HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet Presentation

Version 050109

Dry Stack Walls

– A Pioneer Legacy

By Allan Hall

The third article on Dry

Stack Walls provided photos and interpretive text on the identification and

construction of walls that can be found at mines and settlements; including

heavy walls for mining operations, corrals, retaining walls and foundations. Part Four describes walls built for the

purpose of constructing terraces.

Part Four: Terrace

Walls

Previous

articles have focused on dry stack walls that were primarily built for

transportation, mining activity and corrals.

We now turn to walls that served a much more personal need – the

construction of terraces for housing and for cemeteries. The fundamental purpose of a terrace is

to provide a flat area in terrain that is not naturally level. I submit that there are no naturally

occurring flat areas in the mountainous mining districts of

Figure 1, Terrace Wall for Buildings

The criteria I

use to classify a terrace are based on two simple, but essential, points: First, there must be an upper retaining

wall (whether natural or man-made).

Second, a lower wall must also be present.

The area between these upper and lower structures is (or was at some past time)

essentially “manufactured” flat ground. Figure

1 provides a clear example of a terrace.

In this case, the upper wall was cut into the rocky hillside and the

lower dry stack wall was constructed using shaped stone. It should be evident that the terrace

area was created by providing additional fill soil.

This terrace provided space for two houses, as evidenced by the remains

of the wood structures in the center of the photo.

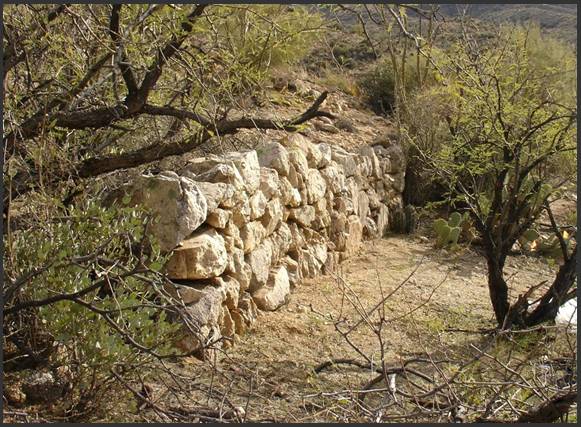

Figure 2, Typical Dry Stack Terrace

Walls,

Figure 2 is possibly the best illustration I have found of a terrace wall

structure that provided a “nearly perfect” flat area.

The combined height of both walls is nearly five feet (from the bottom of

the lower wall to the top of the upper wall). Sedimentation at this site has been

effectively eliminated for more than one hundred years, even though the two

walls were constructed using irregular (unshaped) native stones. As in Figure 1, fill soil was used to

create the flat terrace.

In case you haven’t already noticed, the two walls in Figure 2 and the lower

wall in Figure 1 rise a few inches above the level of the soil. Why is this?

Take another look at the uphill side of the terrace in Figure 1, where

two things become obvious: (1) Steep

hillsides, and (2) very thin topsoil.

In fact the term “topsoil” is, practically speaking, a euphemism. Persistent exfoliation of granitic rocks

in the mountainous areas produces a loose, sandy material that is easily washed

downhill by seasonal rains where, ultimately, it is deposited in the creeks,

washes and gulches. Consequently,

the “soil” that you find on the steep hillsides is exceedingly thin and loose. The essential point is that these terrace

walls were not only constructed to provide flat areas at a point in historical

time, but to also guard against future erosion and sedimentation from the uphill

slopes.

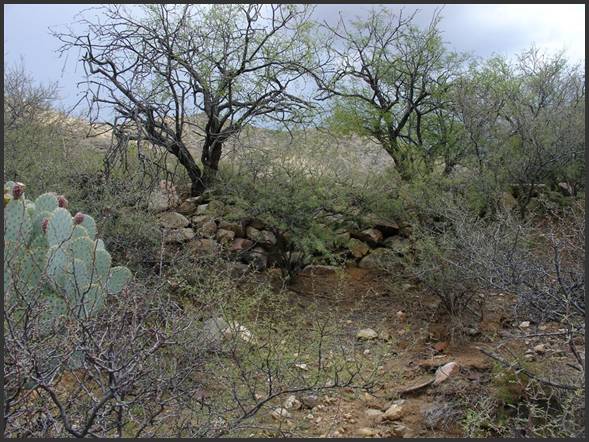

Figure 3, Terrace Wall Covered by

Foliage

Figure 3 shows a terrace wall that is only visible from a close distance. Two search methods can be used to infer

the location of walls of this type.

First, the terrace above this wall

can only be observed from a distance at a

higher elevation. I found this

wall by scanning the terrain from several hundred yards from the west and about

three hundred feet above. The

terraced area was “flat” and relatively free of vegetation – a definitive

indicator of past pioneer activity.

Second, notice the line of mesquite and acacia trees that are located on the

margin of the wall. These trees have prospered from the soil

used to create the terrace. I

believe they have also benefited from the reduced rate of runoff (that is, an

improved rate of moisture absorption).

Whenever you observe a straight line of vegetation in a remote area, you can be

reasonably certain that human activity was involved.

Naturally straight lines are exceedingly rare!

Figure 4, Cemetery Terrace Wall

Figure 4 shows a short section of terrace wall at a large pioneer cemetery. Close observation of the general slope

(from left to right) shows a steady downward incline and it is doubtful there

was any intent to create “flat” ground in the upper portion of the cemetery. Instead, this dry stack was probably

intended to mitigate erosion. There

are two additional terrace walls to the right of this photo that rendered more

level ground for graves. This wall

faces just a few degrees north of west, so it is exposed to considerable sun

light. Notice that these westward-facing rocks

have been “bleached” by a century of exposure.

Figure 5, Cemetery Wall and Wood Post

Figure 5 shows the corner of another dry stack cemetery wall. In my experience, at least, I have found

very few derelict cemeteries that still have wood posts or other structures

(such as grave markers). In this

example you can see a post at the upper right that served as part of a fence

along the southern margin of the cemetery.

The wall in this photo appears to lean into the steep hillside, but it has not

been effective in preventing sedimentation.

The area between this and a lower terrace wall has seen the deposition of

several inches of soil over the decades.

It is usually a straightforward matter to infer the original purpose of a dry

stack wall, as the photos in previous articles will attest. Figure 6 shows one of the terrace walls

at the site known as the “

Figure 6, Terrace Wall at

This dry stack gives the appearance of having been crudely built, and that is

indeed true. Arrastres were known as

‘the poor man’s mill’ and were primarily used to “prove” the value of an ore

vein. This wall lacks the craftsmanship and

aesthetic qualities evidenced in other walls; possibly because there was no

objective beyond the immediate extraction and amalgamation of ore. While the size and weight of these stones

have kept the wall in place, the irregular shape of the rocks has allowed

sediment to flow over and through the wall in the time since it was constructed.

Notice the surface in the foreground of the photo.

It has a reddish cast and is relatively dark. Seasonal rains have steadily washed soil

from the hillside onto the terraces.

More than a century of undisturbed plant growth has been deposited on the site

and mixed into the soil by animals.

The ground slope between the upper and lower walls only became apparent after

the lower terrace was cleared of undergrowth and debris. In fact, the actual base of the wall is

more than twelve inches below the visible surface and there are at least two

more courses of rocks. This photo is

an example of why careful observation is important. If you believe you have you have located

a terrace (that is, with upper and lower dry stack walls), remember that the

purpose was to create a flat area.

If you observe a sloping surface, that is an indicator of sedimentation.

It can be challenging and, at times, frustrating to separate what you see

“today” from what a site would have looked like more than a century ago. Be patient and do not let your first

impression determine your understanding of a pioneer site. There is always more than meets the eye!

What Do These Photos

Tell You?

1.

Good craftsmanship and thoughtful placement of dry stack walls can produce

terraced spaces that will prevent erosion and sedimentation.

2.

Low terrace walls are easily masked by plant growth and can be very difficult to

locate, particularly if they are above your line of sight. However,

3.

If

you can gain advantage with elevation, the flat area behind a terrace wall will

be more easily revealed.

4.

Look for other indicators, such as straight lines of tree growth as an aid to

locating dry stack terraces.

5.

Sedimentation from slopes and soil deposition from flash flooding may mask the

height of many walls.

In Part Five, the final

article of this series, we will examine dry stack rock cabins.

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet Presentation

Version 050109

Copyright © 2009 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this website may be

used

for personal family history purposes, but not for financial profit of

any kind.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer &

Cemetery Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS