of dust, ore, or bullion either to California or to the

East.”

The honorable commissioner did not seem to appreciate how dangerous it could be for a miner to advertise how much ore he was shipping! Even in 1875 there were no express offices to handle the shipment of gold or silver ore, so there was no means of recording its value. Outbound mail wagons carried gold bullion by the pound because postage (per pound) was 96 cents and was considered to be cheaper and safer than other means of shipment. John Wasson, the Surveyor-General of Arizona, stated that miners were “…constantly carrying out bags of gold and gold bricks and some silver bricks, all taking the utmost care, for prudential reasons, to conceal from the public both the fact and amount thereof.”

It is apparent that the absence of “cheap and quick” transportation was a limiting factor in the development of the mining industry and pioneer settlement in the Territory. To this I would add the prolonged and persistent issue of safety. From the early 1860’s until the mid-1870’s, prospecting expeditions might be comprised of 30 to 300 men armed with rifles. The threat of attack by Apaches and other hostile groups, including bandits, was real and endured for many years.

Wherever you were headed in the

Nevertheless, an important chain of events unfolded over the course of several decades that led to the success of mining and pioneer settlement. Those events are tied to the discovery of potential ore veins and the subsequent development of economical transportation, summarized as follows:

o Major deposits of gold, silver and copper are found in the early 1860’s followed by

o A rapid influx of prospectors

o No

economical means of transporting ore for processing are available, so mine

development languishes in the interior of

o Railroad arrives in 1877

o Mine owners build roads between railheads and their mines

o Mining activity and production capacity expands

o Settlements and commerce expand, generating an influx of mine workers and settlers

To be certain, there was mining activity in the

Thousands of Chinese laborers were let go when construction of the transcontinental railroads was completed in 1877. Stated a bit more bluntly, these laborers were essentially abandoned by the railroad companies and left to their own means for survival. Many of the laborers in the Intermountain West found work building roads and trails into the mining districts.3

Chinese were not the only source of labor for building roads

in the vicinity of Wickenburg. Charles B.

Genung, a founder of

Stage Coach and Freight Roads

When you are exploring remote areas you will be presented with many opportunities to spot historical features, such as the dry stack wall shown below. Notice that the actual “road” is virtually impossible to detect because trees and shrubs now cover the route.

Figure 2,

The dry stack wall shown in Figure 2 is part of a stage coach road east of Wickenburg, situated between Hamlin Wash and Morgan Butte, south of Buckhorn Road. This road runs in an easterly direction for several miles and then branches in three directions (north, east and south). It connects to several historically important mine sites and settlements. The view in this photo looks in a westerly direction. This road probably pre-dates modern Constellation and Buckhorn Roads by two or three decades. Unless you are particularly observant, you are unlikely to see this feature, since there is only one viewpoint that exposes the old road.

I have selected this particular photo to illustrate several points:

o The original surface and slope of an old road or trail will inevitably be altered by decades of runoff and sedimentation that settles onto the abandoned roadway.

o Natural growth of vegetation will eventually reclaim the original margins of the roadway.

o A dry stack wall – regardless of its size – may be the only way to locate an old road.

Figure 3,

The view in Figure 3 is a closer examination of the dry stack wall shown in Figure 2. This photo angle is only possible by hiking from above (right) to this south-facing slope, or via foot, horse or ATV from below (left). It is a particularly impressive dry stack wall; measuring nearly 100 feet in length and approximately twenty feet high at the center.

The builders of this wall are unknown to me but, based upon legend, were probably Chinese laborers. A notable feature of the wall is that it had a “staggered” construction. In other words, the upper portion of the wall was offset from the lower portion. This allowed the upper wall segment to rest upon the reinforced foundation below it and contributes to overall structural integrity. Close examination of the wall reveals that many of the rocks were shaped to provide a tight fit. Also, the individual rocks do not protrude from the contour - the exposed surface of the wall is generally smooth.

Within a few hundred yards of this location there are another half-dozen dry stacks. Where there are no walls to support the roadway, sedimentation from the uphill slopes has virtually erased any evidence of the road and native vegetation has obscured what remains of the original roadway. These dry stack walls have survived the elements for nearly 140 years and remain in wonderful condition to this day.

If you think of mine roads as branches from a stage coach route (that is, “highways” leading to arterial roads and trails), then you can find many trails that will take you to old mines. Figure 4 shows a dry stack wall that was part of the famous “$17,000 Road” constructed by George Mahoney between the settlement of Constellation and O’Brien’s Gulch. One of the dry stacks is visible to the left and right of the Saguaro cactus in the photo center. Mahoney discovered the Gold Bar Mine in 1877, but was constrained from transporting supplies and heavy equipment by the lack of an adequate road. He undertook the construction of this road in 1884 to address the problem.5

Figure 4, Mahoney's Road

To the left and right of the Saguaro cactus you can see a dry stack wall that is considerably more modest in construction than what is shown in Figure 3. In contrast to the previous wall, this dry stack made use of more “irregular” shaped rocks. In other words, the rocks were not shaped by stone masons to provide a tight geometrical fit. Instead, the placement of individual rocks in the wall was based upon their individual shape. Mahoney’s road was narrower and less well engineered, but it served its purpose very well. I have never attempted to count the number of dry stacks on the route between Constellation and the bottom of O’Brien Gulch but I estimate there are at least a dozen walls along this route. The road is now nearly 130 years old. Today it can only be traveled by foot for the entire length, but the walls remain a testament to its durability.

Other stage coach and freight road walls have not survived the test of time, as seen in Figure 5. In this example, the ravages of weather have claimed the center portion of the wall. In spite of its collapse from seasonal flooding, it still serves as a marker to pioneer activity. And that is an important point! What you should be seeking is evidence of pioneer activity. Its condition doesn’t really matter. What is important is that you are able recognize dry stack walls so that you can identify (or trace) a route that might lead to a pioneer settlement or mine.

Figure 5, Collapsed Dry Stack Wall

What do these photos suggest to you? To me, I see careful, well engineered construction in Figures 2, 3 and 5. The rocks were carefully stacked and, when necessary, were shaped by stone masons to provide the best possible fit in the wall. Even though the dry stack in Figure 5 has partially collapsed, it is only the result of heavy runoff on a road that has been abandoned for at least a century. Figure 4 suggests, to me, a more economical approach to construction. It did not require shaped stonework but it is still well constructed. The hillside roads shown in Figures 2, 3and 5 were also generally wider than Mahoney’s Road into O’Brien Gulch.

It is important to consider that these roads were not “public” highways in the sense that we are accustomed today. They were all constructed at the expense of a mine owner or stage/freight company for the purpose of expediting the transport of supplies, equipment and passengers. They were, in effect, only as wide and sturdy as needed to accommodate the type of traffic of the era and to endure (without excessive maintenance) for as long as possible.

The next article (Part Two) will deal with mine trail construction and will illustrate a different type of trail structure and dry stack walls. Examination of these trails and walls will show that they were typically more economical and designed with more modest objectives than what you have seen in Part One. In the meantime, if you have any questions or suggestions, please let me know.

Notes and References

1. Weaver, Date Creek, Vulture, Wickenburg, Buckhorn, McAllister, Silver, Hieroglyphic and Bradshaw mountains north and east; the Harquahala mountains to the west, to name only a few.

2.

“Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and

Territories West of the Rocky Mountains, Being the Eighth annual Report of

Rossiter W. Raymond, U.S. Commissioner of Mining Statistics”, pp 341-354.

3.

The 1870 Federal Census of Yavapai County lists only

thirteen male residents of Chinese origin.

Their occupations are described as laborers, laundry men or cooks. There were probably more uncounted Chinese

workers in the mining districts at the time.

Completion of the railroads through the

4.

“Massacre at Wickenburg”, page 89. R. Michael Wilson. The Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 978-0-7627-4453-4. Genung was employed by the

5. I have conflicting historical references regarding the founding date of the Gold Bar Mine. Some references indicate 1877, while another states 1888. Other references state that George Mahoney constructed his road from Constellation to O’Brien Gulch in 1884.

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet Presentation

Version 032809

Webmaster: Neal Du Shane

Copyright © 2009 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this website may be

used

for personal family history purposes, but not for financial profit of

any kind.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer &

Cemetery Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS