HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION

| GHOST TOWNS

| HEADSTONE

MINOTTO

| PICTURES

| ROADS

| JACK SWILLING

| TEN DAY TRAMPS

Internet Presentation

Version 041108

Support APCRP, become a Booster: Click Here

Harquahala Observatory

Photo by: Neal Du Shane 04/07/08

In The Name of Science

Quest for the Solar Constant

In the late 1800’s Dr. Samuel Peirpont Langley believed the

sun caused changes in the climate of the earth. He thought that by measuring

these changes (dubbed the “solar constant”) scientists could predict climate

events. Dr. Charles G. Abbot,

No telescopes were used here. First, a coelostat reflected sunbeams into the observing chamber. A theodolite was then used to measure the sun’s altitude above the horizon; a pyranometer measured heat from the atmosphere around the sun; and two pyrheliometers measured heat from both the sun’s direct rays and scattered rays.

The scientist would then spend many more hours gathering

these measurements and mathematically calculating the data by hand. Reports

were sent to the Smithsonian Institution in

The

Discover Life at the Top

Welcome to the

By 1925 it was decided that another location would be more

suitable due to the severe weather conditions, increased haziness in the air

and difficult access. The station was closed everything was moved to the APO

station on

Step back in time and discover the stories and challenges

that developed from real-life experiences. This site is dedicated to the hardy

and resourceful individuals that lived and worked on

Those Who Answered the Call

The job description must have looked something like this for the people who loved and worked at Harquahala Peak Smithsonian Observatory. Each of those who answered the call contributed something of themselves for us to learn.

The observatory was home to a group of resilient scientist and their assistants who showed amazing ingenuity, resourcefulness, and persistence in performing their duties for the grand experiment.

Although all of these men worked at the observatory during its operation, only a field station manager and a single assistant were assigned to the station at any one time.

THE HARQUAHALA PEAD SMITHSONAN OBSERVATORY

IS DEDICAED TO THE FOLLOWING:

Director of the Astrophysical Observatory: Dr. Charles G. Abbot

Temporary Field Station Manager: Loyal B. Aldrich (September 1920- April 1921)

Permanent Field Station Manager: Alfred E. Moore (April 1921-1935)

ASSISTANTS:

Paul “Peg”

William H. Hoover (1923)

Arthur B. Worthing (1924)

Hugh B. Freeman (1924-1925)

THE OBSERVATORY: THEN AND NOW

The Years of Change

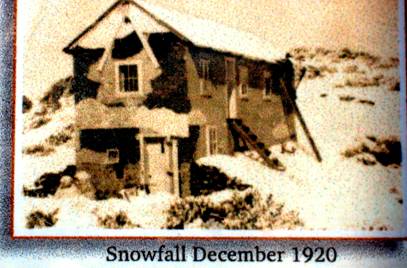

The two-story observatory included both laboratory and living quarters with four rooms on each floor. Almost immediately the building developed large cracks in the south wall and in December 1920 tie rods were added to pull it back into place.

In December 1921, the exterior was covered

with corrugated iron to help protect the fragile adobe walls. Cisterns, porches

and a workshop were also constructed during 1921 and 1922.

In December 1921, the exterior was covered

with corrugated iron to help protect the fragile adobe walls. Cisterns, porches

and a workshop were also constructed during 1921 and 1922.

After the site was abandoned in 1925, the workshop and porches collapsed and the north cistern was removed so a wildlife catchment could be built. By 1975, when the observatory was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the building was in danger of collapsing.

Today, the building is stabilized and supported by wood braces throughout the interior, but is not safe enough to allow visitors.

Harquahala Observatory April 7, 2008

Photo by: Neal Du Shane

SCIENCE OR SURVIVAL?

Satisfying the Basic Needs.

Food – Scientists hauled food, water, supplies and equipment up the mountain weekly on pack animals. Their closest neighbor, William Ellison, helped by providing the use of his animals, assisting with pack trail maintenance, and sharing his fresh homegrown vegetables.

Water – The closest water source was located

over a mile away and 1,000 feel below the summit. Many times the scientist had

to haul it up themselves! Cisterns were soon constructed to collect rain water

which they called the “

Shelter – The building was designed to serve the needs of the observers and the equipment. The upper level served as kitchen, office, and sleeping quarters and the lower level housed the delicate equipment. Comforts included a wood burning stove, a Kelvinator refrigerator and a shower bath in the workshop.

Harquahala Observatory Looking to the south

Photo by: Neal Du Shane 4/07/08

Amenities: Harquahala Style

Chella’s World

Who would bring a new bride to a remote place like the Harquahala Peak Smithsonian Observatory? Newlywed Alfred Moore! Alfred, the observatory field station manager, brought his new bride, Chella, to live on top of the mountain from 1921-1925.

It was Chella’s presence that brought most of the amenities to the station. Alfred wanted to make things as “cozy as possible for her”. Upon arrival he set to work building amenities like a shower, metal siding, porches, a water collection system, and a workshop. His most ambitious projects included the installation of a Kelvinator refrigerator, and wireless radio receiver and a telephone.

“Mr. and Mrs. Moore arrived on scheduled time May 11 and brought a lot of improvements with them. They are both jolly, agreeable people, just what a place like this needs. The kitchen has been quite a change since the arrival of Mrs. Linoleum on the floor, curtains on the windows, oil cloth on the shelves and a real table cloth on the dining table . . . “ Frederick A Greely Jun 8, 1921

Croquet Anyone? One of the few amenities that survived and is still visible a croquet court! They grew “tired of playing horseshoes for out-of-door exercise” so Chella’s brother gave her a croquet set for her birthday in 1921. Just imagine playing croquet here with Chella and Alfred in 1922 with this beautiful view around you.

It’s All A Matter of Communication

From Heliographs to Microwaves

How did the scientist communicate with the outside world? Initially, they sent messages via heliograph which required reflecting Morse code signals on mirrors. This technique was very time consuming; at nighttime and on cloudy days, messages were only possible with bright light. There had to be a better way . . .

Wireless radio was tried next to send telegrams to the local

town of

The telephone was the answer but required the installation of large amounts of wire over very rough terrain. Wire was laid by the scientist and Mr. Ellison, across large boulders and saguaros down the north-slope to the garage. The long awaited telephone finally be came reality.

“This

morning it was rather cloudy but the sun shone enough so we could signal an

order to Wenden and they are going to bring up our

provisions and mail tomorrow. We use mirrors in the daytime and lights at night

so we can signal about any time of day.” Frederick A. Greeley December 19,

1920.

“This

morning it was rather cloudy but the sun shone enough so we could signal an

order to Wenden and they are going to bring up our

provisions and mail tomorrow. We use mirrors in the daytime and lights at night

so we can signal about any time of day.” Frederick A. Greeley December 19,

1920.

Today, the summit remains essential for communications.

Modern microwave facilities were build in 1983 by the Central Arizona Project

(CAP) to direct water flow in the CAP canals located throughout central

“Alfred and I are going to run the phone line from here to the garage . . . going down over the mountain we are going to use big boulders. Drill holes in them and cement inch rods in the holes. Further down where there are no suitable boulders we will use giant cactuses as poles.” Frederick A Greeley October 15, 1922

HARQUAHALA PACK TRAIL

The Harquahala Pack Trail was used to access and transport

supplies and equipment to the Harquahala Peak Observatory. After the

observatory was abandoned in 1925, this historic trail continued to serve

miners and ranchers attempting to wrest a living from rugged and isolated

Trail Tips

The trail is 5.4 miles long and extremely steep. From the

summit of the

The trail is located almost entirely in the 22,800 acre Harquahala Mountains Wilderness. Please remember that the desert is fragile and to minimize your impact to this valuable wilderness resource.

Dogs are required to be leashed and under control.

Hike Safely

Even in winter, the desert sun can be intense! Rest often; wear sunscreen, sunglasses, and a hat; and drink plenty of water.

You may encounter rattlesnakes or other poisonous creatures. Watch for them and be careful where you put your hands and feet.

Do not harass reptiles – most bites result from people playing with, collecting, or attempting to kill them.

Carry a comb or small pliers to remove cactus spines.

Transcribed by: Neal Du Shane 4/11/08

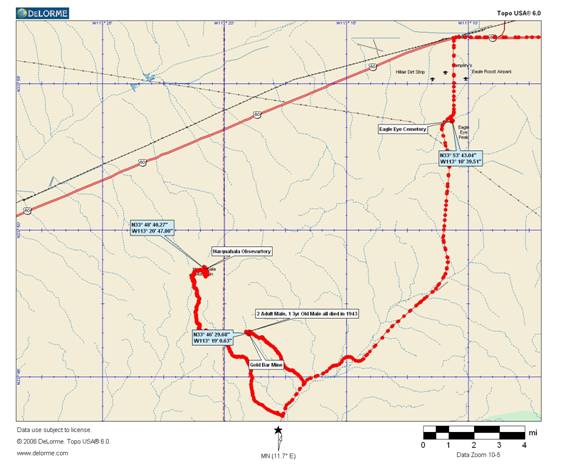

ROAD TO HARQUAHALA OBSERVATORY

The road to the top is approximately 10.8 miles of rough gravel road once you leave the blacktop road. Elevation gain in that distance is about 3,360’. Kevin Hart and I made it to the top in 50 minutes with his Wrangler Jeep. The road is definitely a four wheel drive road moderately difficult on April 7, 2008 when we went to the top. However weather conditions and maintenance would change this rating to very difficult in one storm. Please be advised and proceed with caution. The day we were there is was extremely cold with a high wind; take a jacket and warm clothing just in case you encounter similar conditions.

Route from Agila, AZ. Stay on

Map by: Neal Du Shane 4/7/08

Internet Presentation

Version 041108

WebMaster: Neal Du Shane

Copyright ©2003-2008 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved.

Information contained within this website may be used

for personal family history purposes, but not for financial profit of any

kind.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer &

Cemetery Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION

| GHOST TOWNS

| HEADSTONE

MINOTTO

| PICTURES

| ROADS

| JACK SWILLING

| TEN DAY TRAMPS