American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet

Presentation

Version 052409

SUPPORT APCRP

BECOME A BOOSTER

Researching a Depression Era Mine

By: Allan Hall – APCRP Certified

– Historian – Author

Photographs by: Author

Introduction

No one can

say with certainty how many adits and shafts have been dug in Arizona’s mining

districts in historic times. Estimates vary considerably – even between state

and federal agencies – but could range as high as 100,000 hard rock mine

entrances. The vast majority fall into two broad categories: “past producers” and “prospects” and nearly

all of them are now abandoned. The steady decline in gold and silver production

during the 1920’s and early 1930’s led to the closing of many mines. Settlements

were dismantled, or simply abandoned, as people moved

on to seek their livelihood elsewhere.

After the

earlier pioneer period, another wave of migration occurred following the

economic collapse and ensuing depression of the 1930’s. These were jobless and

homeless men and families. For some of them, their attraction to the mining

districts was the based upon the hope that a few ounces of gold each month

could keep them fed. For others, a lode claim provided a cheap way to live on

the land – whether there was any ore or not.1

Within a one

mile radius of Morgan Butte peak2

there are more than sixteen mine shafts and adits. If you extend your search

area to a radius of barely two and a half miles, there are several dozens of

old mines and associated settlements. Although some of them date to the late

1800’s (and a few were good producers), the majority were established in the

era that extended from the early 1900’s to the Great Depression of the 1930’s. Unfortunately,

the geology in this locale virtually guaranteed that most mines would turn out

to be a disappointment. While there were

many promising signs of ore, nature conspired to place much of it in small

pockets and seams. What might appear to be high grade ore in an exposed vein could

abruptly end after only fifty feet. More frequently, the vein contained low

grade ore that could not offset the cost of extraction and processing for a

small time operator.

Without

investors, the only way to make a go of it at a low producing mine was to have

little or no capital burden. This article will focus on a mine and small

settlement near Morgan Butte that fits this broad characterization: It was a

low producer, there was no mill or heavy equipment and, from appearances, there

was virtually no operating overhead. Moreover, the features at this mine

suggest that it worked during the 1930’s. By that time, most of the successful

mines in the area had already run their course.

A

Depression Era Mine

The subject of

this article is a mine located about .75 miles NNE of Morgan Butte (roughly 36

degrees east of true north from the peak3).

This area is literally blanketed with old (closed) and active lode mining

claims and it includes a patchwork of patented land that is now deeded to

modern day ranchers and investors.

We have

discussed on many previous occasions the use of arrastres. They were the “poor

man’s mill” – a way to cheaply pulverize silver or gold bearing rock. The rate of processing would be limited to only

a few hundred pounds of rock over a period of several days. Typically, an

arrastre would add mercury to the ore charge to produce an amalgam. The older “Mexican”

arrastres around Wickenburg were constructed using shaped stone in the walls

and floor and did not use mortar or cement. Notice the more modern style of the

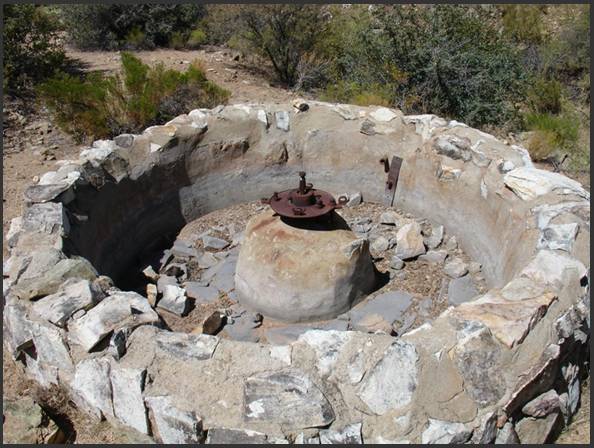

arrastre at this site:

Figure 1, Depression Era Arrastre

Figure 1 shows

an arrastre that is quite tall by normal standards, but which has a relatively

narrow inner diameter. It was constructed with cement and boulders to a height

of more than three feet. The area surrounding the arrastre is still quite flat

and afforded ample space for a mule to pull the drag stone that crushed the ore

charge.

Arrastres of

this type can generally be classified as post-1900. In this example however, I

believe it dates to the 1930’s, but not more than one decade earlier. More on that subject later.

Figure 2, Top View of Arrastre

Figure 2 shows

an inside view of the arrastre. The interior wall was fully encased with cement

and the metal center post is, if anything, over engineered. The floor was built

using stonework in the traditional manner. This is probably because a cement

floor could not have withstood the abrasive effects of the drag-stone. The

width of the floor was wide enough to accommodate a single drag stone –

suggesting that only two or three hundred pounds of ore was processed during

each cycle.

There are two

particularly interesting features in the interior of the arrastre.

First, notice the two drain pipes to the right of center. The lower pipe is in

a metal plate, while the upper pipe protrudes through the wall to the left. Second,

notice the abrasion and water marks on the center column and inner wall.

There were

several steps involved in the pulverizing and amalgamation process using an

arrastre. Once the ore charge had been

thoroughly reduced to a fine sandy texture, water would be added to produce a

fluid, muddy consistency. At that point, mercury would be added and the

drag-stone operation might continue for another few days. This was a critical point in the mixing of

the ore/sand/mercury. The objective was to continually mix the components so

that amalgamation (a chemical bonding between the ore and mercury) would occur.

Finally, more

water would be added (that is, to the higher pipe) to produce a ‘soupy’ texture

while the mule would continue to pull the drag stone, but at a slower rate. This

would permit the amalgam to slowly settle to the bottom of the arrastre. The

water would then be drained away and the waste material would be scooped out. The

ore (gold or silver) would have settled on the floor, where it could be removed

and separated from the mercury.

Figure 3, Drag Stone with Cable

Further

evidence that this arrastre dates to the early decades of the 1900’s is

provided in Figure 3. Notice that this

drag stone has a steel cable inserted on the top. Older, ‘Mexican’ arrastres used drag stones

that typically weighed more than 200 pounds and featured a bent iron rod

protruding from the top. I have never

seen an ‘old’ arrastre (one that can be dated to the 1800’s) that used steel

cable. Aside from the use of this more

modern feature, the drag stone does not weigh much more than 100 pounds.

Figure 4, Another

Drag Stone with Cable

Figure 4

shows another drag stone at the arrastre. Like the previous one, it used a

steel cable to connect to the rotating arm that was pulled by a mule or horse. In

this case, the stone is nearly the width of the drag area inside the arrastre. Notice that five edge faces of this stone and the

bottom have been worn smooth from use. There are relatively few drag stones at

this site (only four that I have confirmed). Considering the relatively small

capacity of the arrastre and the nature of the mine, I believe it was not used

continuously. Otherwise, there would be more drag stones.

There are two

unanswered questions in the views of the arrastre. What was the source of water

and, importantly, did this arrastre use mercury for amalgamation?

Figure 5, Wet Panning Site above Arrastre

Approximately

100 yards above the arrastre there is a rather ingenious site that was used for

separating ore from pulverized waste. Figure 5 shows a rock and cement

structure that features a high wall, a ledge, two troughs and a drainage sluice

(center of photo). This is the functional equivalent of a “panning” site that

would have used water motion to separate the heavier gold ore from the lighter

waste material. The design of this structure suggests to me that the arrastre

did not rely upon mercury for amalgamation. In other words, the arrastre

pulverized the ore bearing rocks and the “panning” site completed the

separation of ore from waster material.

Another fifty

feet or so beyond this structure there is a spring and well (perhaps more

properly described as a cistern) that collected water for the arrastre and the

washing/panning structure. See Figure 6.

Figure 6, Well/Cistern

Today, it

serves as an occasional source of water for cattle that graze this section of

land. The rancher has protected the opening to limit the inflow of debris. Not

clearly visible, but importantly present, there is a metal ore car rail on the left

side of the well opening. A feature such as this suggests that at least one of

the three adits at this mine may have had rail tracks and an ore car. I have

found no other rails outside the mine entrances, but tracks may remain in the

interior of one or more adits.

When I examined the well site, the water level

was several feet deep and was clear. Decadal drought conditions have reduced

the flow of water, but would still provide ample volume via gravity feed to the

arrastre, panning area and modern water trough. There are old metal and modern

PCV pipes running down the gulch that show the original and modern uses of the

well. Seasonal rains certainly contribute to the water level and probably

produce some rather significant runoff in this steep and narrow gulch.

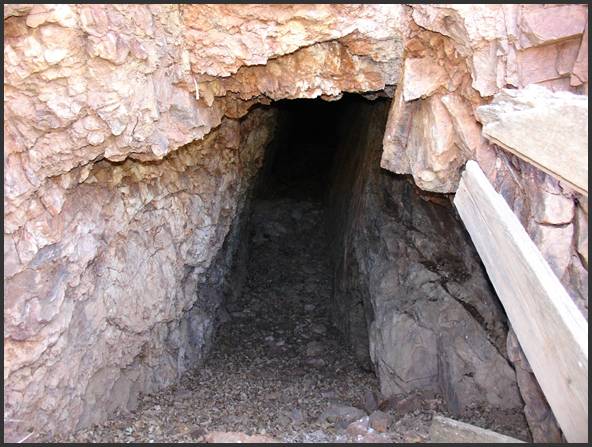

Figure 7, Upper Adit

This mine

certainly qualified as a “hard rock” operation.

As shown in Figure 7, the upper adit (one of three entrances) was dug

and blasted into a very solid face of the mountain. The adit gives an appearance of a gentle slope

in a westerly direction. The gangue pile in front of the adit indicates that a sizable

quantity of rock was removed to reach the primary ore vein. I have not entered

this adit and I do not suggest that you do, either - it may serve as habitat for

snakes and other wildlife. Furthermore, it is not possible to assess the

condition of the adit beyond the first few feet. The sizable boulders at the

entrance show that rock has sloughed off the wall above the mine.

Figure 8, Second Adit

Figure 8

shows the second adit, west of the one in Figure 7. Both adits

probably contained narrow veins of ore that were extracted during the mining

process. I found no evidence of copper in the first dump and it is likely that

this mine was chasing a vein of gold. This adit is

characteristic of the rock formations commonly found in this area. The adit

literally follows the slope and angle of the vein. The height and width of the

adit was very conservative - that is, you could enter without stooping, and the

width at the entrance is not more than thirty inches.

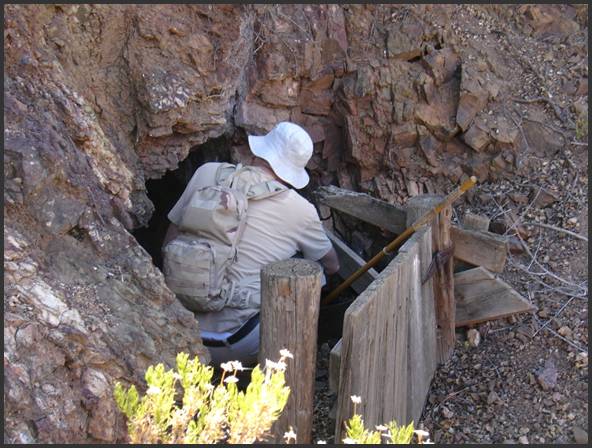

Figure 9, Entrance to Adit 3

Figure 9

shows the entrance to the third adit, which is farther west of Figure 8. This

is the only gated entrance at the mine site. It is again apparent that the

entrance is quite small. The presence of the gate may indicate that a winze

(vertical shaft connecting different levels of adits) lies beyond the entrance.

Although one of my hiking partners is examining the entrance, we did not go

beyond this opening. There is a rather sizable dump to the right of this photo

that contains a few hundred tons of waste rock.

Notice that

two of these adits contain structures built with wood posts, boards and planks.

They appear to be in generally good condition. Each adit

is protected by steep (nearly vertical) walls in this gulch, which has probably

protected the wood from rapid decay.

Initial

Assessment

An evaluation

of the first nine photos suggests the following:

1. The manner of construction of the

arrastre clearly indicates the use of more modern materials than are found at

the older, traditional “Mexican” arrastres.

2. Although the wall was unusually high,

the capacity for pulverizing ore was quite limited due to the narrow inner

dimensions.

3. Steel cables were not used for pulling

drag rocks in the 1800’s or at any earlier point in time.3

4. There is no convincing evidence that

mercury was used at the arrastre. Instead, it is likely that the pulverized ore

was taken to the “panning” site shown in Figure 5 where it could be gently

washed to separate gold from the waste material.

5. The adits at this mine were quite

small. The development of this mine shows considerable economy in effort and

expense. In other words, the adits were “just wide enough” to get the job done.

6. In comparison to mines that were high

producers of ore, the dumps at this site are not very large. This correlates

with the small dimensions of the adits, but also suggests that the tunnels and

drifts were not extensive. The “pay streak” at this mine, such as it was, must

have been very narrow.

7. Given the low-budget nature of this

site, the recovery of a few ounces of gold each month could have kept this

operation going.

Living

Conditions

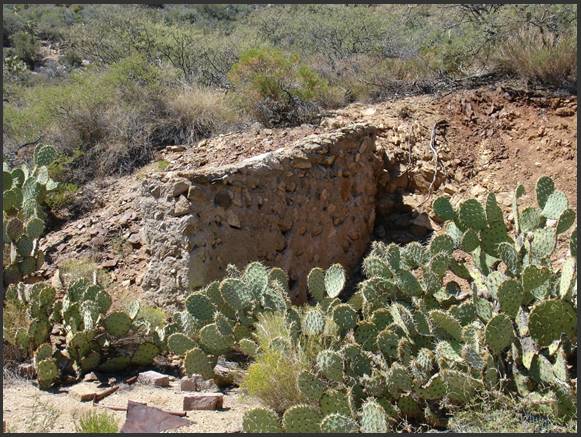

Finally,

let’s examine the small settlement area near the mine. Figure 10 shows the only

wall at this site. It is not a dry stack and, importantly, it is not adobe. Instead,

this wall was built using a combination of mortar and local rock. The

coloration on the right face indicates that dirt was added to the mixture,

possibly as an “extender.”

Figure 10, Settlement Wall

The wall is

actually pretty solid and shows no signs of weathering or erosion. Notice also there are three crude bricks in

the lower foreground near the cactus. I have not been able to piece together

the surface features, but the bricks might have been used in a fire pit or some

type of improvised oven. Because there are no other walls in the settlement

area, it is possible this structure may have served as a “lean to.”

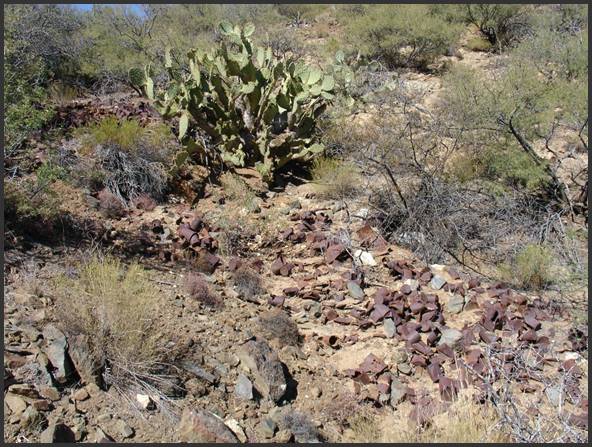

Figure 11, Debris Field at Settlement

Figure 11

shows a small portion of the trash dump at the mine settlement, which is uphill

and out of view to the left. The trash extends left and downhill from this location

for another twenty yards. Considering the modest nature of the mine, this is

one of the largest debris fields I have encountered.

Other

features of the settlement include the remains of a collapsed outdoor privy, a

burned out metal drum that was lined with cement, and a few boards and pieces

of pipe. The metal drum may have been an

open air fireplace. There is no evidence that heavy machinery or electrical generators

operated at the mine. In other words, the work and living conditions were about

as primitive as you could imagine.

Historical

Context

I do not know

when this mine was established or how long it operated. Surface features

strongly point to an occupation no earlier than the 1920’s, but it was more

likely established in the 1930’s. The Great Depression was a brutal time for

everyone – no jobs, lost homes and little hope. There are anecdotal records

that up to 20,000 people lived in the mining districts east of Wickenburg

during that time. This unnamed site is probably one of the locations where hopeful

people tried to scratch out a meager living.

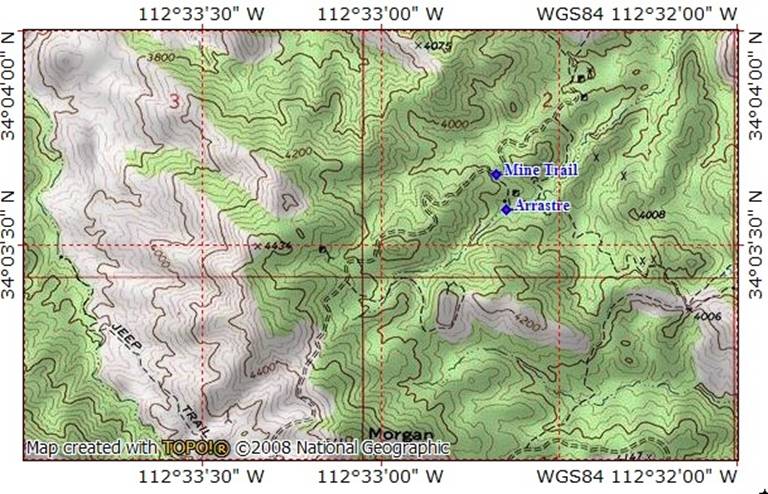

How

to Get There

The route to

this mine is provided in the attached topo map. I should point out that the old

mine trail that crosses the northern flank of Morgan Butte is particularly

rough. It absolutely requires high

clearance 4WD or ATV type vehicles. The trail over Morgan Butte has not been

maintained for many decades and is bare granite with deep runoff trenches in

many locations. You should consider taking a back up vehicle if you make this

outing. The trail continues east into a basin and passes on the southern slope

of Table Mountain. It then drops into another basin before taking you to Roberts

Camp near the upper end of Buckskin Canyon. As rough as the Morgan Butte

segment of the trail can be, the portion that traverses Table Mountain is even

worse.

1.

From

the Wickenburg Rodeo Grounds, proceed east on Constellation Road.

2.

Turn

right onto Buckhorn Road at GPS N 34o 02’

32” by W 112o 36’ 46”.

3.

Turn

left at GPS N 34o 02’ 55” by W 112o

33’ 24”. This turnoff is easy to

miss. It is in the bottom of Slim Jim

Creek (upper end). There have been several washouts in the past few years and

the trail may not be obvious. Following

the trail, you will pass a corral and water tank on your right. Remain on the trail. It will lead you out of Slim Jim Creek.

4.

Bear

right at a mine gate and continue up the trail as it climbs the northern flank

of Morgan Butte in an easterly direction.

5.

You

will come to a livestock gate shortly after cresting the top of the trail on

Morgan Butte. This gate should always be closed.

6.

Continue

down the trail until you arrive at GPS N 34o

03’ 40” by W 112o 32’ 41”.

You have the option of either parking in this saddle or driving down the

trail to the mine settlement. Caution –

there are a lot of old nails on this portion of the trail. You might want to

check it out on foot before choosing to drive to the settlement and arrastre.

7.

The

arrastre is located at the bottom of the trail (south of the gulch) at GPS N 34o 03’ 35” by W 112o 32’ 38”.

8.

Follow

the gulch uphill (west) to locate the adits, well and panning area. See Reference #3 for the location of the

first adit.

Before

You Go

As previously

stated, this area is a combination of private, deeded land and BLM/State Trust

land. If you meet someone, they may very well be a land owner. Always be

courteous and respectful. Ranchers have grazing leases in the area and have a

vital economic interest in the well-being of their cattle.

Bring plenty

of water and energy snacks for this outing. Be aware of weather conditions and

high temperatures. The gulch and hillsides leading to the adits are covered

with thick foliage. Dress appropriately.

Always let

someone know where you will be and when you plan to return.

References:

1.

There

are quite a number of mine shafts in the area east of Wickenburg that are only eight

to 15 feet in depth. In most cases,

there is little or no evidence of useful results. Many of these were “squatter”

prospects. Others gave only the appearance of being a legitimate mining

operation. Ranchers in this area have told me there were several thousand

people living in the open desert and at old settlements during the Depression.

2.

USGS

Morgan Butte Quadrangle map. Morgan Butte is located at N 34o 03’

03” by W 112o 33’ 06” (WGS84). See sections 1-4 and 9-12 as the

primary reference area in this article.

3.

Here

are two sets of GPS coordinates. The first is for one of the adits and the

second set is for the arrastre: Upper

adit – N 34o 03’ 24” by W 112o 32’ 49”. Arrastre – N 34o 03’ 35” by W 112o

32’ 38”.

4.

Steel

cable (also known as wire rope) was first developed in the 1830’s by a German

mining engineer named Wilhelm Albert and came into use in the late nineteenth

century for hoisting heavy loads in deep mines. The cables shown in this

article do not match the type of cable used in the latter portion of the 1800’s.

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet

Presentation

Version 052409

SUPPORT APCRP

BECOME A BOOSTER

WebMaster: Neal Du Shane

Copyright

© 2009 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this

website may be used

for personal family history purposes, but not for financial profit of any kind.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer & Cemetery

Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS